Journeys are made of stories and every traveller describes the places he has been using stories. This journey begins in the yoghurt aisle of a supermarket in Reykjavik, crosses 1300 miles of the North Atlantic, swimming with tales of sea monsters, mermaids, pirates, ghost ships, smugglers and rum to end in a cocktail bar built into the jaws of an ancient, preserved Blue Whale in Gothenburg.

Six years ago, I took part in a residency as an artist and crew member sailing from Iceland, across to the Faroe Islands and finally to Sweden. The crew, on our 22 metre steel boat, included an oceanographer and whale specialist and we aimed to document whales in that part of the ocean. I specialise in hand drawn maps and wanted to map the trip, annotating it with details of man’s interaction, both now and historically, with whales.

In Iceland, I asked local people for any whale stories they had. Whale watching was clearly big business in Reykjavik. The harbourmaster told me that some tourists went whale watching and then had a whale steak to finish the evening. Many of the restaurants had whale and dolphin meat on the menu… “Just like marshmallow…,” a waiter told me.

We set sail for the Faroe Islands. A watch every 6 hours meant rising in the middle of the white Northern night and sleeping when I was done. The sun seemed to swing around the sky, never quite dipping fully out of sight. My body was the only reference I had; ignoring clocktime and eating and sleeping when it ached. The first whales we saw were a pod of pilot whales, maybe about 30 of them, speeding alongside the boat, dipping and diving blackly through the pale, grey water. They stayed with us for a few miles before we out-sailed them, whistling to each other in the distance. Several times during the trip, I thought I heard the soft song of whales through the hull of the boat as I lay in my hammock but I must have imagined it. We saw ominously few whales or dolphins at all.

My body was the only reference I had.

In the Faroese capital, Torshavn, we were greeted with suspicion. As soon as the word “whale” was mentioned, people assumed we were protesting the hunt of pilot whales there, the Grindadrap. I interviewed from a seemingly neutral standpoint and most were keen to explain the reasons behind the tradition and how it was practised. Here the value of the whale was seen as cultural – the hunt as a spectacle for the community rather than tourists and the spoils divided up as food.

We set sail again into the endless light. In fact, the first darkness I saw was two days before trip-end. I remember standing on deck, the boat almost flying over the waves, fascinated by a single star and a huge, full moon scudded with clouds ahead of us. It was the kind of moon to make your hair stand on end.

We finally reached Sweden at the end of the month. One of my goals in Gothenburg was to visit the Malm Whale at the Natural History Museum, a Blue Whale beached and preserved in the late 19th century. At some point its jaws had been articulated and opened up so tourists could step inside. Referencing the biblical story of Jonah and the Whale, a visit was promoted as a religious experience. As time sailed on though, it became both a café and a cocktail bar, the roof of the whale mouth draped in blue star-spangled silks. Closed due to the discovery of a ‘courting couple’ inside, the whale is now open only at Christmas where children can visit Santa there… Another fascinating, if telling, story about whales and tourist economics.

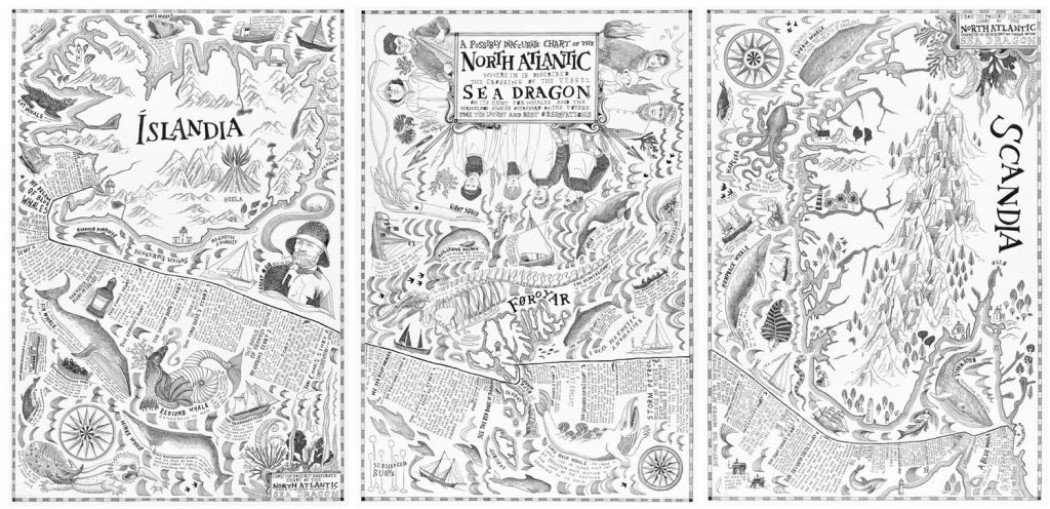

As a result of the residency, my final piece of work became a set of three interlinking maps including both drawings and text – part maritime chart, part log book. Throughout, I recount the stories I heard on the journey – from the crew, from the harbourmasters, the bartenders, the whale-watchers, the whale hunters and eaters. Some had been recorded as part of an interview. Some were overheard on board and memorised. Like all travellers’ tales, details were probably changed and the absolute truth cannot be certain.

The timelessness of being at sea hasn’t changed in centuries.

Influenced by the ancient Carta Marina, the maps also swim with drawings of the fantastic whales that Medieval people thought existed in the Northern waters. The Cat Whale with its feline cries. The Ling Back Whale with heather growing from its spine. The corpse eating Nahvalur….We had seen so few real whales on the expedition that they could have been just travellers’ tales too.

My overall experience was one of the timelessness of being at sea, that sailing across oceans – looking for whales to hunt or to study – hasn’t changed in centuries. The same stories are told of storms and drownings, of smuggling rum or drugs or guns, of ghost ships and pirates and the rocks where mermaids or skinny-dipping Swedish girls swim. Sailors are still whistling for the weather, watching the storm petrels walk on water and trusting the spirit-white gulls to lead them home. And I am still telling my own stories, six years later, of the whales and my travels on The Whale Road, that old Viking term for the sea.

Whales have clearly held a fascination for people since the beginning of time, whether for food, for tourism, as a cultural signifier or in my case, as inspiration for artwork. Only time will tell whether this value will be the saving of them or their destruction.

Adapted from several posts first published on Helen Cann’s website, helencannfineart.co.uk

This is part of ROOT MAPPING, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring which maps might help us live with a clear sense of where we are. ROOT MAPPING is conceived and edited by Melanie Viets.