‘We’re not far from wolves.’

– Deleuze and Guattari, ‘1914: One or Several Wolves?’

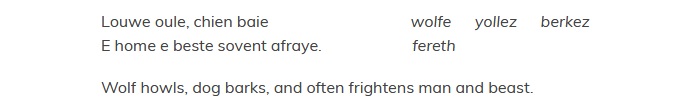

Human-canine relationships are some of the most conceptually disordered and uncertain of interspecies relationships, precisely because the history of domestication is so long and so complex. The type of canine perspective offered by contemporary writers such as Donna Haraway and George Monbiot may have its toes dipped in a modern understanding of how humans, dogs, and wolves cohabit shared environments in the modern world, but canine perspective is not new, and has its roots far deeper in historical thought. In the thirteenth century, a medieval English writer, Walter of Bibbesworth, enjoined his readers to consider this very complexity through a depiction of the sounds of wolves and dogs in a multilingual treatise on how to run an estate, written in French with glosses in English:

Louwe oule, chein baie. Set side by side, wolf and dog are divided by a caesura, their biological and social differences and similarities reinforced through poetic proximity. At the same time, they are united by a semantic field that emphasises the fear that howling and barking cause to other species, ‘home e beste’, man and beast. Glossed by the author in English as wolfe yollez and [dog] berkez, the sounds of these canines carry across lines, and cross over languages, into the ears and minds of the reader or listener. But what further effect do these lines have on an audience, whether medieval or modern? And, in line with a critical landscape that forces us to consider the implications of depicting and interpreting animals through different mediums of expression, what kind of response to the animals represented is anticipated by this medieval text?

Wolves were perhaps best identified and rendered present by the sounds that they made.

In order to tackle these questions, it is necessary to draw a picture of the kinds of associations and experiences with which wolves were associated in England during this period. As Oliver Rackham explains in The History of the Countryside, records of wolves in medieval England seem generally to be confined to the Welsh Border counties and the northern regions of Britain, with little record surviving from the Anglo-Saxon period:

The one exception is a bounty of 5s. paid for a wolf caught at Freemantle (Surrey) in 1212; this quite large sum cannot often have been paid out. Evidence of wolves continues up to 1281, when Edward I exterminated them. He employed Peter Corbet ‘to take and destroy all the wolves he can find in … Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, and Staffordshire.’

In medieval England at least, wolves then all but disappear from historical record, leaving their traces in fiction and the medieval imagination, haunted by werewolves and cross-species encounters. The call by Edward I to eradicate wolves from the countryside of England demonstrates that the intended destruction, and therefore the lingering presence, of these animals was a political concern, but it also suggests that wolves by this time were being pushed back to England’s borders, and away from centres of increasing urbanisation such as London. The Bibbesworth estate, parts of which exist to the present day, was in Hertfordshire, just north of London, so this seems an unlikely location in which to encounter wolves at the time the text was written. Instead, the contextual information concerning the presence and absence of wolves during thirteenth century would place the treatise well into the realm of fiction, in turn aligning it with other medieval literary works where imaginary wolves provide encounters with the strange or unknown.

The wolves of the treatise, however, are not entirely fictional constructs. Whilst werewolves were especially renowned during the Middle Ages for their transformational capacities, wolves themselves were perhaps best identified and rendered present by the sounds that they made, as well as by the traces of their physical presence on the land. The medieval French verb ouler, more commonly written huler or heuler, emulates the sounds of wolves howling when spoken aloud by a human reader, as does the Middle English gloss yollez, from the verb houlen. The context of the treatise in rural medieval England emphasises absence as a key factor in humans imagining the presence of wolves, but the sounds depicted through human language in the text indicate a close proximity or assimilation of the sounds of the animals into human discourse. The text is an encounter between human and textual animal: a form of contact zone that balances absence and presence — extinction and proximity — in order to create a web of affiliation between human and animal that works constructively to teach or demonstrate the sounds that animals make. It provides a way of interpreting the animal world through the medium of human language. But sound also spills off the page and out of the human reader’s mouth, as the desire for imitation and sonorous play fuel a desire to become closer to the animal, even if, or perhaps because, that animal’s real presence in the landscape is a dwindling one, settling into the recesses of memory.

For a modern reader, the howling of wolves is an indication of an anxiety about their disappearance.

One of the questions that arises from this discussion concerns the anxieties that the text presents about response to the presence or absence of wolves on the page and in the social and cultural context of the period. Today, in light of historical perspective and ecocritical discourses on animal extinctions and reintroductions into what might be described as natural or wild spaces, the phrases ‘louwe oule’ and ‘wolfe yollez’ create a certain nostalgia and unease for a reader aware of the increasingly harsh effects of the eradication of species because of human conduct. From a present-day perspective, the extinction of wolves from the British Isles in the Middle Ages represents not only the loss of life and of habitat that we now associate with these animals, but also the loss of the plural complexity of meanings that accompanies the extinction of animal and non-human life. In H is for Hawk, Helen MacDonald mourns the loss of meaning associated with endangered or extinct species:

I think of what wild animals are in our imaginations. And how they are disappearing — not just from the wild, but from people’s everyday lives, replaced by images of themselves in print and on screen. The rarer they get, the fewer meanings animals can have. Eventually rarity is all they are made of.

In a very similar way, for a modern reader, the howling of wolves in the treatise is an indication of an anxiety about the disappearance of wolves, and of the loss of a physical and imaginative contact zone between wolves and humans. This zone is partially carried through the continuing connections between humans and other canines, such as dogs; relationships that may have in some ways replaced the encounters between wolves and humans in the early Middle Ages, even if many of these were based on fear, prejudice, and violence, rather than on companionship.

In the thirteenth century, wolves were animals that clearly gave rise to heavy political implications, both at court and in the imagination of readers of texts like Bibbesworth’s treatise. They triggered a host of different anxieties, including socioeconomic pressures (on farmers in particular), deception, and the fear of being eaten. As Karl Steel notes in How to Make a Human, despite the culling of wolves by professional wolf-hunters known as luparii, wolves ‘were sometimes […] introduced into game parks, not to cull herbivores, but to be hunted. The degradation of wolves’ status from feared predator to poacher to prey — and, at that, inedible prey — suggests that such hunts functioned primarily to reaffirm the human, and particularly the elite, position as masters of violence.’

These themes chime with a hunting relationship between human, hunter, and dog expressed in Bibbesworth’s treatise by the fear induced in both man and beast by the howling of wolves and the barking of dogs. Although man is present as a hunter in thirteenth-century England as well as in this text, he also experiences fear, and similar practices of power and fear are played out in the animal kingdom in parallel to the human-hunter scenario. The broad zone of contact between humans and animals that is created by the play of language in the text and the references to multiple ways of living and communicating with animals such as wolves brings to light the similarities between human and non-human behavior, albeit described and interpreted from a human perspective in the poem.

The text as a contact zone between human and canine, and reminds us of the need to teach and practice acts of care.

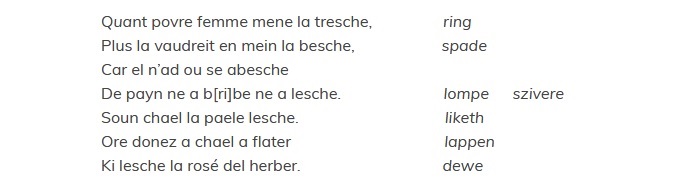

The resonances that this passage on wolves creates with the themes of extinction and loss are in some ways juxtaposed with the portrayal of dogs later in the same section. Following a jumbled discussion on hens, sheep, spices, sleep, and the practice of preaching, Bibbesworth introduces the image of a poor and hungry woman and her dog, to whom the narrator enjoins the reader to give something to drink:

When the poor wife leads a ring-dance, it would have been better had she taken a spade in her hand, because she has nothing to feed herself, not a piece or a slice of bread. Her pup licks the pan. So give the pup, which is licking the dew off the roses in the meadow, something to drink.

Ore donez a chael a flater. So give the pup something to drink. We end full circle, back with Haraway and When Species Meet. Haraway reminds us that ‘ways of living and dying matter’ and raises a tantalising question:

which historically situated practices of multispecies living and dying should flourish? […] Respect is respecere—looking back, holding in regard, understanding that meeting the look of the other is a condition of having to face oneself.

In the treatise, after the violence of the hunt and the babel of the animal noises, Bibbesworth pulls the reader’s attention away from noise and sound and onto a depiction of a dog who licks the pan of his poor human and the dew off the roses in the garden. This is a scene of shared poverty, but also of tenderness and beauty, and a potential call from the narrator — perhaps even from Bibbesworth himself — to an act of kindness; an act which defines the relationships between the human reader and the pup of the text. This is one example of a historical mode of interaction between human and canine that is based on mutual respect and understanding. Depicted as it is through poetry, the text brings this interaction to life by the injunction ‘Ore donez’ (Now give) that enjoins the reader to act in kindness like the woman who shares water and sustenance with the puppy. Under the main premise of the treatise, which is to instruct children in the language used for running a thirteenth-century estate, the invitation is to take action against the poverty and suffering experienced by animals. It opens up intriguing possibilities for reading the historical text as a contact zone between human and canine, and reminds us of the need to teach and practice acts of care and nurture in contact with a world populated by non-human beings; beings that are pushed ever further from our hands, our ears, and our minds.

Part of The Learned Pig’s Wolf Crossing editorial season, spring/summer 2017.

Cover image: Jean de Mandeville, Le Livre des merveilles du monde, c.1357-1371