There’s something intrinsically interesting about symbiosis – not only in and of itself, but also as a model for new ways of thinking about relationships between, for example, art and science, or humans and the environment. California-based artist Amber Stucke has been exploring symbiosis, as well as ideas around consciousness and embodiment, for the past few years. Her thesis was entitled Embodying Symbiosis: A Philosophy of Mind in Drawing, and her work spans writing, painting, interactive installation, and drawings of eviscerating precision.

We emailed Amber some questions about her work. Here is what she said (US spelling retained).

What is it that interests you about the idea of symbiosis?

The first time I ever saw the word symbiosis was when I was doing research for an earlier project called Twinship: Unity in Difference. I was reading non-fiction material on behavioral traits related to both fraternal and identical twin relationships. This project stemmed from my own curiosity of being a fraternal twin myself. The word symbiosis is used to describe the strongest bond between two human beings: that of an identical twin relationship.

The word came up again but in a more indirect way through personal experiences and encounters with Lakota Sioux and Ojibwa people in the Midwest. In biology, symbiosis is understood as the interactions between two organisms and their long-term interrelationship. The Lakota Sioux have a phrase in their language called mitakuye oyasin, which translates as “all my relatives”. This phrase encapsulates the worldview of interconnectedness held by the Lakota people. It is this interconnectedness between nature and culture where the word symbiosis falls into place.

Consciousness is often understood as a point of division between the human and the animal (something you touch on in your thesis). Could you describe the role of consciousness in your work?

The role of consciousness in my work is complex. It starts with my personal beliefs about consciousness. I see the mind and body as one, and not separate entities. I not only believe that consciousness is biologically connected to my entire body, but I also believe in other consciousness all around me – plants, animals, insects, fungus, etc. Without having a division of consciousness between the human and the animal, it opens up more unknowns and possibilities in research and exploration of consciousness. I am not the only one who has unearthed this area of inquiry. People such as Michael Pollan, Terence McKenna, Jeremy Narby, or Donna J. Haraway also continue a dialogue and research on awareness of other intelligence and consciousness beyond human beings.

The act of drawing becomes a form of

artistic research documenting consciousness.

In your thesis you write: “I am drawn to investigate how my body experiences and learns from the world around me through drawing.” Could you elaborate on the way that drawing functions as a kind of intermediary here, and also how it does so differently from, say, writing or ‘merely’ touching?

The act of drawing becomes a form of artistic research documenting consciousness. By understanding that consciousness is a vessel for sensation and perception to experience the environment and to gain knowledge, it can be recognized as this intermediary. Embodiment, or consciousness embedded in the body, describes how I view my body connected to my drawings. It is through my embodiment of symbiosis that defines my physical body as a device to gain knowledge from my lived experiences.

The act of writing does not require the body to stand for hours to process and create forms, nor does the act of “merely” touching require the body to engage with a material, such as graphite, that translates consciousness into a visual format. Drawing as an act of embodiment becomes an intermediary between the drawing and the artist and also between the drawing and the viewer. The completed drawing or document should provoke more questions than answers and should also engage the viewer’s visual sensory to provoke a phenomenological experience.

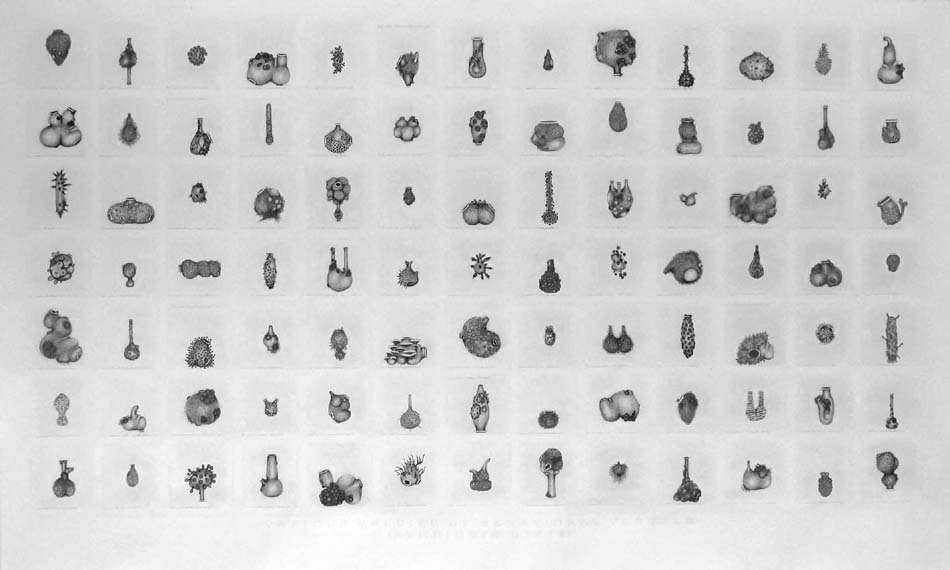

Your drawings have an almost scientific or diagramatic realism. How important is that element of your work?

It is very important. The appropriations from visual scientific illustrations allows for my work to sustain a constant dialogue between art and science, and between systems of knowledge and belief. I appropriate from these visual taxonomies to create conversations between local knowledge systems of the human body and scientific classification structures. Both the rational and experiential come together within the “diagramatic realism” to further an open-ended critique of what a knowledge structure is and what it can become. I also utilize imagination within this format as an agency, which challenges the scientific framework.

Both the rational and experiential come

together to further an open-ended critique

of what a knowledge structure is.

What were visitors expected to do with the spore-dusted papers in your participatory sculpture? Do you know what any of them did do? Does it matter?

The visitor is asked to take one sheet of paper from the stack with knowledge that the paper is dusted with wild mushroom spores. I do not expect anything from the visitors or audience. No matter what, once he or she takes a sheet, they are spreading the spores into the environment – giving more opportunity for the spores to find ground to make more of themselves; in a sense evolving the species of mushrooms. It is also up to the imagination of the visitor to do whatever they want with the piece of paper. This piece allows for the participant to become the intermediary between nature and culture.

What are you working on at the moment?

Currently, I am working on more studies connected to sexual relationships within Symbiosis State. These specific drawings look at how color is related to attraction connections under symbiosis. It asks the question: how can colors attract and create symbiotic relationships?

I am also trying to expand my participatory sculpture with mushroom spores to more communities outside California. This piece involves locally foraged, wild mushrooms to be collected within the surrounding area of where the sculpture will be interacted with. If I place this sculpture somewhere in London, Berlin, New York, or Chicago, I would ask a community of volunteers to collect the mushrooms in the nearby forests with me. The location would determine when I could actually collect the mushrooms – a certain time of year when there is rain present. This would give the opportunity for the community to look more closely at and to have knowledge of fungus in the surrounding area, and it would also expand upon my ideas of interactions between nature and culture under symbiosis.