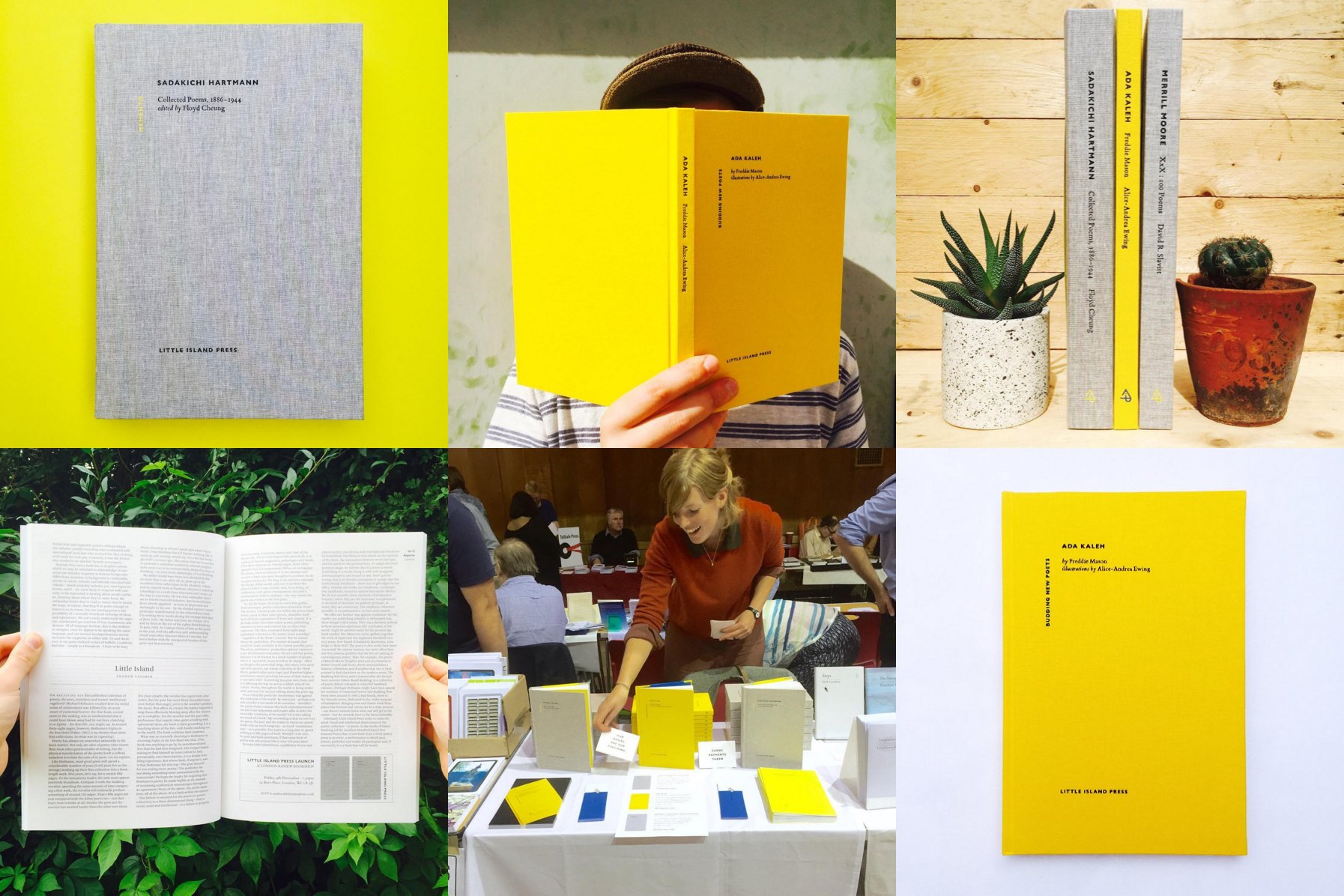

Little Island Press is an independent publisher of new and classic poetry, fiction and international literature in translation. Inspired by some of the amateur presses of the 1920s, Andrew Latimer founded Little Island Press in 2015. Its output spans three different series: Memento, which presents the work of overlooked modern poets; Transits, which offers poetry in translation; and Budding New Poets, a series focusing on innovative new works by emerging poets. It is from this last series that we chose our book of the month for November. Ada Kaleh pairs the poetry of Freddie Mason with the illustrations of Alice-Andrea Ewing (whose porcine busts graced The Learned Pig in 2015). It is an incredibly beautiful book – not only Mason’s words and Ewing’s images but also in terms of the book itself as a precious physical object. This is characteristic of Little Island Press.

With a launch event taking place at the London Review Bookshop on 4th November, we spoke to founder Andrew Latimer to find out more about the material beauty of books, the ethos behind his work, and his plans for the future of Little Island Press.

First up, could you explain the name – Little Island Press?

The ‘Little’ part of the name harks back to the so-called ‘little magazines’ of the early twentieth century. Despite readerships of sometimes less than a few hundred, these tiny magazines were the breeding ground for some of the last century’s most influential works of literature. I allude, most obviously, to the serialisation of Joyce’s Ulysses in The Little Review from 1918 onwards. On top of this, these magazines were emphatically international in outlook. Several of the American quarterlies had European editors whose job it was to ensure that the transatlantic cultural connection remained intact – not an easy job in the days before instantaneous communication.

By choosing the name Little Island Press I hoped to borrow something of the intrepid internationalism from these wonderful but sadly now-extinct microenterprises. Having already published three books by American authors, with two more in progress, as well as two translations from Estonia due in 2018, we are very keen on ‘trading’ culture beyond the national level – importing and exporting the best literature from the once significant but now little island that is Britain. The name has taken on some interesting new weight recently!

Straight away the thing that strikes me about your books is the design – clean and minimal with striking colours, but also very tactile with the cloth cover. Could you say a little about why this aspect of books is important to you, and also a little on the specifics with regards to choice of fonts, paper and colours?

‘Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.’ These are the alleged words of the bizarre aeronaut-author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Apocryphal or not, this mantra has served as something of a guiding light for the creation of the Little Island Press books. Take, for example, the front cover. It presents the bare minimum of bibliographic information – title, author, publisher and series. No embellishment whatsoever. Remove one aspect of these four ‘grid’ areas and the delicate structure crumbles. And the vast space in the centre of the cover, the space usually filled by some largely irrelevant glossy photograph, instead puts the reader in direct contact with the material from which the book has been made. It invites you to touch as well as to look.

Why is all this fussing important? Well, I used to work next to a book-recycling factory. A very literal example of the limited shelf life.

An important part of establishing this simplicity was to strip the format of the book of any unnecessary elements. For a hardback, this meant doing away with the dust jacket. I have always found these a bit of a hindrance, and usually end up removing them from my own books and storing them in a pile out of sight. Instead, we replaced the traditional dust jacket with a bellyband that holds the same information like blurb, barcode and price. We fully expect our readers to throw this band away once they get the book home and enjoy the simple tactility of a hardback book.

One of the main sources of inspiration behind the whole house book design was a handful of New Directions ‘Poet of the Month’ pamphlets from the 1940s, a series of poetry pamphlets commissioned by James Laughlin whereby each pamphlet was printed by a different small press in America. What a lovely idea! The pamphlets are so understated, almost utilitarian. Our layout, the careful deployment of typography across a given space, is a modern take on that old idea. The introduction of the second complimentary typeface, Gill Sans Nova, however, harmonises with the much more traditional Bembo Arcadian type and brings the whole look up to date. This interaction between the two typefaces is then played out across the internals of the book as title and text.

As with the fabric covers, the type of paper was very important to the overall design. Firstly, it had to be weighty. Poetry books, by their very nature, produce a lot of white space. More often than not when you read a page of poetry you are actually reading several poems at once, as they all lean into the space that should be white. This is commonly known as show-through, and is less of a problem in prose books where the text covers most of the page. Our stock, a heavy Munken Lynx, prevents this almost completely. Coupled with its pleasant just-off-white tone, the paper creates a very pleasant reading experience – the antidote to the computer screen.

Why is all this fussing important? Well, I used to work next to a book-recycling factory. A very literal example of the limited shelf life. My hope is that people will want to hold on to our books through time because of the attention to detail shown in every aspect of their construction.

Where are the books printed and made?

I’d be lying if I said that the production of our books has been plain sailing. We initially tried a printer in Wales whose quality of printed product was superb, but the standard of foil-blocking on the covers wasn’t good enough. The small font size mixed with the roughness of the material caused them problems, as it did a number of other printers. We shopped around the UK – almost every printer, I’d say – to be told that either they couldn’t block the covers or that it would cost too much. We were disheartened, and considered altering the design completely. Then we found Graphicom in Vicenza, Italy. They print a lot of UK art books and cookery books – genres with generally higher production values than poetry. They did us a few foil samples and then we were away. We’re really happy with what they’ve achieved so far, but certain recent events have put the future production of our books with them in jeopardy. No doubt we’ll be looking to have them printed in the UK next year. This seems the safest way forward for us given the enormity of the unknowns ahead.

There now seem to be a few independent publishers emerging with a focus on producing beautiful books. I’m thinking of, say, Corbel Stone Press, Fitzcarraldo Editions, or Slightly Foxed. Do you see yourself as part of a larger movement or community or are you ploughing your own furrow?

I think the important thing to notice about the publishers you mention – and I’d add Notting Hill Editions to that list – is that they all have a very pronounced house design style, or brand. You pick up A Primer for Cadavers or Mentored by a Madman and you soon realise that you’re not just buying one book, you’re buying into a collection, a series of books with a collective aesthetic identity. In this respect, these publishers are acting more like micro-galleries than traditional publishing houses; they deliberately present an ever-expanding exhibition of written pieces that continue to interact with one another.

For me, poetry is as much a visual art as it is intellectual or aural. For this reason it has always been frustrating that many poetry books are so poorly produced.

These publishers are acutely interested in the book’s physical presence in relation to other books, perhaps even their relation to other non-book objects. They are deliberately foregrounding the book as exactly that: the book – a physical thing of this world that was made as well as written and intended to be held as well as read. Most likely it is a reaction against the threat posed by the digital as it seeps into our lives. But the appeal, and the result, is timeless.

Whilst Little Island Press has much in common with these other publishers, I’d say that we are perhaps the only publisher currently doing what we do with poetry. For me, poetry is as much a visual art as it is intellectual or aural. For this reason it has always been frustrating that many poetry books are so poorly produced, so visually unappealing. Of course, poetry publishers are limited by the price their books can fetch. We are trying to gradually expand the bounds of those limitations, out of a respect for the genre itself as well as for the exciting poets and projects we have on our list.

Ada Kaleh – our book of the month this November – pairs the poetry of Freddie Mason with illustrations by Alice-Andrea Ewing. Was this your idea, and if so why? Is the pairing of illustration and poetry something you plan to continue with? What are the difficulties with doing so? How do you think the two complement each other – both generally and in this specific case?

Ada Kaleh appeared as the complete product, as if out of thin air. Freddie (poet) and Alice (artist) are friends and had been working on the project together for a while. I think this is what makes it such a special piece – that the illustrations and the words arrived together organically. The interaction between the two mediums takes place on a much more meaningful level than the purely literal – as might be the case in a more straightforward picture-text book. You see themes, tropes and motifs emerge in the drawings that are mostly submerged in the text. I suppose most readers will think of it as a poem with illustrations, which makes sense, but I don’t think it would be absurd to conceive of it as a set of illustrations with accompanying poems. Such is the level of the two mediums’ interdependence. Freddie was also very keen to establish Alice as a co-author, inviting her to comment on layout and book design as well as splitting the royalties 50/50.

Since publishing Ada Kaleh we’ve had a number of people approach us interested in collaborations between literature and visual art. We’re always open to these kinds of projects. But I’d always be wary, however, about foisting artwork onto a text that either doesn’t need it or simply doesn’t have the conceptual space for it. This creates a hierarchy – usually text to picture – that makes the illustrations into an appendage to the text. If we do more illustrated books in the future, I’d be keen to follow in the vein of the egalitarian collaboration model brilliantly set by Freddie and Alice in Ada Kaleh.

What first sung to you about Ada Kaleh? What do you look for in an early-career poet?

In terms of a piece of poetry, Ada Kaleh is a veritable storm in a teacup. From beginning to end there is very little let-up. It ranges an impressive array of matter in relatively few words; each word, it is clear, has been shaped, tested and (reluctantly) allowed to remain by the poet. From a specific ‘poetry’ point of view, I was impressed by the way in which Freddie had assimilated and moved beyond the influences of Beckett and J.H. Prynne. I had very little work to do in terms of editing. Each time I tried to intervene, the manuscript resisted.

The Budding New Poets series is particularly interesting to me because it presents book-length collections by first-time or early-career poets. Unlike other new poets series such as the Faber New Poets series, which presents the best work of new poets in pamphlet form, the Budding series asks poets to also think about the unity of their own work and how it might come together to form a collection. Of course the primary emphasis is still on the integrity and fluency of the individual poem – that cannot be overlooked – but going beyond the string of well-written poems allows poets to consider what might make the whole collection an interesting book to read. And this inevitably feeds back into the way they conceive the individual poem.

Ada Kaleh has its illustrations and the thematic recurrence of flooding and memory. The next in the series, Extravagant Stranger by Daniel Roy Connelly, is structured like a memoir, which has its own confessional and digressive structure. So, beyond an innate articulacy and an interest in poetic form, I usually look for a poet with an interest in how poems come together to make a book.

The Transits series looks really intriguing. Why was it important to include this strand in your publishing programme?

Translation is such a difficult and rarely acknowledged art. Why anyone would commit their valuable time and energy to such thanklessness is beyond me. But some do, and I am grateful. Part of the reason why good translation is so rare is that it relies on the consonance of two different artists – one of which has to be almost wholly selfless. On top of this, to translate poetry, the selfless artist also has to be a poet of technical skill – and it certainly helps if they are also an amateur biographer, psychotherapist and linguist.

Translation is such a difficult and rarely acknowledged art. Why anyone would commit their valuable time and energy to such thanklessness is beyond me.

Our Transits series is a modest attempt to add a few more quality translations to the Anglophone literary world. In particular, our emphasis is on literature from nations that have been ignored. Estonian, for example, is a difficult Uralic language. For this reason, among several, many of Estonia’s best authors and poets have been refused the renown and respect afforded to their European contemporaries. With the help of a few esteemed translators from around the world we hope to rectify this situation.

How did you make your selection for Memento? Was it based on personal preference or some other criteria too?

I suppose the selection process always begins with personal preference. But there are so many events that intervene along the way: rights, archives, literary executors, heirs, libraries, budgets. The series would have been about ten times longer at least had I been given free reign from start to finish. What the Memento series constitutes now, after its first batch of five poets, is a collection of twentieth-century poets that deserve a proper second look. In the words of editor David R. Slavitt in his introduction to the exquisite poetry of Bink Noll: ‘Noll’s obscurity in the poetry business isn’t his misfortune but ours’. Some, like Sadakichi Hartmann, plug important holes in the birth of American modernism. Others, such as Lola Ridge, provide vital female counter-narratives to largely male-dominated experiences of the modern city. But, in the end, I suppose it comes back to personal preference, for they are all poets that I still enjoy reading.

What are your plans for the future of Little Island Press?

Our transatlantic program continues. This year (2016) was about bringing the US to the UK – quite literally as two authors travel from the East Coast to read at our press launch at the London Review Bookshop on 4th November. Next year we hope to take Little Island to America. We’ll be releasing all of our titles in the US next spring, and we hope to accompany their publication with a press launch in New York.

Next year will also see our first foray into the world of fiction: a collection of stories by the esteemed writer, editor and literary pedagogue Gordon Lish. White Plains, as the book is to be called, is a stripped-back excursion to the peripheries of the literary monologue, packed full of Lish’s characteristic humour, satire and indefatigable humanity. We hope it will be a success for Lish, garnering him an even larger and well-deserved readership on both sides of the Atlantic as he enters his eighty-third year.

There are, of course, big plans for Little Island Press – including a bookshop with events and residencies, mentorship schemes and more – but right now it’s all about surviving. There are a host of challenges ahead, many of which we haven’t even thought of yet, and for now it makes sense for us to be and remain little.