How can we make visible something that has been invisible for so long? + Other Cartographies makes visible the invisible. The recompilation of histories of female cartographers is a challenge since most of them have been erased from History.

As a graduate in architecture, my fascination with cartography started when I was in my second year of university. A professor introduced me to the term, ‘psychogeography’. In Guy Debord’s words, it means the study of the precise laws and specific effects on the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviours of individuals. I started to implement the concept from a feminist perspective in the analysis of design. I used my body in the site analysis and worked on the design based on my sensations, perceptions, and intuitions. It wasn’t until I found out about a book called Maps World: A History of Women in Cartography when I realize that women have been map-making for a very long time and acknowledging their bodies through cartography.

The first map that I found was by the indigenous Shanawdithit (Canada, 1801). In her cartography, she takes into account two different contexts. One of them is about her aunt Mary March’s taking on the north side of a lake and the other being a representation of a European captain visiting the Beothuk tribe at the south side of the lake. All of these events are focused on the lake. The lake, the territory that has seen her grow, became a dichotomy between the fear of being killed and being able to call the lake ‘home sweet home’.

The first map that I found was by the indigenous Shanawdithit (Canada, 1801). In her cartography, she takes into account two different contexts. One of them is about her aunt Mary March’s taking on the north side of a lake and the other being a representation of a European captain visiting the Beothuk tribe at the south side of the lake. All of these events are focused on the lake. The lake, the territory that has seen her grow, became a dichotomy between the fear of being killed and being able to call the lake ‘home sweet home’.

This alternative approach, which takes into account the female’s body, cares, affections, emotions, and other elements on a map traditionally not taken into account, is what persuades me to keep researching about the deconstruction of maps. One of the pioneers in this approach of map-making and map reading is John Brian Harley. In his article, Deconstructing the Map (1989), Harley explains how deconstruction urges to read between the lines of cartographies. To discover the silences and contradictions that challenges the apparent honesty of the image. I decided, from a feminist perspective, to research maps made by women, and to understand their cartographic silences to gain a better understanding of their quotidian life.

I had more than fifty female cartographers, and cartographies archived on my computer’s desktop, and I wanted to make their contribution and work visible inside the field. I decided to create an online digital archive where anyone can see and appreciate the contributions of these women. That’s when www.othercartographies.com was born as part of my final Master’s project. The purpose of this archive is to understand power and resistance through spatial and cartographic knowledge through these women’s work. We can establish new practices in feminist geographies as these cartographies enable us to create new methodological alternatives in public/private spaces and territories.

Three female cartographers work on these alternatives are Emma Bourne, Myra Zimmerman, and Mary Sherwood Wright. Their cartographies represent how women combine wage-earning and domestic responsibilities. On Bourne’s “America – A Nation of One People from Many Countries” (1940) map, what stands out is the picking of oranges. By that time, the military looked for ways to get Vitamin C to overseas troops in WWII. The labour of immigrant women and men for the collection and production of orange juice was fundamental to prevent scurvy.

Three female cartographers work on these alternatives are Emma Bourne, Myra Zimmerman, and Mary Sherwood Wright. Their cartographies represent how women combine wage-earning and domestic responsibilities. On Bourne’s “America – A Nation of One People from Many Countries” (1940) map, what stands out is the picking of oranges. By that time, the military looked for ways to get Vitamin C to overseas troops in WWII. The labour of immigrant women and men for the collection and production of orange juice was fundamental to prevent scurvy.

Zimmerman’s “Le Vieux Carre de la Nouvelle Orleans” (1942) map references a timeline from when the French claimed the territory in the late 17th century until it became a US territory. The women represented on this map are African-American women called ‘praline mammy’ and casket girls. The praline women became some of the most popular of New Orleans’ street vendors. They became the face of the candy in the city. They would cook, clean, and sell this candy. It was their source of income. The casket girls lived with the Ursuline nuns. They were educated and stayed with them until they were married off to men of the colony.

Sherwood’s “Home Arts” map (1938), consists of various regional needlework, crafts, and cooking throughout the USA till the 1930s. She focuses on women working in a domestic environment, the ones holding an object and going somewhere, working in their house, always for the use and pleasure of others.

It’s important to highlight this project’s manifesto:

Throughout history, women have been recognized for their achievements at a precise moment, but written off in the historical context. Although equal rights movements have prospered since the 20th century in the interdisciplinary division, female cartographers fall into this kind of invisibility. Many have written about the oblivion of women in different disciplines but this digital archive highlights the contributions of women in the cartography world.

Cartography has been fundamental to understand the territory and the spaces within it. The fact that female cartographers’ work has been overshadowed by the Patriarchy has helped them formalize a new approach where subaltern groups are noticed and represented in the maps. This powerlessness gave women the courage to express geography in a different perspective; theirs.

My intention with this project is to make visible these women and demonstrate that women know how to map, although most of them have been erased from history. The intertextuality on these cartographies is highlighted in cares, time, bodies, affections, solitudes, and intimacies in different contexts. Women often map differently than men because we have lived different situations, and + Other Cartographies focuses on emphasizing it. Thanks to feminist geography/cartography, we are more aware of the many layers of the territory that are usually hidden with ideologies.

An example of making these inequalities visible is a feminist cartographies series, which I have been working on since last year, called Mujeres en las Calles (“Women on the Streets”). The idea of this series originated while I was reading different articles about the invisibility and the lack of the names of women in public spaces in Madrid. The purpose of these cartographies is to highlight women’s names given to streets, metro lines, zones, roundabouts, and parks. It also includes a brief description of their trajectory and their contributions to the country. It is another way of learning about Madrid’s history from women’s perspectives.

The evolution of cartography has been beneficial, from white settlers using it to conquer native homelands to disrupting the traditions of mapping and reclaiming the power through feminism. The digital archive’s aim is to encourage people to create and use alternative methods when map-making. To think about and add other information regarding marginalized groups and to make visible their contribution in history in order to erase social, political, and cultural hierarchies.

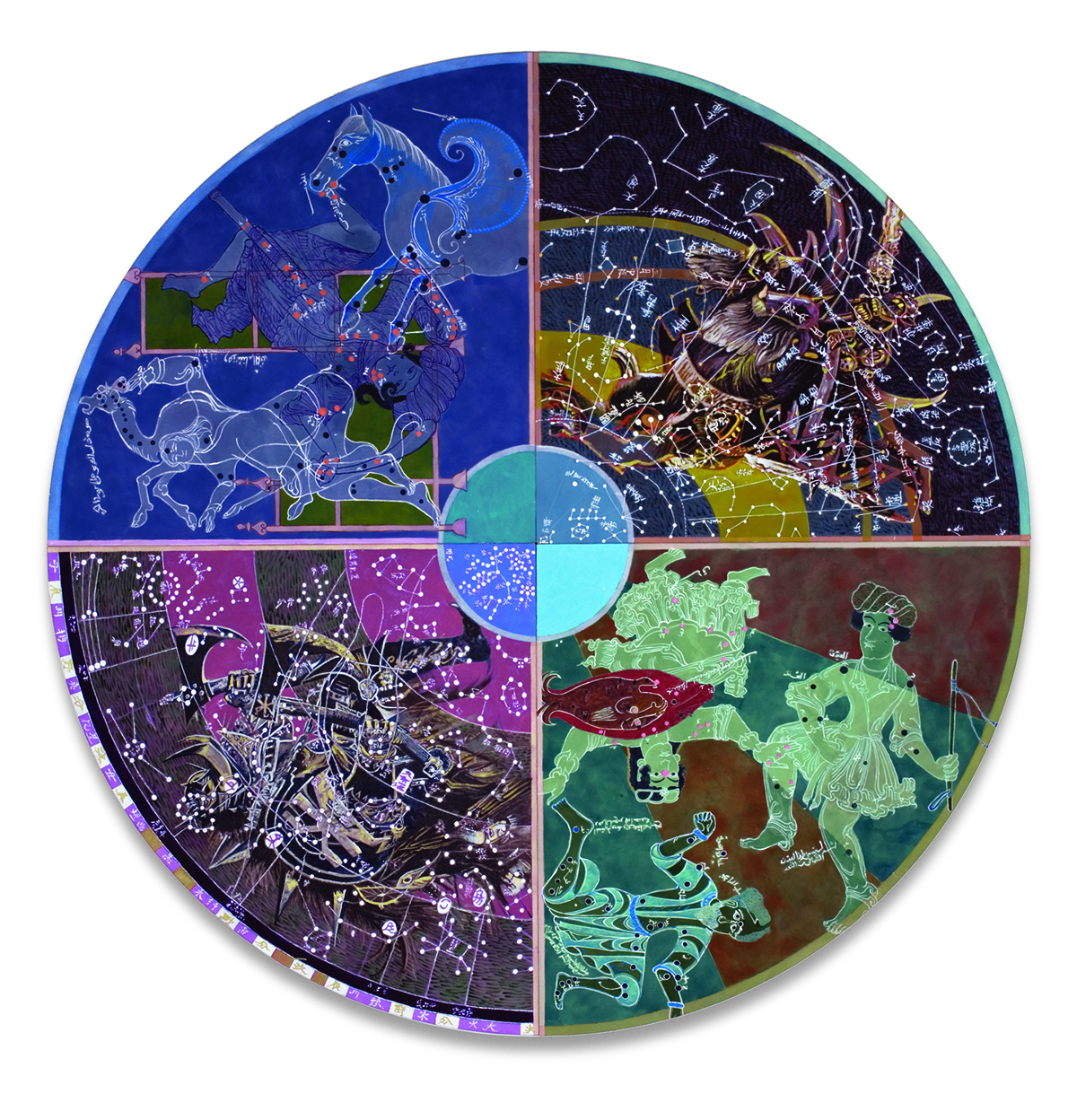

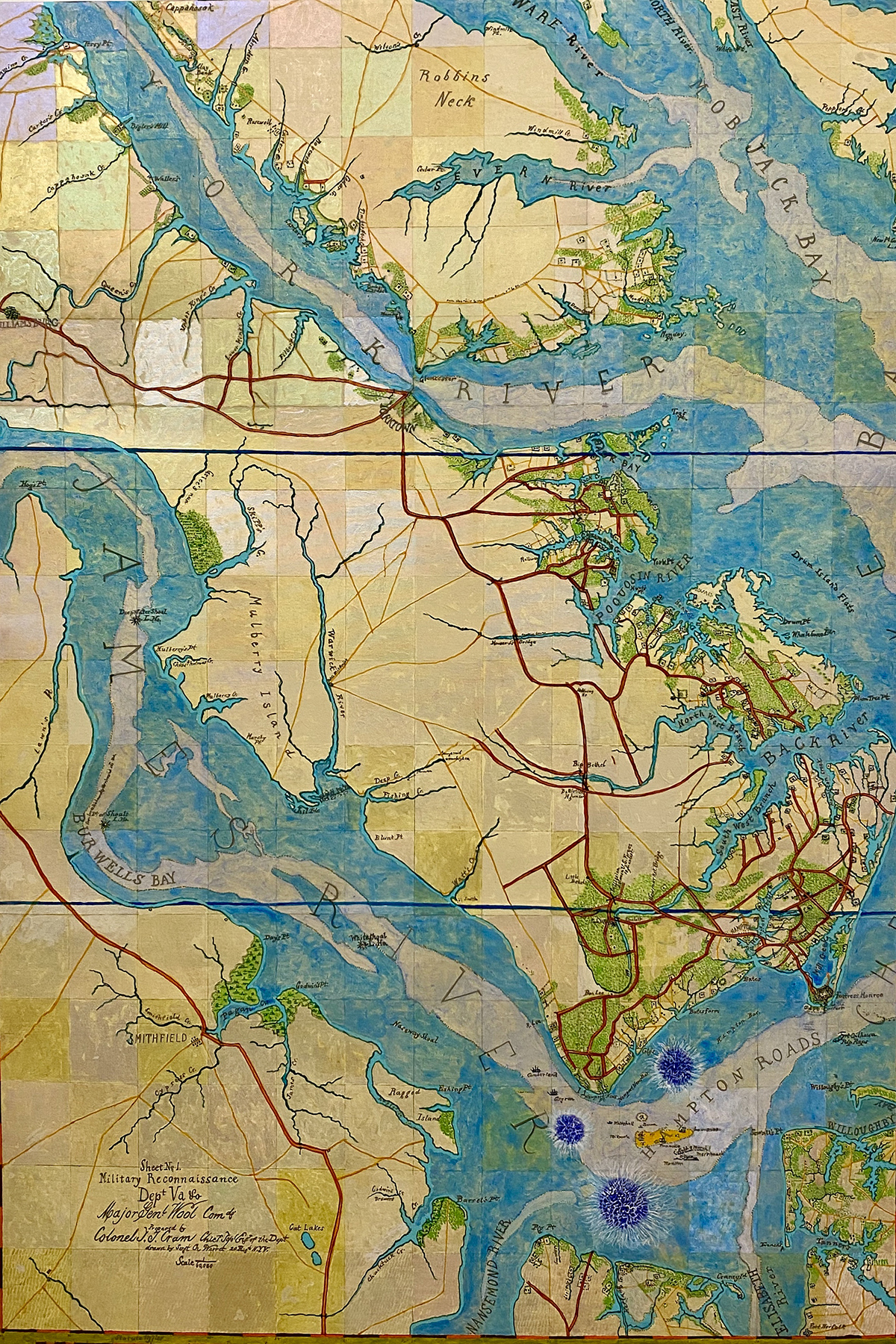

All images are by Joyce Kozloff (born 1942), an American artist whose politically engaged work has been based on cartography since the early 1990s. Kozloff was one of the original members of the Pattern and Decoration movement and was an early artist in the 1970s feminist art movements. She has been active in the women’s and peace movements throughout her life. She was also a founding member of the Heresies collective.

Image credits (from top):

1. Joyce Kozloff, Battle of New Madrid [detail], acrylic on canvas, 2020, 47″ x 40 1/4″

2. Joyce Kozloff, Battle of Fredericksburg, acrylic on canvas, 2020, 56″ x 38″

3. Joyce Kozloff, Battle of Hampton Roads, acrylic on canvas, 2020, 56″ x 38″

4. Joyce Kozloff, Revolver, acrylic on canvas with hardware (rotating mechanism), 2008, 96″ diameter. Photograph by Kevin Noble.

5. Joyce Kozloff, the moments and hours and days of our lives, acrylic, colored pencil and collage on canvas, 2004, 60″ diameter. Photograph by Kevin Noble.

Images 1-3 are based on US Civil War battle maps, created at that time (1860s), and carried by military officers. Kozloff has turned them into paintings, and added viral outbreaks, not to indicate the location of disease, but as a metaphor for the underlying disruptions in our society, which rise up when stirred. As Kozloff puts it: “we are still fighting that war”.

Revolver, which actually turns, juxtaposes two Arabic and two Chinese cosmological charts. Breaking out from behind the opposite Chinese wedges are monsters from the world of Warhammer. The last tondo is based on a cosmological chart of the heavens circa 1660 by the Dutch cartographer Andreas Celarius, overlaid with the tracks of satellites in space, found on the Internet.

This is part of ROOT MAPPING, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring which maps might help us live with a clear sense of where we are. ROOT MAPPING is conceived and edited by Melanie Viets.