The inaugural Helsinki Biennial planned for 2020 was postponed, like so much else. Finnish artist Jussi Kivi has explored the maritime Biennial site – an archipelago island and former military base, Vallisaari – even more extensively for his installation than its resident badgers have for their setts. Kivi is an explorer in the best sense of the word: curious, practical, generous, visionary. An abundant sense of humor and humility seems hitched to Kivi’s sketchbook, camera and walking boots. He roams and often returns to edgelands, forest, tunnels, and military and industrial landscape ruins. Short-term gains of extraction mark the places Kivi comes to know, whether road-cut Finnish forests or abandoned mines. His experiences are shared as offering, meditation, provocation, requiem of our landscape’s losses, and reminder of the essence held in the remains.

Kivi is a visual artist who won Finland’s prestigious Ars Fennica prize in 2009 and represented Finland at the Venice Biennale in the same year. His home and studio are in Helsinki, while his research and exhibitions have stretched beyond Finland and Scandinavia since the 1980s. Kivi’s photographs, drawings, maps, scale-landscapes, dioramas and collections of found objects – with their twinned, intimate expression of destruction and integrity – dissolve boundaries. At opposite ends of a summer day, between Vermont and Finland, I visited with Kivi to learn more about his mapmaking.

How did you begin making maps?

I started making maps in the early 90s. I was inspired by the old maps, old hand-made maps. I’ve always been a little interested in maps. When I was young, I read these adventure books where the guys went somewhere in the forest or backwoods, and sometimes there was a map in those books, treasure maps and things like that.

When I was a kid, I had a city of Helsinki map on the wall beside my bed. I also spent a lot of time in a fire station near where we lived and they had a city map there, so I also wanted to have it on the wall.

Somehow by chance I started to draw a map. It was maybe 1990 or 91, and I had just started teaching in the art academy in Helsinki. We had some kind of teachers’ meeting and it was boring, so while the others were talking I started to draw a map. I drew from memory a map of a trip I’d taken with a friend to a new place; we’d had a nice time.

Somehow by chance I started to draw a map. It was maybe 1990 or 91, and I had just started teaching in the art academy in Helsinki. We had some kind of teachers’ meeting and it was boring, so while the others were talking I started to draw a map. I drew from memory a map of a trip I’d taken with a friend to a new place; we’d had a nice time.

I soon realized I couldn’t make maps only from my memory – they were too simple. I also like geographical and topographical forms, so I started to use real maps as source material. But I always make maps from some place I’ve been that is interesting. They’re also a kind of travel diary for me. I do them after the trip. I might do some sketches at the site, but mostly I draw them at home.

I only make artistic maps – I don’t measure very often or things like that. It’s a visual thing. I’m quite used to maps. Once I was in an airplane in Finland, traveling from Helsinki to an east Finland city and we were going above the lake land area; there are a lot of lakes. Suddenly I saw one island that looked familiar – I thought maybe that’s the island where we had our camp on one trip. I took a photo through the window of the airplane and I compared the photo to the maps at home after the trip, and it was that place. I was proud of myself that I recognized this little tiny island where we’d had our camp maybe a year or two before. But that doesn’t always happen!

How does map-making affect your other work, or how does your other work affect your map-making?

I always do drawings of places, little pictures of places, because often there is something interesting on a site and somehow, it’s also mapping, to make a drawing of a place.

In old times, scientists also had drawing skills. Geographers, explorers, even military officers were educated to draw. A long time ago, I took a short course about archeological drawing. Archeologists often draw maps of their excavations, but they also make drawings of the objects they find. Drawing is better than photography for something like a Stone Age ax head because you can make how the stone was cut more visible, show how it was made. This drawing is a kind of mapping of an object, and that was interesting to me.

A few times I have said, “I’m not going to make maps anymore, it’s too boring.” But then somehow, I always end up mapping again. I maybe have some kind of need for it. It’s also that when I’ve been exploring some interesting place, to make a map of it is like a continuation of that exploring. I get the place in my mind more clearly.

I’ve been exploring some underground mines with friends. It’s very difficult to make a map of this kind of space. It’s a labyrinth, and there are a lot of tunnels and different layers. It’s difficult to make an image of the whole thing, so I try to make a map.

What do you feel is important for a map to include?

The structure of the place, and the topography. But I think it’s not only that – I often write things on the map. It’s one way of sharing the experience. You might take a photograph of the landscape, but I make a map.

I was recently on the island where the Biennial will be. There are old fortifications there, made by the Russians in the late 1800s. But by the time they were finished the enemy artillery had developed so much that the bunkers were obsolete. They had to make new ones, so there were already a few layers of bunkers.

Then in the 1970s, in the Cold War era, the Finnish army built new bunkers above them, yet another layer of coastal artillery bunker. And then there are badger dens. For the original Russian bunkers, they transported in a lot of white, fine sand. And sand is very good for the badger! Now there are two kinds of underground structures, the human military and the badger families living there. Even though I’ve thought I don’t want to make any more maps, I find this combination so funny that I have to make a map of it.

Have you ever found a place that defied mapping?

Not really, but some maps I haven’t shown, or I have to think where I show them. I’ve also used a pseudonym for an exhibition with maps of city infrastructure places from Helsinki and that sort of thing. So if someone asked, “Hey, have you been here?” I could say “No, it wasn’t me, it was this other artist.” My invisible friend.

Is the Finnish public access right in your mind consciously as an artist, or is it something you take for granted? I assume tunnels aren’t included.

No, tunnels don’t belong to this “Everyman’s Right,” But I think if they catch me, then I will ask, “How is it so, that Everyman’s Right is up there, but not down here?”

I don’t think about it too much. You’re not allowed to go to someone’s home or garden, you’re not allowed to go to someone’s business, so with some industrial areas it’s a little tough. If there’s a fence around and signs, then I look that nobody sees me when I go. Because they can maybe come and kick me out. But I don’t think about it very much.

Does your work or the way you want to share something in your art change from place to place or country to country?

It doesn’t change. No, I don’t think so. The starting point is always that there’s some experience from a place and I want to share it or I want to work with the experience, continue it – that’s the main thing. It depends on what I find. It might take time, that’s why I like to go again to the same place. It worked out well for this island project, the Biennale, because I had the possibility to return again and again. I was photographing there a lot, but it was ordinary photography, just take some nice photos from a nice place. But just about three weeks ago I somehow figured out how I want to photograph. I found something new for myself, with black and white photos. Now I’m a bit excited about that.

Using black and white is like a history of place. There are ruins and some wild forest on the island, so I’m trying to make photos that look a little bit ruined, or like something which you have found – not too much, but a little bit like that. I’m making an installation there for the exhibition; it’s like a scale-model landscape in a dark room. It’s a bit of work, but I’ve made a few of these kinds of forests.

Do you like to know something about a place before you go there? How do you research a place?

Of course, I want to know something. I’m searching for special spots, I don’t want to just go to a potato field or somewhere. I also have friends who do this type of exploration, so we share information and do trips together. Often it happens that when I go and have some kind of experience, then after that I start to study more about the background of the area. After I have some kind of experience with the place, and some kind of connection to the site, then I start to search for information.

The best places – there are still places where you don’t find too much on the internet. Before, I did some archive studies, and that’s also another thing that needs a lot of skill, and also luck. It’s so easy with the internet nowadays.

What is your favorite kind of place to go?

I don’t know, it depends on the place. Recently I’ve also enjoyed nature trips, to the forest, which I did before. Maybe I’ve gotten a little tired of these dark, dark tunnels. I have done a lot of it, and it seems when I take a photograph, they start to look the same. I’ve been to some extreme, weird places, but you don’t find them very often, and some of them are dangerous. If I want to continue, then I’ll have to take another step to go to more dangerous places, which I don’t want to do. My friends are doing that; they are young guys and immortal!

I’ve done a lot of that kind of exploring. If I find something then I’ll go, but I’m not actively looking for them so much anymore. I know so many places already that it’s difficult to find new ones nearby. Of course, the world is full of places, but I don’t like flying, and I don’t like to travel around to get to distant countries.

How does your awareness of climate change and a sensitivity to loss play out for you, either when you’re creating or afterward when you’re having an exhibition?

When I was younger, I had some kind of naïve idea, idealistic ideas that art will help to change the world for the better. Now that I’m just an old, bitter man (laughs) who doesn’t believe that anymore. I am quite concerned about nature, and it’s been that way since the late 70s.

When I started taking forest trips I found out that the forest industry is so dominant in Finland. It was difficult to find the kind of nature I thought would be there. When I started to make scale-model forest, there was some irony. “Ok, I make my own, because they’ve destroyed everything.”

When I started taking forest trips I found out that the forest industry is so dominant in Finland. It was difficult to find the kind of nature I thought would be there. When I started to make scale-model forest, there was some irony. “Ok, I make my own, because they’ve destroyed everything.”

Do you want people to feel any particular sense of loss or grief when they view your work, or do you think people are just going to have whatever feelings are provoked by what you’re presenting?

Yes, of course there is something that I want to show, and say, but it’s not that straight. Sometimes I feel that I want to provoke, but it’s quite a mild provocation. It’s a problem as an artist, if you’re an artist and at the same time have some kind of activist mind. I think there are some artists who have this activist way of thinking and then they try to force it through their art. And it’s boring. Or then they do some very simple art and they explain how political their work is. But what kind of political power is it if it’s in the gallery and only one person sees it? It’s not very effective politics. I’m still teaching a bit, and I’ve said to students, “You should become a politician if you want to have some effect.” Don’t have this illusion that you make some statement as an artist, that it has some meaning. Only other artists will see it, and that’s it. If they’re looking to have that kind of influence, there are more direct ways to do it, rather than have this kind of false-forcing through art. An artist must ask why they make art. Why am I doing art and not something else? I know that I wouldn’t be a good politician.

Now autumn, Kivi writes to tell me he continues to work on Vallissaari, preparing for the Helsinki Biennial in 2021. His installation, full of “technical experiments” and in an old abandoned house, will feature scale landscapes and dioramas, as well as drawings, photos, and a collection of found objects from the island. The working title is “Vallisaari Island Heritage Room and Museum of Disappearances.” Kivi explains the effort has been slow-going, with the installation’s engineering and handwork demands complicated by the pandemic:

“At first I thought that I am too slow, but then I thought about Giotto. It must have taken several years for him to make frescoes to Assisi Church, even he had some assistants. So, one or two years for an installation is nothing.”

Image credits (from top):

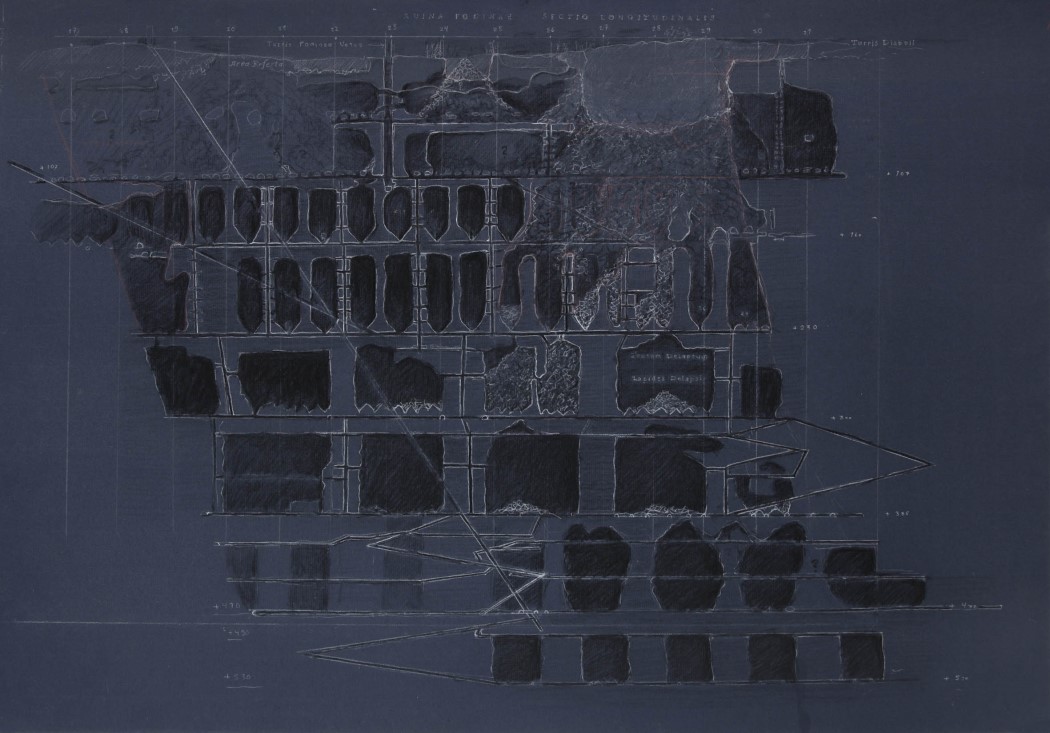

1. Jussi Kivi, Longitudal section and projection drawing of collapsed mine, charcoal, white crayons, 2019

2. Jussi Kivi, Meiko – Lappträsk – Dorgan, The uninhabited areas of Finland part 12, field studies: 1977-, the map: 1992-97, watercolor, ink

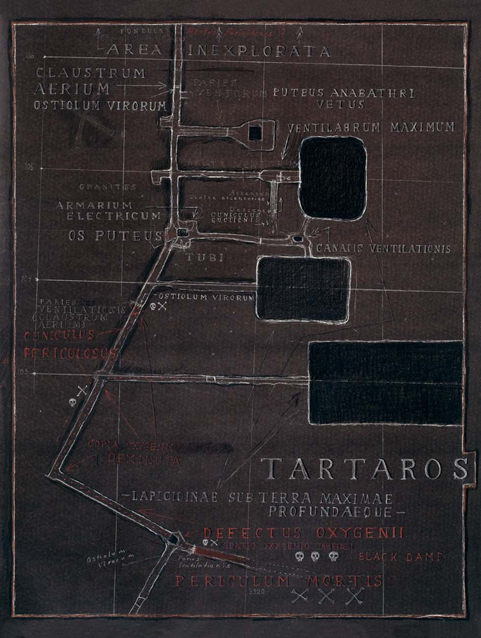

3. Jussi Kivi, Tartaros – lapicidinae sub terra maxima profundaeque, white and red chalk on tar paper, 2012

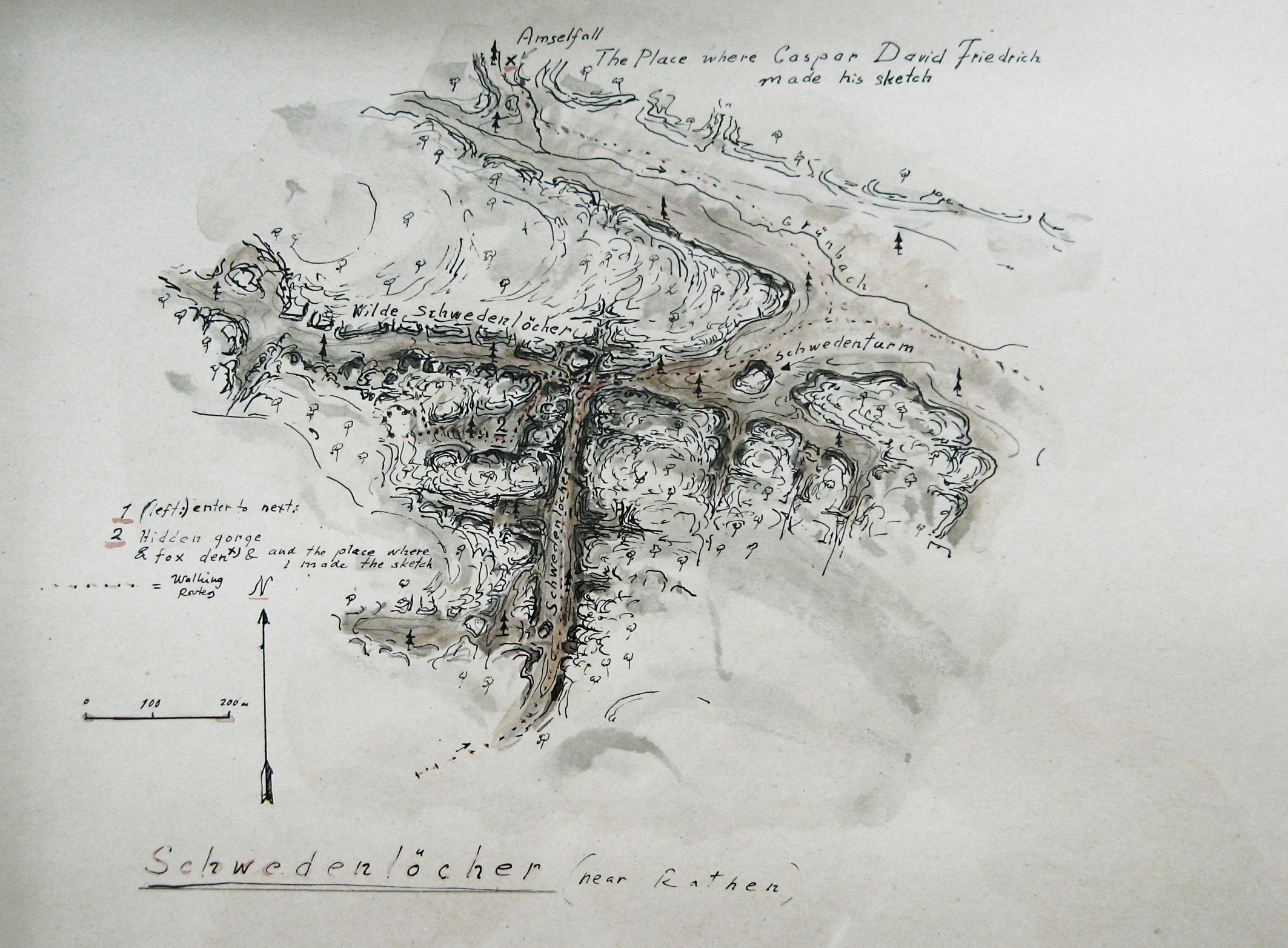

4. Jussi Kivi, Schwedenlöcher near Rathen, Germany, ink, water color. (year not known, approx 2004) Schwedenlöcher is steep gorge in Elbsandsteingebirge mountains. In 30 years war people from the local village were hiding there because of brutal Swedish warriors. Nearby there is also Amsellfall, a little waterfall where Caspar David Friedrich made his sketches.

5. Jussi Kivi, Hell’s Sink – Underground exploration map of city infrastructure tunnels and other underground spaces by Redrick Shoehart, site-specific pencil drawing to the gallery wall (part of Infiltration at Sicspace, Helsinki 2020)

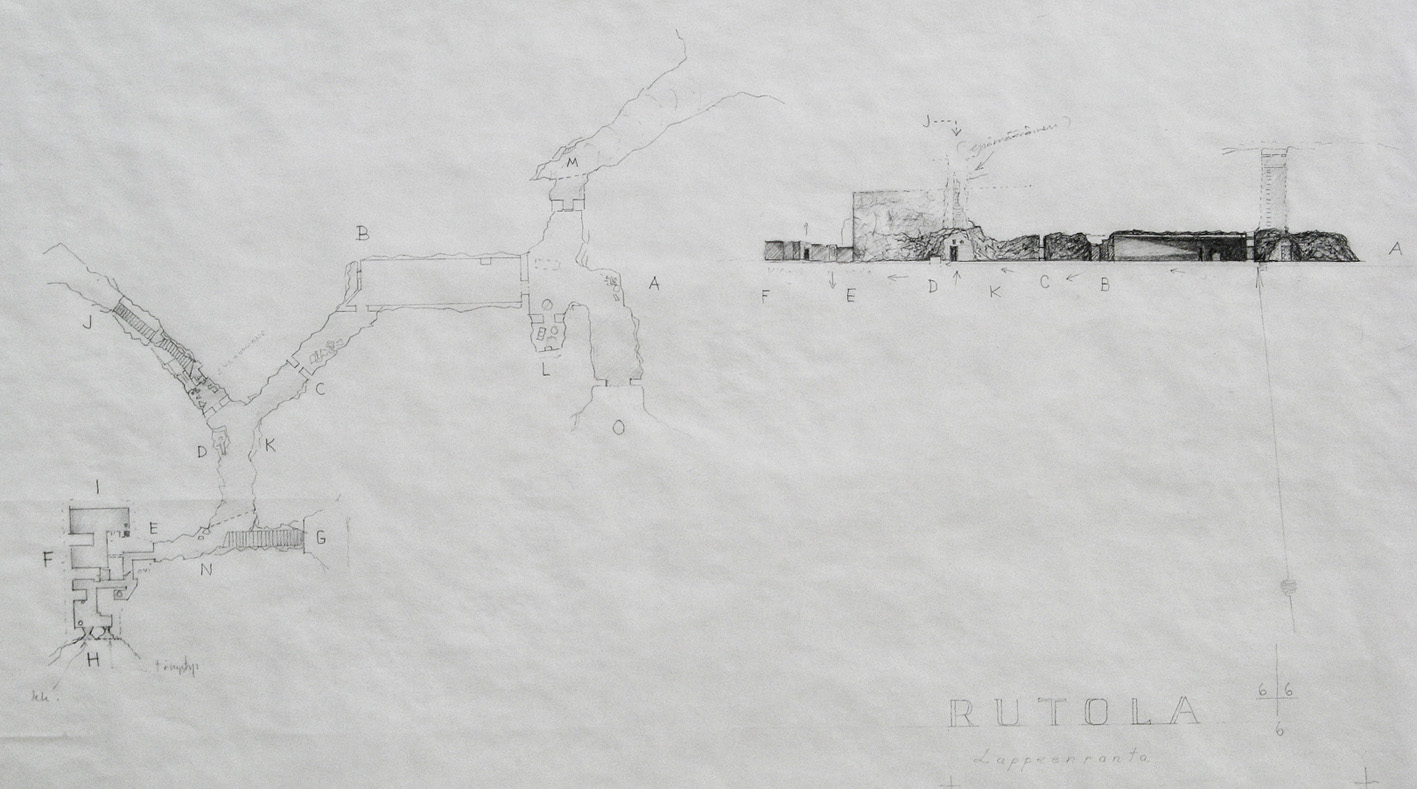

6. Jussi Kivi, Rutola, Lappeenranta, a cross-section drawing and a ground plan of Second World War era underground bunker in East Finland, pencil 2006

7. Jussi Kivi, The underground line, a map of underground night walks below the city, digital image 2019. This work is based on a pencil & watercolor drawing on The Helsinki City Transport bus & tram line map, then photographed and worked digitally.

8. Jussi Kivi, Ivalojoki-River I, shards of quartz from a prehistoric river bank camp site, Camp 15-16.9.1995, ink, crayons 1997

9. Jussi Kivi, Tartaros, map projection, stopes and upper levels

This is part of ROOT MAPPING, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring which maps might help us live with a clear sense of where we are. ROOT MAPPING is conceived and edited by Melanie Viets.