Located in Castel Cerreto, a rural area between Milan and Bergamo, lies Tilde: an interdisciplinary space that includes bread making, residencies and exhibitions. Together with husband Simone Conti, Marisol Malatesta runs the bakery, using only natural fermentation and local grains.

Besides baking, Marisol draws, paints and explores the relationship between art and bread making through sculptures. She teaches at the University of Bournemouth, whereby she supports her students to get acquainted with dough, fermentation processes and baking temperatures.

In both your work as an artist, teacher and baker, bread holds a central role. Could you tell us more about this role and how it came into being?

Throughout my career, I always had a strong interest in craftsmanship. Bread making is a practice that includes artistry along with so many other fundamental subjects I consider important in my work as an artist. Bread is a domestic object and a symbol of power: bread connects with our body and memories and at the same time it associates with our relationship to landscape, culture and economy.

I have always been attracted to the processes behind drawing, painting, ceramics and drawing. As an artist, I have spent years gaining these technical abilities. Sometimes, the effort to learn these skills seemed pointless.

However, looking at the increasing predominance of technology today, I think that connecting with materiality is more important than ever. These explorations draw me into bread immediately. In the processes of bread making you must physically connect with the changes of the dough in a rational way (knowledge), but also in an intuitive way (emotional), the same principles that govern painting and drawing. All these psychological connections that are involved in the process of manufacturing is what I’m interested in.

It is like Richard Senett argued: “We are more likely to fail as craftsmen due to our inability to organize obsession than because of our lack of ability.” (Richard Sennett, The Craftsman)

Bread is the oldest food made by men, but is still not simple to make. I am attracted to remarkable dual quality of bread: it is the most essential food item, but at the same time a vehicle for understanding all the incongruences in what we call progress. If we reevaluate bread, we can change our capacity to make, distribute, and consume basic goods outside of a commodity marketplace.

Being an artist as well, do you have the feeling your baking practice differs from bakers that were trained?

Yes, I consider myself an amateur baker.

I have noticed that I have a certain visual way to approach ingredients. I cannot help to think of the dough as a material that has sculptural possibilities: crackers are thin but have strength to create assemblies, biscuits have a density that allows for construction, bread becomes hard like a stone when it dries but is shapeless and adaptable when is hydrated. All these characteristics of food have the potential to make art. This is fun!

All the bakers that inspire me are alternative bakers. Simone, for example, who is my husband and mentor, is a very technical and precise baker but he is also very intuitive when it comes to fermentation. He studied photography, literature and publishing before becoming a baker. Just like him, there are lot of other bakers who had a long career in another discipline. This brings different perspectives to the world of baking. Diversity is making it all more interesting.

I cannot help to think of the dough as a material that has sculptural possibilities.

What I am trying to say, I guess, is that the types of bread we make derive from passion and experimentation, rather then from an orthodox training. The bread we make in the laboratory feels like an extension of the conversations we have with farmers during which we aim to get a deeper understanding of the materials we are working with. Having said this, I also believe that the rules of fermentation are very precise. Timing, temperatures and hydration all depend on the type of flour that is used. So, knowledge and methodology are essential.

Perhaps being an artist gives me the focus on the processes rather then on the final product.

Could you explain a little more about your collaboration with the Art University Bournemouth? How is bread involved in your teachings?

Spazio Tilde, an alternative space adjacent to the bakery, was born from the desire to enhance our bread production on a broader discourse, like health, politics, sustainability, technology, culture, etc. We believe that a diverse range of artistic visions can add an essential critical value to our project. It is a place where ‘bread’ becomes the center of an open discourse.

We welcome different artists to be part of an exhibition each year. We organize an art residency with Vegapunk Studios (Simona Da Pozzo) and Visual Container TV (Alessandra Arnó) in Milan. Simultaneously we work with Arts University Bournemouth. Each year we welcome two fine art students to spend two weeks with us. During this residency, they spend a full day in the bakery with us.

The idea is to create an archive of voices, which can reflect upon the rapid changes within the food industry.

At Tilde, the day is strategically organized around the timetable of fermentation, to make students understand how important time is in the process of bread making. The workshop oscillates between practical activities of mixing, shaping and baking with presentations and discussions about students’ practice, art and bread. At the end of the workshop students get a clear idea, through experience, about the processes of fermentation and the impact it has on our health and on the economic system.

After the students return to the UK, I keep in touch with them doing a one-on-one tutorial to follow up their experience. They are invited to create a proposal inspired by ‘bread’ for an exhibition at Tilde which is part of a broader art festival in Bergamo called ArtDate.

The idea behind Spazio Tilde is to create an archive of voices, which can reflect upon the rapid changes within the food industry.

In our previous conversation, you stated that your bread practice and artistic practice felt like separate fields to you, but that you are starting to notice that they perhaps are not so far apart. Could you reflect upon this?

Instinctively I knew I wanted to learn how to make bread, which was an impulse. Then we decided to open a bakery, and at that point I felt like I was withdrawing from art. It took me a year to learn the basics around bread-making. That was a year in which I did not do any drawing or painting. I realized later that I needed to stop and literally un-learn what came before. Then I slowly started to join the dots and to make connections between things, embracing a more personal and connected way of working.

While distancing from art making, however there was one art piece I made in the past that kept coming back to my mind: Above the Internal System from 2014. A collection of surrealistic recordings of me harvesting, stamping and distilling 300 kg of grapes into Pisco (a traditional spirit from my home town, Ica-Peru). The vines I used, which do not exist anymore, were old varieties that belonged to my grandfather and our Italian ancestors. The urge that moved me to do this work was similar to my interest in bread-making.

In 2019 I made EAT, EAT, EAT, influenced by the dynamics of artisan production and the everyday gestures associated with ancestral rituals. It was my first bread installation. The piece is presented as a pile of mask crackers, fragile elements that form a solid structure – over all a perishable sculpture. This work has connected me back with my practice.

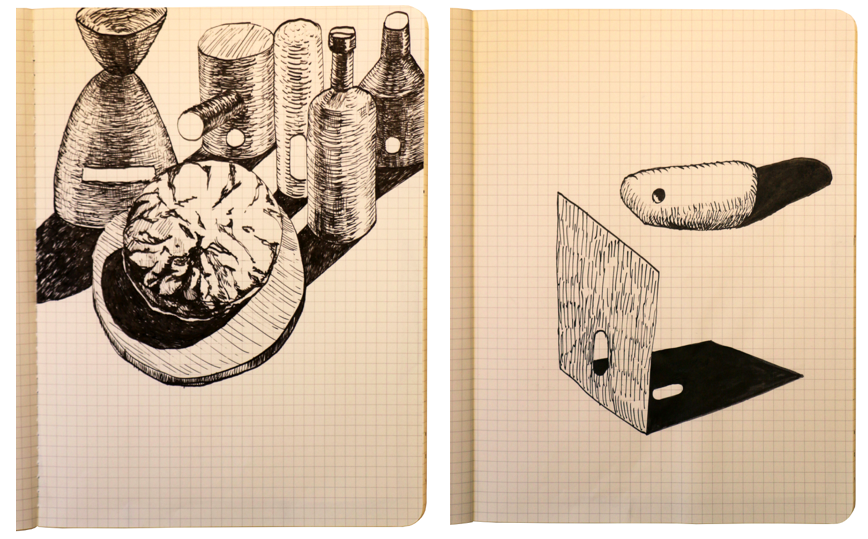

Parallel to this, I am working on a series of ink drawings called Behind the Counter, a record of my everyday thoughts and experiences in the bakery. They feel like a diary. In these drawings, past and present influences and obsessions get mixed up. It helps me to tidy up my thoughts and ideas.

I am still in the process of defining the boundaries between my personal work and the 400 kg of bread we make every week in the bakery. I keep on asking myself the question: what is art and what is not?

This question seems to be mainly about whether something is defined by its process or its final product. Does that resonate with you?

I make paintings and drawings and it is true that they carry this dilemma of the permanent object, paintings more than drawings I think. To balance this heavy weight that painting carries, I try to approach it as process-based, even though there is a permanent reminder as a result.

I come from a very traditional art education in Lima. An education that gives priority to skills and has a strong technical approach. When I say painting, I mean painting: hours and hours and years of training. Sometimes it felt pointless. It was very much an exercise of contemplation during a time when there were very serious and complicated social and political contexts outside the university walls. But we all in some ways learn perseverance and strategies to canalize frustration.

Both painting and bread are the reflection of a process. But both deceive us in their appearances.

With bread the approach is almost the opposite: it’s the final product that matters I believe. Having said that, the process is not removed from its outcome. What I find paradoxical is that even though the outcome of bread is the most important, it is one with an ephemeral existence. Bread has this apparent temporal condition but it carries on living inside people in our cells. It is a fact.

Both painting and bread are the reflection and the result of the process, they go hand-in-hand. But both deceive us in their appearances.

The art system nowadays seems to be built around the idea that it is part of a financial investment structure, something I believe is very problematic. Every artist has been there, either willingly or not. The issue is that in this way, the art market reduces everything to sellable objects. It becomes too predictable, almost the contrary to diversification – which funny enough is recommended by financial experts.

I believe that we can create our own agencies. Artists can structure their own economy by diversifying it and to no only rely on, for example, galleries. I believe there is so much that can be done in terms of how to make a living as artists, without falling into the establish norm.

What I find interesting is that you have moved a lot, from Peru, to London and now Italy. I am curious about your relationship to the landscape and your choice for bread. Do you have the feeling that baking has somehow impacted your relationship to your new surroundings?

The bakeries where Simone used to work in London used wheat from local UK farmers. In a city like London, it’s possible to have access to bread that connects you directly with a different landscape than the chaotic and concrete jungle that surrounds you. It is amazing. When we moved to Italy we knew our project should be build upon two primordial foundations: involving local farmers growing organic and heirloom grains, as well as using natural and spontaneous fermentation.

We are part of an Italian renaissance of the production of traditional grains that had a long history in Italian culture. In Sicily, for example, there are more that 40 varieties of grain being grown like Tumminia, Biancolilla, Saragolla, Bidì, Russello, Maiorca, Perciasacchi. In Piedmont, Marche and Tuscany they grow different varieties too, for instance we use a population that is a mix of Verna, Frassinetto, Solina, Andriolo, Inalettabile, Gentilrosso, Iervicella, Sieve, Abbondanza and Maiorca. A population of grains is when different varieties are grown together, allowing for cross-pollination in the field.

Diversity preserves life and we believe that our small contribution is an act of active resistance.

This experiment is used in the EU to create grains that naturally adapt to a specific territory and have a higher resistance than, let’s say, a monoculture. It is completely opposite to an intensive farming system whereby seeds are mostly controlled by others outside the farm.

The issue with using those grains though is that it becomes very necessary to discuss the costs of their final produce, the bread. Since the grain are mostly grown small scale, the flours cost most then industrial flours and the bread we sell must cost more too. Explaining this to people is the hardest part. It is part of our job to educate and to make people understand that they are not only paying to get a clean, aromatic and nutritious product, but they are sustaining the whole system: farmer-mill-baker.

All of this has a massive impact on the whole food system and with that, the landscape we inhabit. Diversity preserves life and we believe that our small contribution is an act of active resistance, as well as everyone who visits our bakery every day.

Image credits (from top):

1 Breads at Tilde

2 Marisol Malatesta, Eat, Eat, Eat, from the series Primitive Passions, installation view, Spazio Tilde, 2019.

3 Marisol Malatesta, Strange Encounter + Space for Two, from the series Behind the Counter, 19 x 25 cm, 2020.

4 Marisol Malatesta, posters from exhibitions “Prossimo” and “Good Bacteria” at Spazio Tilde, limited edition, 2020.

www.marisolmalatesta.com

www.instagram.com/marisolmalatesta

This is part of FIELDS, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring fields as natural and (agri)cultural, invisible and visible, poor and productive, created and creators. FIELDS is conceived and edited by Marloe Mens.