Nikolai Vavilov (1887 – 1943) was a Russian agronomist, botanist and geneticist, and also the main character of the newly launched podcast Seeds. Driven to end world hunger, Vavilov collected a huge amount of seeds from agricultural crops all over the world, forming the world first seed bank. His vision was however in contradiction to the one of Stalin, leading to his imprisonment in 1940 and death only three years later. When No Stone Theatre director Nicolas Pitt heard about this story, he knew it had to be brought to the public.

Originally created as a theatre play, it became impossible to tell Vavilov’s in the theatre halls story due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Instead of a live performance, the play was turned into a podcast. Each episode has been released in association with different institute throughout the UK.

Let’s start at the beginning. How did you hear about Nikolai Vavilov and his team, and what inspired you to bring this story to stage?

A friend who had seen some of my previous work asked if I had heard of this incredible tale of the world’s first seed bank, and what happened to it during the siege of Leningrad. I had not, and as soon as I started looking into it, I knew it was something that would be incredibly rich and vital to explore for today’s world. When my co-founder Johanna Taylor and I started No Stone, we wanted this to be our first major project together.

The story of the siege in Leningrad and its wider resonances lend itself fantastically to a piece of live performance. You can both explore the intense crucible like situation of hunkering down in a room during a siege, while also having the possibility of exploding out from that setting to investigate the wider environmental and social themes and other timelines. For example, we wanted to examine the detail of how complex and interconnected our food system is, and how that intersects with the way we see and experience the natural world. Where for example all the ingredients in your shop bought smoothie come from, and the impact of those being so available to us.

We wanted to examine the detail of how complex and interconnected our food system is.

From very early on the creative team knew that the core of the story had to be inspired by the workers during the siege, but we wanted to find modern lenses and perspectives to elevate it from a simple period piece. This led us to explore formal devices and ideas around how we remember our histories, our relation to these real and imagined spaces and how we could translate the real story in a way that maintained its integrity. I think that the transition into a piece of audio drama has both followed that through and hopefully, with the character of the patient, further enhanced it.

It must have been very interesting to translate the play into a podcast. Could you tell us more about how you experienced this process?

Interesting is the word! Like everyone knows, being thrown into lockdown was a whirlwind experience while also being incredibly still at the same time. We were really grateful that the Arts Council awarded us funding so we could finish the piece’s development and get it to audiences during this difficult time. I had not made anything episodic before and that stage we had about 1 hour of stage material, which included a lot of highly visual work using movement and projection, which needed a new form for it to work as just audio. However, once we started to interrogate the material from this perspective, and the fine work of Nick Walker and Jon Ouin (text and sound) started to take shape, it naturally expanded into the 8 episodes we have now. The work we had already done paid off in how we knew we could tell the story and create the worlds we wanted it to live in. In many ways the rhythms of lockdown were great for this collaborative process as we had more time to work on bits between the sessions where we could come back together.

The real challenge came with the recording of our wonderful cast. Still under lockdown we recorded all the dialogue remotely, with each actor dialing in from their house. We worked with a sound engineer who talked them all through turning their rooms/cupboards/attics into ad hoc recording booths and – despite some wifi challenges – were able to recreate a virtual studio environment and work in many ways like we would if we were together in the rehearsal room. While we all missed the fun of being together and comparing lunches etc. it was a privilege to be creative with other people during such a weird time. The last bit of the process was Jon and I working on the final compositions of the episodes. It is here where his talent really shines through, and it has been a pleasure to facilitate it.

Even though the story of Vavilov took place in the beginning of the modern century, it resonates with issues of our current times, such as starvation, pseudoscience and loss of biodiversity. Could you reflect upon this? And did you take those current issues into account while working on the script of the play?

The parallels are stark and incredible, and more amazingly the pandemic and lockdown only seemed to make them more pressing and relatable for today’s audiences. So yes, we absolutely took them into account by turning up some of the volume around the pseudoscience of Vavilov’s time and the food security/scarcity issues we are facing now. When I first started working on the story, “biodiversity” still felt like a niche subject and it is heartening to see that over the last few years it become increasingly part of our lexicon, so I knew that people would connect with Vavilov’s story and institute as it so beautifully encaptures it in the form of something so small, simple and beautiful as wheat seeds. Also, our connection to food is unavoidably cultural, sometimes sentimental and in many ways spiritual. The act, for example, of eating bread that is the same as our forefathers, connects us to a lineage of human experience that I think everyone can understand and connect with.

Also, our connection to food is unavoidably cultural, sometimes sentimental and in many ways spiritual.

I am very curious about your own understanding of current issues regarding seeds, food sovereignty and agricultural policy. Has working with the story of Vavilov changed this somehow?

Yes it has, by making me more aware of the issues you mentioned. Before working on the piece, I had a fascination and love of food and food culture, and an interest in environmental conservation. But learning more through the lens of this story really expanded my horizons, and the drive, ambition and scale of Vavilov’s work unlocked an appreciation for how we as individuals and collectively can change things for the better. Vavilov’s mission was to end world hunger, but still today despite billions of obese people hundreds of millions still do not have enough food to survive. The agricultural policies that have given us higher and higher yields are huge drivers of climate change and have badly affected soils, ecosystems and vital biodiversity that we often lose before we know it’s true impact on our future.

When you also realise that corporate interests not only drives this process but also erodes traditional farming methods and produce – favouring instead homogeneous crops that often damage the grower’s land, rob them of their culture, do not give them the return they need and entrap them in debt to the company – it is hard not to see the need for urgent systemic change to redress these balances. At the same time the scale of say “eating an apple a day” for a country like the UK (that would be hundreds of billions of apples a year) you appreciate how great and complex these issues are for all of us.

The play originally titled Seeds of Hope. Could you explain your choice for this title, and how it relates to both Vavilov, as maybe your work as a theatre director?

At the core of this story is one of hope. The sacrifice of those brave and principled scientists and workers at his institute – and of Vavilov himself in trying to stand up against damaging pseudoscience that would lead to mass famine and so dooming himself to being “removed” by Stalin – is vindicated in that their vital work and ideas are carried on today. That by thinking of our future, and taking difficult but heroic action now, we can overcome the seemingly impossible challenges we face. But to do so we must listen and value Science and process and understand our past. My work as a theatre director and artist is focused on being a part of that process, and aiming to give a type of humanity to these stories and challenges.

We actually changed the title just to “Seeds” as we didn’t want to give away too much of the ending, or pass too much judgment on what the story “means”. I think it stands for itself and audiences can make up their own minds in that regard. What happened in Leningrad, what has happened to the natural world and what is happening during the pandemic is frightening and messy. It is what we chose to do form here that will be the hope that we all need.

Seeds is directed by Nicolas Pitt, produced by Johanna Taylor, text by Nick Walker and Music & Sound design by Jon Ouin.

Starring: Nina Sosanya, Katy Stephens, Graeme Rose, Kirsty Rider and Jordon Kemp.

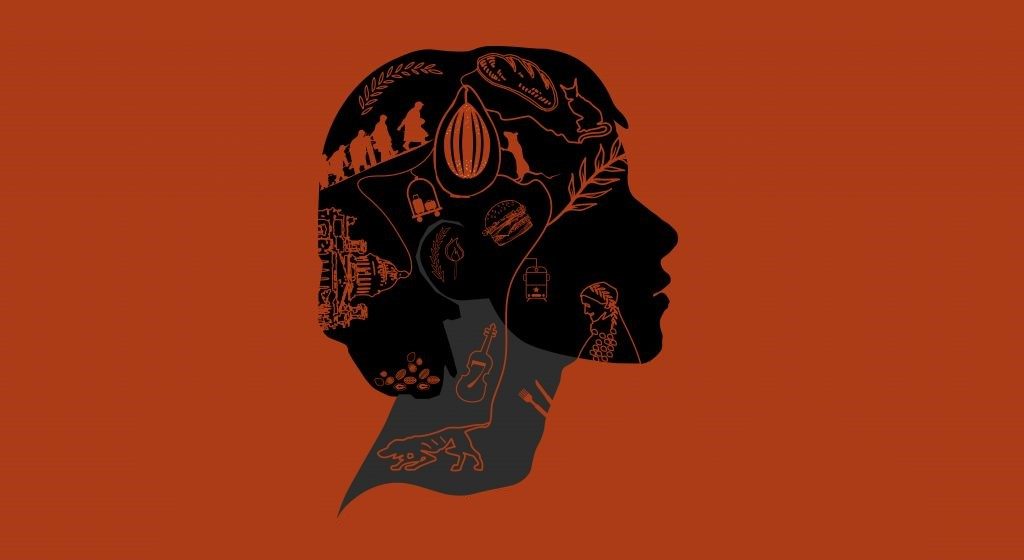

Artwork is illustrated by Gemma Hattersley.

Listen to the episodes on the website

And if you’re interested in Nikolai Vavilov, take a look at Sergey Kishchenko’s Observation Journal, an extraordinarily detailed and wide-ranging project which began in 2014 and continues to this day.

This is part of FIELDS, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring fields as natural and (agri)cultural, invisible and visible, poor and productive, created and creators. FIELDS is conceived and edited by Marloe Mens.