This is an extract from Listen, we all bleed, a brilliant new collection of essays and other texts by Mandy-Suzanne Wong, published by New Rivers Press, November 2021.

This is an extract from Listen, we all bleed, a brilliant new collection of essays and other texts by Mandy-Suzanne Wong, published by New Rivers Press, November 2021.

You can order your copy direct from the publisher.

Table-Turning

“A table acting in a frantic manner”: making noises “far removed from any approach to common sense” and wiggling unassisted, often with an “agitated . . . rotundary motion.”

~ Anonymous, Table-Turning and Table-Talking Considered in Connection with the Dictates of Reason and Common Sense, 1853

“The futile movements of useless things [in table-turning] are doubly destructive to domestic regulation: their erratic energy prevents persons and things from performing the work expected of them . . . thwart[ing] the rules and logic of domestic spaces . . . [in a] blatant demonstration that consumers had much less authority over things than they liked to imagine.”

~ Aviva Briefel, “Freaks of Furniture,” 2017

Conference Table

Figuring Kathryn Eddy would offer some tasty thesis with a thick sweet glaze of evidence which made even the argument’s bitter sides zestfully necessary, I sat in the audience while she sat on the serving side of a six-foot table; and the rest of us attended, agreeable and relaxed, as to a recitation of the catch of the day. Little did we know Kathryn would transform that university-issue folding table into another table in a windowless room, where instead of rehearsed professorial assurances the cries of the dead came at us from all directions, and papers left to speak in silence for themselves whispered such accusations that made us squirm with deadened stomachs.

She discussed her artwork, The Problematic Nature of Flatness. But this is no flat artwork; this is art with wounding force and incurable affects, art as interrogation and confession, which brooks no doubt as to the identities of the guilty but leaves the vital mysteries unsolved. This is an art of contradiction. With words, pictures, and sounds, Kathryn made painfully present a past and distant installation which was also a twisted performance: nonhumans summoning and playing human beings, turning us into instruments of gut and bone, wresting from us the silences of our complicity in a great conspiracy.

Taxonomy Table

The Problematic Nature of Flatness is an installation in two parts.

Outdoors: a cage, five feet wide. “Human sized,” says Kathryn. Two of her paintings are inmates: a grinning plastic lamb, a beaming toy piglet, cuddly-cute to some, creepy-cutesy to others. The pictures are realistic and meticulously detailed. Some people even worry about them.

Outside, day and night, in the middle of the field, because that, Kathryn says, is “where you would normally find the animals”; the paintings act out a displacement and status interchange. They suffer deportation and deliberate devaluation, stuck outside like trash to endure acidic snow and the excrement of passing birds, to sacrifice their colors to sunshine and smog—and what does that tell you about the conditions of animal life, the counterpart to painting in this trading-places? The gesture implies that the misrepresentations of farm animals by grinning toys and flat, serene imagery were never as valuable as they seemed; but viewers’ concern about the paintings goes to show you the extent to which we humans cherish convenient dissemblings of the origins of meat.

Kathryn throws up a barrier to such convenience, knowing human viewers would just as soon not join the animals in the cage and art connoisseurs would rather not see the fruits of human labor, representatives of beauty and aesthetic practice (which elevated notions are supposed to affirm human sovereignty over other species), given over to the rain and carbon monoxide fumes. “The idea was that this structure would be forgotten and left outside just as the animals that I am referring to are absent from our everyday lives,” she writes. “The inconvenienced viewer walked out into the field and into the crowded confined space to view the paintings… [an] immersive and performative space that mirrored the often forgotten confinement of the animals.” What Became of Your Lamb, Clarice? That’s the title of the plastic lamb’s imprisoned portrait: a quote from Hannibal the Cannibal in Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs. The gourmet maneater refers to a certain lamb who, having been slaughtered for human consumption, haunts the bestseller’s protagonist for life. Hannibal’s question and Harris’ title implicate willful forgetting as a form of smothering; and so does Kathryn’s acrylic-on-canvas captive Plastic Pigs Can’t Scream. The toy may be pig-shaped, its mouth may gape bloodred; but its flat eyes, lacking pupils, belong to nothing that ever lived, meaning the real pigs who inspired the figurine are no longer relevant to it.

The gallery visitor, unsettled and probably freezing (this is Vermont), feeling put out and perhaps a bit affronted, retreats indoors. But before we follow them, note that Kathryn doesn’t exempt herself from the discomfiting exposure to which she subjects her audience. The caged paintings are after all her work, born of physical and mental effort, not to mention time and expense; all of that is in the paintings, and it’s easy to see that Kathryn put as much into them as she would into any piece she put up for sale. Yet she banishes these paintings, abandons them, fully aware of the considerable likelihood that no one will venture out to look at them. With them she banishes part of herself, a foundational aspect of her history and artistic identity. That’s her in the cage. Not just metaphorically but materially. Her vitality caged under the cold sky, foreshadowing with bleak irony what’s to come.

…suddenly all is hush—hush except the songbirds, twitch of a soft muzzle in a bucket lapping, snuffling: ah, a piglet

In the gallery: a table set for an intimate dinner, long-stemmed wine glasses, plates and cutlery, leather-bound menus. At the head of the table, projected on the wall in blue, are numbers, one above the other on a dark background like daily specials on a blackboard in a café. Have a seat. Open your menu. But what menu? It turns out that menu is a disguise for recent annual reports published by leading agribusinesses.

You look at your empty plate, look again at the numbers on the wall. You may not make the connection; there’s no caption. But if the artist is at the table with us (likely), you’ll learn the projection is a “kill counter.” It shows in clean blue figures how many nonhuman animals worldwide have been farmed, slaughtered, and eaten. These numbers increased drastically over time, but Kathryn projects them randomly so you seem to be in the presence of something arcane. They’re no threat as long as you don’t know what they represent, and anyway we’re hearing birds—listen—here come the sounds…

Four loudspeakers, fourteen minutes, enfolding our table in phono: birdsong, a scintillating pool of chirrups spreads out tranquilly before us until chuckling chickens cluck! find us and a sheep brays, off to one side a lamb cries out (the animals are distant or right up in your face depending on where you sit, and they are moving, their voices crawling all over the room) while birds and hens maintain a sort of background texture that is steadily growing bolder, bigger, bulging into the foreground; blaring into your ears, right next to you, close enough to buzz the microphone, is the full-bellied holler of a rooster who is soon joined by his fellows with turkeys adding counterpoint to birds and hens (the overall volume is now considerable) building up to an eruption, a loud deep fearsome moan chased by another and another and a full minute of mooooaanning with clanging and banging and the clatter of chains slashing (it is cows, cows being cows in metal barracks built for cows) in a veritable din, but suddenly all is hush—hush except the songbirds, twitch of a soft muzzle in a bucket lapping, snuffling: ah, a piglet at his dinner, leisurely chewing, smacking his lips with pleasure. The chickens fall silent in the presence of a solemn truth: the coincidence of sustenance and death. And then the piglet, too, is gone. The piece ends softly with oblivious songbirds’ shimmerings.

Kathryn made her recordings at small New England farms and sanctuaries, meaning some of the animals we’ve heard are safe; those in sanctuaries will live out their days with the best care humans can provide. But those in farms are bred for slaughter; by the time their voices reach the gallery, many of them are already dead; nevertheless, says the artist, “voices of the absent animals float, move, hide, and dance around us. We are hearing fleeting memories of them, an embodiment of their being, a melancholy plea… the voices ask something of us.”

Part of what they ask, says Kathryn, is that we stop imposing structures of human meaning onto nonhuman sounds; and that is far from easy, for it seems almost intuitive to make sense of unfamiliar sounds by comparing them to familiar ones: I’ve described the generally unfamiliar cluck! of unmarinated unsandwiched chickens by noting its resemblance to human “chuckling.” But if this kind of mistranslation “seems almost intuitive,” it proves just how deeply we’ve internalized anthropocentrism. Kathryn enjoins us to resist that kind of “ideoagricultural” conditioning by embracing the simple fact (no embrace is simple) that some things just don’t make sense: “When humans start listening to the nonhuman and stop trying to translate everything into our own language, perhaps we will reach a more hospitable understanding. Perhaps listening is the first step towards decentering the human and overturning our anthropocentric perspectives.”

Does Kathryn mean listening like we’d listen to music? For humans, listening to music means making ourselves susceptible to certain sounds, which an artist has chosen and arranged in hope of inspiring us to some emotion. Listening to music means being vulnerable on purpose, to the point sometimes of surrendering to artists’ efforts to make us feel. The urge to dance, the urge to cry, to buy, to write or yell or close my eyes and almost sleep; a sense of the sublime metaphysical or of some movie character’s impending doom; an empathic loneliness or longing; a wish to puzzle out the origins of curious effects; a weird sense of solidarity when music echoing my rage, amplifying my despair, paradoxically makes me feel better . . . Sounds are capable of arousing highly specific, potentially intense emotions; and even when I don’t know what a sound is “of” (sputtering moped, drum machine, hoarse rooster), I am capable of being moved by it. With the ambitious hope of symphonies and songs, Problematic Nature invites me to surrender to that ability, to my own resonant capacity—the possibility that I too may be privy to beauty in a stranger’s voice, in a voice’s living-chicken origins.

You could (almost) say Kathryn’s intention (sort of) resembles that of musique concrète composers like Pierre Schaeffer, who used audio equipment to defamiliarize train sounds by exploring their potential as musical sounds. Kathryn does arrange a nonhuman chorus in a quasi-musical structure to help us hear how strange voices can be; and the contextual shift invites a perspectival one: I hear roosters’ voices differently, no longer just as squawks of the cranky feral varmints who terrorize Bermuda’s parks but as the material potential of artistic beauty. But although the dynamics of Problematic Nature suggest a musical arc, Kathryn is adamant that her work is not music. Music has a terribly anthropocentric history: millions of animals and plants have died for music’s sake; millions of sounds have been silenced or exploited in the interests of illusive musical purity; musical practices are still considered to be primarily (some say exclusively) for humans by humans. Even “heal the world” songs advocate environmentalism not for the sake of the nonhuman hyperentity that is Planet Earth but in order that Homo sapiens may continue to overpopulate it.

What Kathryn wants us to hear in Problematic Nature is how unhuman life can be and still be life. Listen for strangers’ real-life strangeness, listen not for our own sakes but theirs. Many humans are accustomed to silent lambs either cooked or plastic like in Kathryn’s painting; the little terror who screams over the loudspeakers is virtually unthought-of. Nevertheless, a lamb’s life is real life. A lamb’s death is actual death, bloody and unquiet. The voice of a living lamb renders toy lambs and the dead entrée called “lamb” suddenly questionable, outlandish, frightening, and this sound speaks the reality of life: the unwanted reality is that of nonhuman life. The cage and the table in Problematic Nature “play off of each other,” Kathryn says, to the unwanted effects of so much overthrowing: paintings outside, noises inside; humans caged, beasts at the table; around this turning table turn the sounds of eating, but they are the sounds of the eaten! Bringing babbling ghosts of prey into the dining room, Kathryn turns that cozy, familiar place into an estranged site of dissection and consumption: spaces and denizens are problems here, they are questions.

Dining Table

Kathryn has “a problem with flatness,” she says, with pictures’ and sculptures’ “unnerving” tendency to represent nonhuman animals through a “human filter”: not as the animals present themselves but as it is convenient for our species to perceive them. What’s convenient for humans who consume nonhumans is to reduce them to surfaces and silences. This is why The Problematic Nature of Flatness involves so many flat surfaces; there’s the tabletop but also there are walls, projections, reports, paintings, dinner plates, every one of them ethically compromised as their distorted representations of nonhuman animals affirm the ideology that nonhumans are resources. They’re the numbers in the annual reports. They’re the plastic objects in the paintings, created to be stared at, played with, collected. Flatness is the problem out of which Kathryn’s multisensory artwork grows.

The animal is absent from the meat even as it is the meat.

Transforming living beings into quantities requires all kinds of mowing down and ironing out; but to feed the illusion that nonhumans exist for the purpose of being mowed down and ironed out, so that they may be as easily consumed as chicken soup, the flattening processes must be hidden. The flat surfaces in Kathryn’s installation—not only the wall of numbers and leatherette folder, but also the table napkins and even the table—accentuate the invisibility, the clandestine concealment and insidious denial of how exactly living animals become monetary and nutritional values. In the flat and easy simplicity of meat on plates and tables, the convenient, sterile surfaces whence humans are accustomed to taking food, there is nothing of “nature.” Kathryn never fetishizes “nature” as “untouched”; she does the opposite, working the fraught “contact zones” where not-just-humans participate in strange, physical, not entirely conceivable intimacies with one another. There is nothing at all “natural” in how consumerist societies procure and eat their prey: pigs no longer have the chance to escape into the forest while humans scramble to keep up; we no longer eat corpses, we don’t have to deal with guts and bones; that happens in the factory where animals are made and unmade, so all we have to do is sit back and enjoy citrus-marinated fillets with confit and caviar. The animal is absent from the meat even as it is the meat. The dining table is the threshold where the present-absent corpse of elided prey is absorbed by the chattering, laughing body of the idle predator. In such a setting the actual presence of “nature,” as in living nonhumanity, would be a noisy and distasteful problem.

Instead, says activist Carol Adams, “through butchering” and the apparatuses of dining, nonhuman “animals become absent referents.” “Animals in name and body are made absent as animals for meat to exist,” Adams writes. “If animals are alive they cannot be meat. Thus a dead body replaces the live animal… Animals are [also] made absent through language that renames dead bodies before consumers participate in eating them. Our culture further mystifies the term ‘meat’ with gastronomic language, so we do not conjure dead, butchered animals, but cuisine… Live animals are thus the absent referent in the concept of meat. The absent referent permits us to forget about the animal as an independent entity; it also enables us to resist efforts to make animals present.”

As if “absent referent” is a synonym for “ghost.”

I can’t resist a comparison between The Problematic Nature of Flatness and the cave paintings at Lascaux which so fascinated Georges Bataille and the radical ecologist Mick Smith. In one of the paintings, a man is prone before a bison. The latter has been disemboweled by a spear, but the man is also apparently dead. “[This] image represents the transitory vitality of human and animal lives and deaths, together with the recognition of human responsibility for the deadly consequences that the fulfillment of their desires has for other living beings,” Smith writes. The painting acts out prehistoric humans’ awareness of the hunter-prey relationship between them and their food. They knew what dining and farming industries allow us to forget: the procuration of food as a body-to-body confrontation between two living things, both with their lives at stake; the mysterious ways in which the bodies, lives, and deaths of human and nonhuman beings are “entangled, twisted together.” What a chilling contrast is the dining table with its edible squares, stripes, and circles.

The empty table in Problematic Nature is part of the equipment that conceals the hunter-prey relationship to the point of elision and a figure for the absence of that relationship, a materialization of the rift between hunter and prey in consumer cultures. It’s silent and uninscribed, this plain table, masquerading as the least forceful element of the artwork when in fact it’s the most insidious. Every dining table is a dissection table where nonhuman insides are bared and ripped with knife and fork, consumed. It’s the public side of the kitchen table, the kitchen table being akin to an undertaker’s table, making damaged dead bodies look good enough to eat. It’s the site of consumers’ conspiracy with capitalism to conceal what consumption actually entails. Even as the bodies of consumer and consumed become one and the same entity, the industrial artifices and aesthetics of dining permit us not to know it.

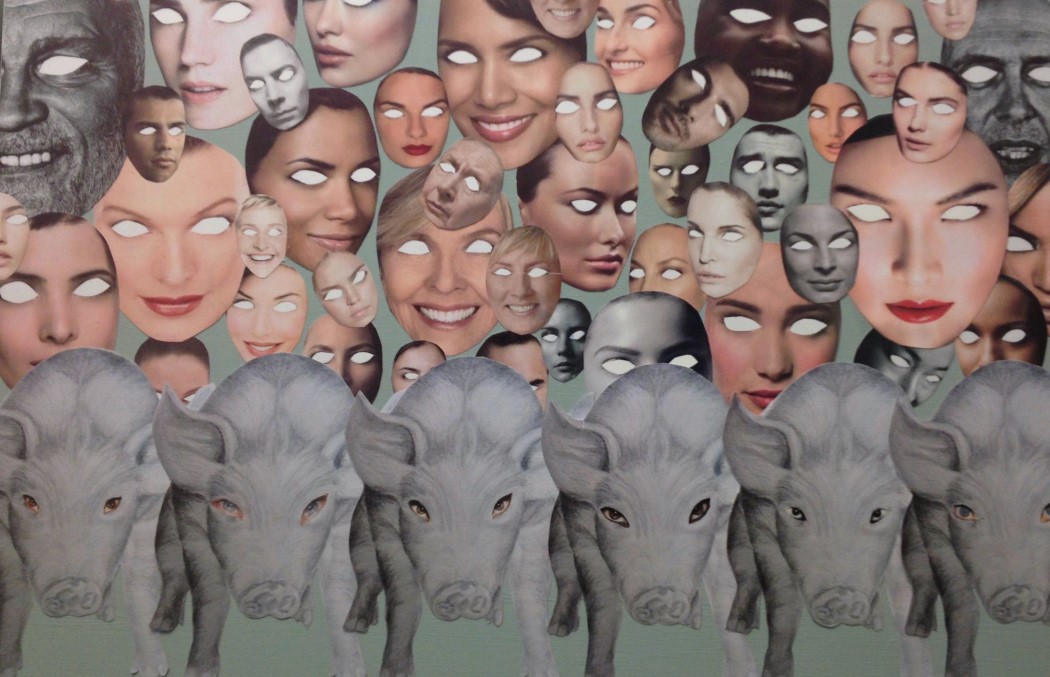

The dining table is the stage of an ideological fantasy wherein a glance across the table alights inevitably on some version of ourselves; “everywhere we look, we see ourselves” is the unspoken goal of capitalist hegemony. “We live in a society,” Kathryn writes, that is “obsessed” with looking at itself, looking especially at idealized versions of ourselves which seem somehow to represent wealth; “an obsessive fashion voyeurism,” Kathryn says, of which the flipside is “blindness” to the real living existence of those whom avarice deems worthless even as our wealth fatally accumulates at their expense. For her collage triptych, Pig Blindness, a powerful effort to “reverse the gaze,” she dismembered hundreds of pop-culture and fashion magazines, snipping the eyes out of celebrities’ and supermodels’ photographs and with a nip-tuck giving those eyes to pigs. A swarm of eyeless human superstars sweeps in a huge decaying-audio-wave formation through the first panel of the triptych right into a pig’s ear. This is a life of unacknowledgment, of never being asked, never being credited with response-ability, not even with a look: this tornado of obliviousness roaring into elongated bristle-hairy ears, and so it is the pigs who turn—to look at you. In the triptych’s ensuing panels, pigs look this viewer in the eye. Tell this human just by looking: their blindness doesn’t cut both ways.

Kathryn wagers that becoming aware of our blind spots may be a first step to overcoming them, which we may in part accomplish by deliberately listening beyond ourselves. The Problematic Nature of Flatness calls out apparatuses of blinding; spotlighting and provoking not dazzling displays of wealth but ubiquitous and subtle blinkers such as quietly reported dividends and ordinary dining tables. As a site of inclusion and exclusion (I take meat and veggies into my gullet but exclude animals and plants from my consciousness), the dining table is what’s called a zone of exception in Giorgio Agamben’s philosophy. A zone of exception is where a sovereign power declares an exception to its own laws against violence and killing, first because the victims in question are considered apolitical, subhuman, disposable beings (bare life: turkeys, cabbages), and second because the reasons for the violence are considered vitally important (my babies and I are hungry).

Nonhuman-animal voices are material vitalities whose potential for beauty is often overlooked…

Kathryn seems to understand the contradictory, obscure, half-empty, half-infinite threshold between nonhuman animals and the humans who eat them as both an ideological problem and an existential necessity. The assumption that it’s possible to excise this threshold or rift—the assumption that nonhumans can be fully understood and that to translate them from complex beings into useful goods is to understand all there is to know about them—follows the misconception that animals are resources. So Kathryn strives to maintain the rift while creating a “contact zone” where nonhuman animals present themselves in such a way that their bodies touch, stir, and disturb our own. She does it by swarming the table with sounds.

Animals’ sounds are vibrations of the animals’ insides that are and are not those insides; the timbre of a sound depends on the form of the sounding body, so the animal is materially there in its voice, nevertheless it’s clearly not reducible to its voice. Neither is an animal’s sound reducible to its voice, to the animal itself, or to what we think we hear when we hear the sound. In an animal’s sound are the presence and absence (ghost) of the animal. Kathryn accentuates the latter, the absent referent’s absence, by including no real animals or pictures of real animals in her installation, leaving us to guess which animals we’re hearing. And though these animals speak and sound emotions, we can’t presume psychological categories designed for humans by humans will suit these other beings. Problematic Nature preserves that gulf, that difference, so that you never know what you’re hearing even when you guess where the sound comes from.

Unlike a barbeque-glazed nugget, an animal’s voice is its selective presentation of itself. Yes, Kathryn’s soundtrack is artificial: she selects the animals, digitally isolates their voices from ambient sounds, and arranges them quasi-musically. But the assumption that grounds her artistic interventions isn’t that nonhuman animals are equipment. Instead, she assumes nonhuman-animal voices are material vitalities whose potential for beauty is often overlooked because we can’t quite tell what they are or what they’re doing even when we know they’re sound-of-chicken. That’s what categories do; only our categories fail on the thresholds of a chicken’s mind and heart and of the sound itself, cluck!, an entity and an expression for which there are no synonyms.

So Problematic Nature is a simultaneous performance of two clashing ideologies: capitalism and radical ecology. In radical ecology, nothing is reducible to a resource; in capitalism, everything is. At Kathryn’s table the dissembling, calculable flatness of capital meets the invisible, resounding who-knows-what of radically untranslatable individual vitality. She wants to make that friction a physical experience, something we can feel somewhere deep in our bodies—because we are diners with a choice.

From the dining table shadowed by the pale glow of the kill counter, I hear birds, pigs, cows, sheep not being there. Which means I hear their deaths. Sounds are also traces of the lives, sufferings, and potential whence they come. But that’s not all they are. Sounds are also just themselves, and traces are not only audible. I could choose not to see beyond the menus, whose message is that agribusiness generates income and jobs for humans. The rifts of willful misunderstanding and inevitable mistranslation are drawn out from behind their veils and thrown into our faces as Kathryn summons sonic ghosts which nonhuman animals leave behind in their absence.

There are so many layered lacunae in Problematic Nature that absence is an oppressive presence in it. The rift between humans and the nonhumans we eat. The rift between consumption and consciousness, perception and knowing. Between oneself and every other: the rift. Between oneself and oneself.

Interrogation Table

The Problematic Nature of Flatness wears a thin veneer: “a title,” Kathryn says, “ambiguous enough to sound interesting but not descriptive of the actual content. I have found that factory farming is not an easy topic to engage the art seeking public, so if I could get them into the room, perhaps they might stay and listen.” It is a lure, that title. It makes you think you’re here for something with white light, geometric shapes, monochromatism, paper and prostrate perspectives; something meant to show that flatness is never flat but deep and that means something complimentary about the depths of the human spirit. You enter the room expecting something safe and affirmative when in fact Kathryn’s title mobilizes the rift between humanistic concepts and the actual, bleeding subject of the piece, drawing you unawares into the chasm.

The installation forces you to admit your complicity in what you see… This is a summons, interrogation, and confession…

Dining set: safe enough. Chairs provide somewhere sensible to sit, the table designates a configured area for convivial congregation, numbers on the wall like a TV ticker tape; it’s a welcome change from the cage and cold outdoors. But sit down and screams and moans hem you in from every corner, stalk you if you change seats. Fourteen minutes of this Kathryn asks you to endure, knowing “the average time a viewer spends in front of a painting or sculpture is seven seconds.” You’re more fixture than visitor, more apparatus than audience. Rooted to your spot—the sounds beseech you to stay—you respond to the summons with confusion: menus, numbers, noise, table… how does it fit together? And then perhaps, as alien sounds invade the haven of the dining room, a menagerie stampeding the orderly center of nutritious family life, you wonder what one has to do with the other: what does this have to do with me? You look at your plate, at your menu in disguise, and you see that it has everything to do with you because you eat. The installation forces you to admit your complicity in what you see, the numbers; what you hear, the shrieking lamb; and what surrounds you, the dissembling apparatus. This is a summons, interrogation, and confession where the absence of crime-scene images speaks volumes.

You start to wonder if you were safer in the cage. Now you’re inside but exposed: you can’t look away from sound. Sound invades your body with the touch of a stranger. And in Problematic Nature, the sound is recorded, its original producer absent. Absence invades: you are exposed to the absent other’s vulnerability. Exposed to the numbers that result from what you eat as agribusinesses’ vital and mortal statistics are exposed. “The concept of exposure here is crucial,” says Ron Broglio, who works in animal studies, “a physical exposure that haunts all that happens to the animal body.” Kathryn and her audiences “risk a certain fragility in their opening . . . to the spaces of the nonhuman.” They risk “the social discord” which may attend the undermining of a profitable industry that coasts on the human right to nourishment and life. You risk exposure to the internal discord wrought by Kathryn’s summons, interrogation, and confession.

There are other people who use aestheticized sound to coerce questionable admissions of complicity. Some of those people belong to the US military. The technique is music torture, and one of its venues is the Guantánamo prison. There, as in Kathryn’s dining room, artistic sound is deployed as a forceful impact and invasion of human bodies with the aim of making “detainees” admit that they’ve done wrong. “As my work often walks a fine line between art and activism,” Kathryn says, “I also wanted to detain my audience for long enough to make an impact, which is something that does not always happen when showing visual images of animal abuse.”

Don’t misunderstand. Kathryn Eddy is no torturer. She’s an activist for human victims of domestic violence too. And while she uses sound’s physical and emotional forcefulness to encourage us to change our minds, no human animal involved in Problematic Nature is at any risk of physical harm. Kathryn risks association with music torturers’ ilk for the sake of the nonhuman animals who really do suffer. Braving the ethical limits of art, she takes her chances with potential critics.

I’ll say it again: Kathryn Eddy wants nothing to do with sound weaponry and music torture; she courageously risks that association in the interests of animal activism while demonstrating that humans in general are in fact insulated from the violence we inflict on nonhuman animals. For the most part, Kathryn shelters viewer-listeners from that violence—but not entirely. The cage is a strong hint at the high level of empathy Kathryn hopes to cultivate between her audiences and the animals we eat. The concealment of the animals’ transition from living bodies to abstract cutlets is foremost among the issues which Kathryn’s installation aggravates. But so is our exposure to an interrogation that reveals our role in that concealment.

So yes: our comfort level inside Problematic Nature is ambivalent. Kathryn manipulates it. We have the lure of the title, the dining room, a quasi-musical soundtrack with a symmetrical structure that begins and ends with the peaceful twittering of birds: all very comfortable, definitely art. The implication is that activism and nonhuman animal voices can conform to traditional notions of beauty and comfort; coexistence with nonhumans as beautiful living beings, not edible resources, isn’t such a huge leap from aesthetic appreciation and self-interest. This to me is what Kathryn’s saying: she’s not asking a lot. At the same time, her installation is embroiled in all sorts of dissemblance and relies on role reversals which would appall a humanist.

Conference Table

In Kathryn’s ideal scenario, Problematic Nature and its nonhuman participants (animals, sounds, table, numbers) elicit from their human audiences discursive sounds of confession, confusion, and questioning. They are the performers: animals and things. Visitor to the dining room, I am the instrument. But the converse is also true: they remain vulnerable to me. On such vibrant instruments I play the convoluted fugal dissembling processes of capitalism. In turn, they make me sing my own exposure. I am, yes, objectified, instrumentalized, commodified, as the installation appropriates me into one of its components, an apparatus. “You are an active part of the work,” Kathryn says. Active, yes, but part. As in gear and cog, mechanism. As an agent of de-anthropocentrism that undermines any claim of human sovereignty over other beings, challenging our right to a state of exception and hurling a rock into the great whirling engine of the anthropological machine, Problematic Nature cannot be outdone.

There’s more to nonhumans than anthropology. And because we’re only human, we can’t ever really know what more-than-human is.

“Anthropological machine” is Agamben’s term for conceptual apparatuses that insist again and again on an abyss of difference between nonhumans and humans. The machine functions ideologically, seeming to excuse the segregation, exploitation, and genocide of those thought to occupy the nonhuman side of the divide by depriving them of any political voice. In Problematic Nature, nonhuman animals instigate discussions about their own fates. Their sounds make their listeners resound with questions which continue after the lapse of fourteen minutes in discursive spaces beyond the gallery. As Problematic Nature throws up the hood on hardware which encourages misconceptions of human animals’ relationships with the nonhumans we eat; the ghosts of the nonhuman, their alien voices, and the hermetic traces of their passing revitalize the dining table, transform it from a site of dead-meat consumption into a catalyst of lively discussion. “Over and over again, people sat down at the table and stayed,” Kathryn writes. “Some started discussions with friends and strangers across the table.” The table itself summons awareness of what goes on around it and why it was made.

But it’s not just about discussion. Problematic Nature is about eating and listening as other ways of making contact which are perhaps loosely analogous to archaeology. If archaeology is a quest, via exposure to too much light and dirt, to bring nonhuman things into contact with our surfaces, then Kathryn excavates ghostly sounds of prey animals from the dust of their dissembled absence, bringing her guests into a strange kind of contact with nonhuman animals themselves; physical contact, closer than close, across the infinite thresholds of time and death. But the risk of “archaeological rhetoric,” says archaeologist Bjørnar Olsen, is misconstruing excavated things as “a means to reach something else, something more important—cultures and societies: the lives of past peoples, the Indian behind the artifact,” as if nonhumans are just human expressions, “mirror images of ourselves and our social relations,” so that archaeology amounts to nothing more than a look in the mirror.

Kathryn Eddy loves to say, “Some things are untranslatable. And I’m okay with that.”

The same goes for critique. Critique is necessary; we must excavate the ideologies that determine physical forms: cow becomes steak because of capitalism, four-legged plank masks a dissecting-dissembling machine because humanity thinks it is above blood and guts and tries to drown out with vanity the speciesist delusion that inspires anthropocentric vanity! But even this amounts to humanistic translation—the human(ism)s behind the de foie gras—and there’s more at stake than that. There’s more to nonhumans than anthropology. And because we’re only human, we can’t ever really know what more-than-human is. Kathryn Eddy loves to say, “Some things are untranslatable. And I’m okay with that.”

Critique is at the heart of Kathryn’s work; but so are affirmations of the inexplicable material beauty of animal voices, the contradictory potential of the dining table as a space for discourse and interrogation as well as comfort and consumption, and the wonderful inexorability of the rift between consciousness and the untranslatable. Kathryn’s many-sided table is a material site of the rift. Through sound, Problematic Nature makes contact with nonhuman animals while preserving the distance that makes them irreducibly other. So this “contact zone” is also an unbridgeable ravine; despite its critical potential as the openness of questioning, the rift is simultaneously a terminus: it’s the last stop for slaughtered nonhuman animals and a dead end for thought. On the far side of the ravine, Agamben says, nonhumans exist in “a zone of nonknowledge” for humans. Each nonhuman “stands serenely in relation with its own concealedness” beyond the rift. Sounds are shimmering contact zones which make possible a fleeting, “surface” understanding of themselves and the things who make them; but simultaneously these same sounds are too distant and too bound up with our own bodies to afford any decryption of the kind that could masquerade as knowledge.

This is an extract from Listen, we all bleed, a brilliant new collection of essays and other texts by Mandy-Suzanne Wong, published by New Rivers Press, November 2021.

This is an extract from Listen, we all bleed, a brilliant new collection of essays and other texts by Mandy-Suzanne Wong, published by New Rivers Press, November 2021.

You can order your copy direct from the publisher.

Published here as part of ROT, a section of The Learned Pig exploring multispecies creativity through modest tales of collaboration and coexistence amidst world-ending violence and disorder. ROT is conceived and edited by Julia Cavicchi.

About Kathryn Eddy

Kathryn Eddy is an interdisciplinary artist who uses painting, drawing, collage, photography, sculpture, writing, and immersive sound installation to explore the complexities of the animal/human-animal relationship. As an activist against racism, domestic violence, and animal abuse, her work explores linked oppressions and examines the patriarchal power structure that perpetuates them.

Her immersive sound installations, include often overlooked animals and their troubled and abusive relationship with human animals.

She co-founded, along with artists Janell O’Rourke and L.A. Watson, ArtAnimalAffect, an artist coalition dedicated to bridging art and activism within the field of critical animal studies. In 2017, they organized and participated in The Sexual Politics of Meat Exhibition at The Animal Museum in Los Angeles, Ca. A full color catalog entitled, The Art of the Animal: Fourteen Women Artists Explore the Sexual Politics of Meat, was published by Lantern Press.

From January through March, 2020, her current ongoing immersive installation, Urban Wild Coyote Project, was exhibited in its entirety for the first time as part of the exhibition, Animals Across Discipline, Time, and Space at the McMaster Museum of Art in Hamilton, Ontario, curated by Dr.Tracy McDonald. A full color catalog was published, co-written by Mandy-Suzanne Wong.

www.kathryneddy.com

Image credits (from top):

1. Kathryn Eddy, Pig Blindness (detail), 20×30, pencil, paint, collage on wood, 2014

2. Kathryn Eddy, The Problematic Nature of Flatness, outdoor installation (day), variable, 2012-ongoing Photo Credit: Patricia McInroy

3. Kathryn Eddy, The Problematic Nature of Flatness, outdoor installation (night), variable, 2012-ongoing Photo Credit: Patricia McInroy

4. Kathryn Eddy, The Problematic Nature of Flatness, indoor sound installation, variable, 2012-ongoing

5. Kathryn Eddy, The Problematic Nature of Flatness, What Happened to Your Lamb, Clarice?, 18×24, acrylic paint on canvas, 2012

6. Kathryn Eddy, The Problematic Nature of Flatness, Plastic Pigs Can’t Scream, acrylic paint on canvas, 2012

7. Kathryn Eddy, Pig Blindness, 20×90 pencil, paint, collage on wood, 2014

8. Kathryn Eddy, Pig Blindness (detail), 20×30, pencil, paint, collage on wood, 2014

9. Kathryn Eddy, Pig Blindness (detail), 20×30, pencil, paint, collage on wood, 2014