The top floor of a modernist apartment block seems an unlikely location for the studio of an artist best-known for his engagement with botany. Nonetheless this is where we find Alberto Baraya, one of Colombia’s most prominent contemporary artists: his working environment not the cavernous white-walled spaces favoured by Bogotá’s other leading practitioners, but a small carpeted flat piled high with paraphernalia.

I’m here thanks to Dr Crystal Bennes, my wife, who is curating 4.59,74.0, an audio map of Bogotá featuring Baraya and a number of other Colombian artists. While they’re discussing ideas, I have a snoop: dozens of fake plastic flowers lie under a table; small, stuffed, brightly-coloured birds perch atop shelves of dark wood. Outside, the bright-lit sprawl of Bogotá extends endlessly into the night.

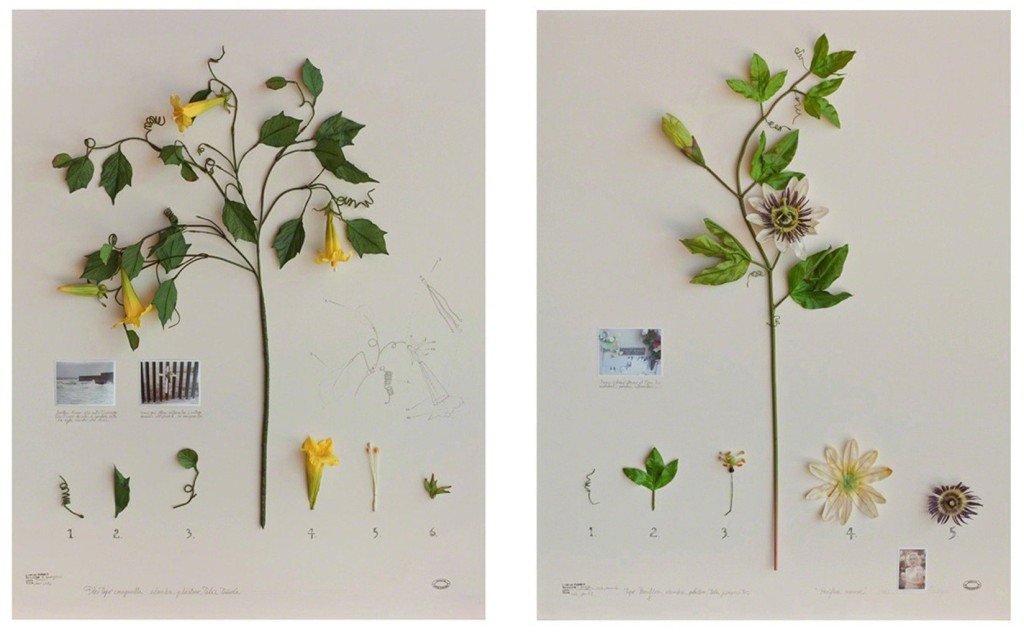

Baraya’s most widely acclaimed work is the Herbarium of Artificial Plants, a project commenced in 2002 and continuing (on and off) even to this day. Over the years, Baraya has collected a vast array of artificial plants – in fabric, glass and plastic – from Colombia and across the world. Each specimen is attached to a mount and surrounded by notes and diagrams that serve to pin the plant in place. The resulting works exemplify Baraya’s interests in the histories of art and science, the inextricable links between botany and colonialism, and the oft-troubled relationship between humans and the environment.

Baraya, who represented Latin America at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009, is not the only artist in Bogotá interested in such issues. A whole host of contemporary artists have emerged for whom nature is a long-running area of fascination. Several are exploring issues that are urgent the world over: our increasingly distant relationship with the natural world, issues of global warming, technological mediation, and the legacy of the sublime. Others are exploring specifically Colombian issues.

Such work is a product of colonialism’s inextricable relationship with the science of botany.

The most interesting are doing both: the likes of María Fernanda Cardoso, currently fascinated by flea circuses; José Alejandro Restrepo, best-known for an installation of bananas and news footage; Miguel Angel Rojas, for whom coca leaves have been a key material; and Miler Lagos, who is currently classifying candies as if they were gemstones. Rosario Lopez, another artist involved in 4.59,74.0, employs photography and installation to engender bodily interactions with vast South American landscapes – empty, but full of lives and hidden histories.

In the last year, this kind of work has gained a focal point through the opening, in August 2013, of FLORA. With the tagline “Ars + Natura”, FLORA is a multi-purpose space (with studios and galleries, screening room and shop) set up by Jose Roca, a curator with a long-running and well-defined interest in art that intersects with environmental issues. He is also one of the most prominent figures in the Bogotá art scene: in addition to FLORA, he is currently Adjunct Curator of Latin American Art at Tate where he advises on the institution’s acquisition’s policy in the region. Previously, he curated the São Paulo biennial in 2006, and for ten years managed the arts programme for the Banco de la República in Bogotá.

The bank’s collection is rich in art that engages with nature. Highlights from its museum in Bogotá include three photographs from Juan Fernando Herran’s 2006 Campo Santo series, depicting makeshift crosses half-hidden in tangled woodland undergrowth; Maria Elvira Escallon’s photographic series, Nuevas Floras (2003) of trees morphing into decoratively carved sculpture; Baraya’s Herbarium of Artificial Plants; and Mario Opazo’s 2010 video Solo de Violin, which sees the instrument played, Eolian Harp-like, by the wind itself.

So what lies behind this ongoing artistic engagement with the environment? Roca sees such works as a product of Colombia’s colonial history, and, more specifically, colonialism’s inextricable relationship with the science of botany. “More than environmentally-concerned,” Roca told me, “art in Colombia is interested in the political implications of the scientific discourses.” This viewpoint is expounded in more detail in his 2003 essay, Necrological Flora: “The interest in botany, a science identified in the imaginary collective with the classificatory craze of the 19th century, has sprung up again as a theme and as an artistic strategy in Colombia,” he writes. “But in the same place where the voyagers saw the symbol of pre-cultural, savage nature, contemporary artists identify the long-term effects of a transplanted economic model and of the resulting asymmetries in the distribution of wealth.”

The continuing influence of colonial figures on contemporary scientific understanding is unavoidable. Bogotá’s leading biodiversity research centre, the Instituto Humboldt, was founded in 1993 and named after nineteenth century Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who travelled throughout South America between 1799 and 1804. The city’s botanical garden, meanwhile, was founded in 1955 and takes its name from Spanish priest and botanist José Celestino Mutis.

It was arguably Christianity that first institutionalised mankind’s perceived superiority over the natural world.

As both priest and botanist, Mutis is a key figure. It was arguably Christianity that first institutionalised mankind’s perceived superiority over the natural world. As we read in Genesis 1:26, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky…” It was this divine justification that underpinned the colonialists’ sense of superiority over the so-called New World. In Short Walks from Bogotá, Tom Feiling cites Jesuit naturalist, Jose de Acosta, who went so far as to claim that God placed precious minerals in South America so that Christian Europeans would come, conquer, and “communicate their religion of the true God to those who did not know it.”

At the same time, it was through botany that such hierarchies (with white Europeans at the top) were transferred from religion to science. As Roca’s essay continues: “Part of the tragedy that derived from this ‘new conquest’ arose from the fact that the scientific viewpoint supported a social order that was based on the idea of exclusion. This social hegemony, blatantly unequal and unjust when viewed from a modern perspective, was made to look as the natural order of things, an order which was by nature unquestionable.”

The lasting influence of Mutis feels therefore appropriate. He is best known for heading the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada between 1783 and 1816 during which some 6,000 new species were described. A staggering 6,717 drawings were produced, but it was not until 1952 that the governments of Spain and Colombia commenced the publication in full of Mutis’ Flora de la Real Expedición Botánica del Nuevo Reino de Granada. Since then, one volume was published on average per year up until 2002, making for a total of no less than 51 volumes.

Botanical drawing was one of the first independent threads in Colombian art. It marked a point of departure from the art that had come before.

This work (a full set of which is in the library at FLORA) is a clear influence on Baraya’s never-ending Herbarium of Artificial Plants. Indeed, the artist credits its publication with spurring a new wave of artists to look at Colombia’s colonial legacy of botanical drawing. He sees such work as significant in the construction of the country’s identity post-independence (which came while Mutis was still on the continent). “Botanical drawing was one of the first independent threads in Colombian art,” he says. It marked a point of departure from the art that had come before, be that indigenous or religious.

In addition to Colombia’s colonial history, Karen Abreu, Co-director of Bogotá gallery Instituto de Vision (producers of 4.59,74.0) attributes the current interest in nature to the ever-presence of the natural environment around and even within the city itself. Many residents make regular retreats to their fincas in the lushness of the countryside, while the unique cloud forest of Chicaque is just half an hour away. All the while, the misty pine-clad mass of Monserrate mountain is a constant, soaring presence within the city – providing an unfailing landmark and blocking development to the east. As artist Rosario Lopez comments in Un Atlas: la obra de Rosario Lopez: “here – simply by being in Bogotá – anyone has the opportunity to look spontaneously at the hills and mountains.” She compares this to the complete lack of tangible geographic features in cities such as London, where she was a student at Chelsea in the 1990s. “I utterly missed the landscape,” she said of her time there.

This is perhaps fitting given Colombia’s extraordinary diverse landscape: from tropical rainforests to Andean peaks, plains, glaciers, coasts and deserts. Thanks to such geographical range, Colombia is said to be one of the four richest countries in the world in terms of biological diversity, with over 1,800 species of birds alone. It is impossible, however, in a country such as this, to separate landscape from history and politics. Asked to explain Colombia’s extraordinary stretches of untouched wilderness, Baraya touches upon an unlikely source: civil war.

Colombia has been at war with itself pretty much continuously since 1948. First came the ten-year countryside war between the Conservatives and the Liberals, known as La Violencia, in which some 200,000 people died. In 1957 a bipartisan coalition known as the National Front was formed between the two, which may have ended one war, but it paved the way for another. The exclusion of other political voices from mainstream debate, and the US-backed repression of Colombian communism, led to the rise in the mid-1960s of various left-wing groups such as the FARC and ELN. The ongoing war between government forces and these guerrillas has been exacerbated by the rise of right-wing paramilitary groups. It has also seen the rise of narcotrafficking despite prolonged American military intervention as part of successive presidents’ War on Drugs and the controversial Plan Colombia. A further 220,000 people have died.

It is through fear that the urban has become a place of refuge, however precarious.

During this time, Colombia’s urban population has swelled exponentially with those retreating from the violence of the countryside. Between 1985 and 2012 alone, some five million civilians were displaced. In that time, the country’s urban population rose from just under 20 million to just under 32 million, while the rural population actually fell from 10.5 million to 9.5 million. It is through fear that the urban has become a place of refuge, however precarious, and the countryside has consequently remained largely untouched. There remains, out there, a kind of wildness.

Alberto Baraya explored precisely this relationship between landscape and violence in a short 2005 video piece entitled El Rio. In it, the tranquil idyll of a classically composed river view is violently disturbed by gunfire directed at the water. Baraya had been filming from a military vessel; the gunfire, he says, “a projection of the soldier’s own fears”. After watching the short film in his studio, Baraya turns to me: “In Colombia, the beast is not only the tiger,” he says, “but also the guerilla.”

But this might be about to change. The recent re-election of neoliberal president Juan Manuel Santos means that peace talks are continuing with the two main guerrilla organisations: ELN and the FARC. If the talks progress, as is hoped, then the countryside will be safe once more – safe, that is, for development.

I spoke to an official in The Ministry of Environment and the Department of National Planning (housing and conservation were merged under Alvaro Uribe, Santos’ predecessor as president). She told me that they are already planning ahead for a Colombia free from war. The issues, she said, are twofold: how to maintain conservation when areas start opening up for development, and how to ensure the profits generated remain within the country.

School taught us that stones are a world devoid of life. Art has taught me how wrong school was.

A nearby example comes in the form of Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, who has consistently refused foreign companies access to his country’s vast supplies of lithium. Colombia’s conservation officials are watching him with interest. But it won’t be easy: mining and oil drilling permits are already being issued in conservation areas, especially near the border with Venezuela. As much as peace is to be welcomed here, it is hard not to fear for the future.

What is the role of the artist now? One possible pathway: to subject to sustained and thoughtful critique the assumptions that underpin our actions and our (mis)understandings – especially with regards to the environment and our relationship to it. Colonialism has shown what terrible damage can be inflicted through the violent imposition of a skewed worldview. As Rosario Lopez has so eloquently put it: “School taught us that stones are a world devoid of life. Art has taught me how wrong school was.”

Dr Crystal Bennes is Poetry Editor of The Learned Pig. You can find out more about 4.59,74.0 audio map of Bogotá at 459-740.tumblr.com/

Image credits (top to bottom):

Juan Fernando Herrán, Campo Santo, 2006

Alberto Baraya, Expedición Califórnia: Campanilla Tijuana, 2012

Alberto Baraya, Expedición Califórnia: Passiflora Monroe, 2012

Miler Lagos, Archaeology of Desire, 2012 (installation view)

José Alejandro Restrepo, Musa Paradisiaca, 1993-1996

Real Expedición Botánica del Nuevo Reino de Granada, 1783-1816

Rosario Lopez, Insufflare, Romilli 01, 2007

Alberto Baraya, El Rio, 2005