The history of concrete poetry charts a path from utopia to dystopia. You could say that there’s a secret history of the second half of the twentieth century embedded in this little movement, one that parallels larger changes across cultural output. By the late 1970s, when concrete poetry collapses into a smouldering heap, few could have foreseen that it would arise as a digital phoenix in the computer age, presciently predicting the ways we would interact with language in the twenty-first century.

Sitting on my desk is a catalogue that was made to mark the half-century anniversary of the founding of the seminal Brazilian concrete poets known as the Noigandres group, consisting of the brothers Haroldo and Augusto de Campos, along with a fellow student named Décio Pignatari. They set out to change literature by creating a universal picture language, a poetry that could be read by all, regardless of what language they spoke. Letters would double as carriers of semantic content and as powerful visual elements in their own right. Often the poems – written in just about every language imaginable – came with a key so that, even if you didn’t know, for example, Japanese, you could get the gist of what a handful of kanji compellingly strewn across a page added up to.

Delightful to the eye, and political in its intent, their agenda was nothing short of revolutionary: to create a visual Esperanto that would ultimately dissolve linguistic – and thereby political – barriers between nations. The movement, drawing from Poundian imagism and Joycean wordplay, dovetailed with the twentieth century’s drive toward condensed languages as expressed in advertising slogans, logos and signage. By shedding all vestiges of historical connotation – including metaphor, lineation, spontaneous composition and organic form – concrete poetry planted itself firmly within the grand flow of modernism. These poems, to paraphrase Ezra Pound (a major influence for the group through his use and theories of ideograms), sought to literally ‘make it new’.

By the 1980s, the concrete poetry movement had pretty much collapsed, subsumed by larger trends, such as mail art, where one swapped concrete poems as readily as wobbly cassettes, postage-stamp-sized paintings, tabletop sculptures and folded-up posters. Concurrently, small press culture arose with its vast horizontal networks and voluminous production. Concrete poetry became a mere trickle of the torrent it once was, rendered nearly invisible as a minor note in a greatly expanded field.

There’s a theory that the moment something verges on obsolescence, it’s also on the cusp of revival, ready to reincarnate itself into new forms and uses. It’s been noted, for example, that when the horse was rendered obsolete as a mode of transportation, it found a new role in recreation. Or, in a cellular age, that the availability of digital music on the smartphone or iPod has seen a steady rise in the sale of vinyl, now fetishised for its physicality. While we used to get our information from magazines, today they resemble overproduced coffee-table books, more to be browsed than to be read.

And once concrete poetry had run its course, it too found a new and unexpected role in the digital world. In fact, many of concrete poetry’s ideas about language’s materiality have ended up being mirrored in our computational systems and processes. When our cursors interact with language, they do so in a physical way. Take, for instance, the computer’s simple cutand- paste function. When we highlight a word (note the word ‘highlight’) by moving our cursor over it and pressing down, we are literally picking up that word and moving it elsewhere. When we click on a link, we literally press down on a word. When, in the analogue age, did we ever press down on words?

Concrete poems being written in the twenty-first century have all been strained through the digital – and in some ways, have reacted to it; call it post-digital concretism. Even in cases where the poems might look similar to what was done in the last century, there’s something different about them that responds to the digital in the ways they’re produced, constructed, or distributed. Concrete poetry in the twenty-first century always winks at its twentieth-century precursors.

While visual artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger have worked with words for decades, a large number of young gallery-based artists are self-identifying not as ‘text artists’ but as ‘visual poets’. In the same way that the art world has recently reimagined traditional, stagnant art forms such as dance and performance art, poetry is now receiving a similar treatment; last year’s 89plus exhibition and workshop in Zurich, Poetry Will Be Made By All!, found dozens of poets under the age of 25 creating visual poetry in the gallery space, plastering the walls with word decals, aggressively pumping out poster-sized broadsides, doing daily webcast readings, tapping out smartphone poetry and publishing 1,000 print-on-demand books of poetry by young poets from around the world.

Concrete poetry’s great gift was to demonstrate the multidimensionality of language, showing us that words are more than just words. What seemed like a marginal and boutique pursuit in the twentieth century has turned out to be prophetic in the twenty-first. Language is exploding around us in ways that the founders of the movement could never have predicted, but would be delighted by. Like Willem de Kooning’s famous statement, ‘history doesn’t influence me. I influence it’, it’s taken the web to make us see just how prescient concrete poetics was in predicting its own lively reincarnation in the twenty-first century.

This is an edited extract from Kenneth Goldsmith’s introduction to The New Concrete: Visual Poetry in the 21st Century (Hayward Publishing, London, 2015) £30

Image credits (top to bottom):

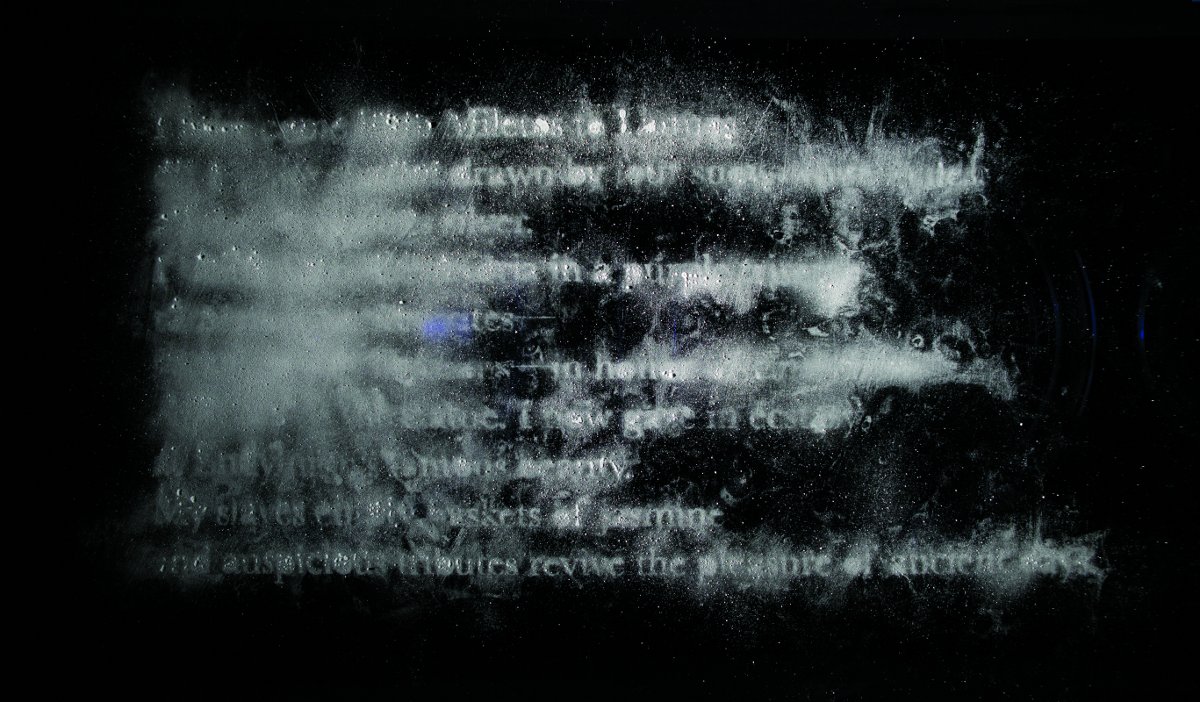

1. Rick Myers, An Excavation/A Reading (Before the Statue of Endymion), 2014. © the artist. Translation courtesy of Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard

2. Ilse Garnier, Auriga – from L’année les jardins flottants de la somme, 2009. © and courtesy the artist

3. Ilse Garnier, Orion – from L’année les jardins flottants de la somme, 2009. © and courtesy the artist

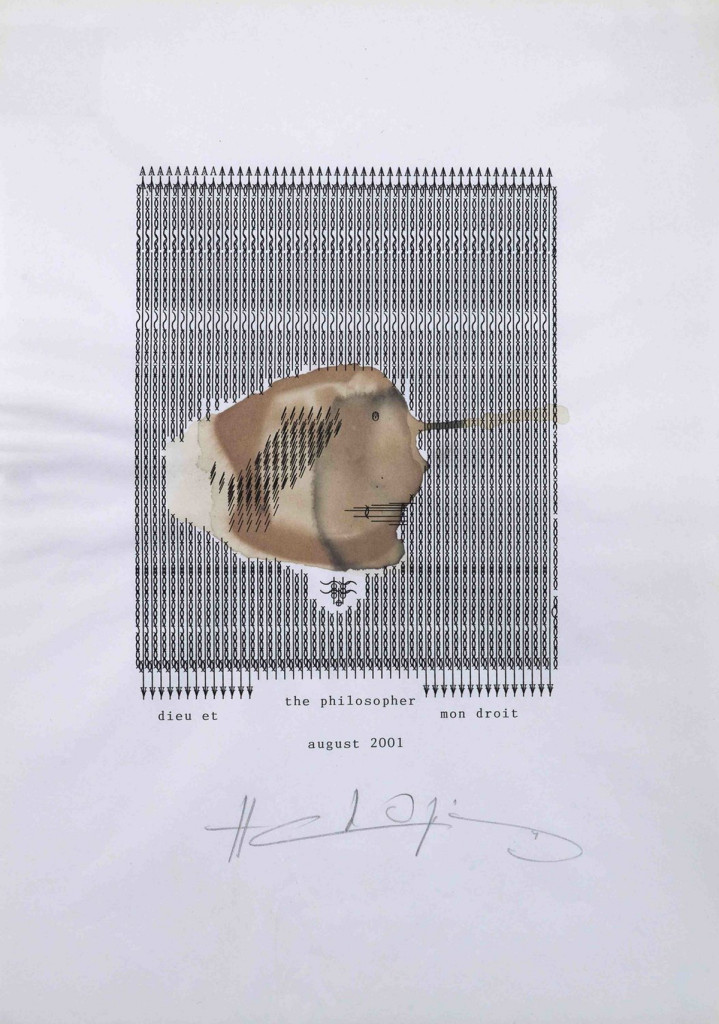

4. Henri Chopin, Bush, 2001. © the Estate of Henri Chopin. Courtesy Richard Saltoun, London

5. Sam Winston, Backwords (plate), 2013. © Sam Winston, Back Words, 2013

6. Sam Winston, Backwords, 2013. © Sam Winston, Back Words, 2013