Book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid, released last year in a posthumously published translation by Seamus Heaney, is concerned, amongst other things, with the inadequacies of art. In it, Virgil describes a mural painted by Daedalus, the mythological artist, which fails in its attempts to represent the death of his son, Icarus. In Heaney’s translation:

……………………………………………………………….Twice

Dedalus tried to model your fall in gold, twice

His hands, the hands of a father, failed him.

Here, art grapples unsuccessfully with grief. Daedalus’s identity as an artist is consumed by his identity as a father, and his bid to transform his loss into a tangible object is doomed to failure. It is interesting, then, that in its new limited edition print run, available in just seventy-eight copies, Heaney’s translation is itself turned into an art object, accompanied by a series of illustrations by the Dutch artist and architect Jan Hendrix. Hendrix’s images, currently on show at Shapero Modern, do not attempt to represent the mythological underworld described by Virgil in Book VI, embarking like Daedalus on a doomed effort to depict death. Instead, Hendrix confronts the reader (or viewer) with a surprising juxtaposition, contrasting Heaney’s translation, accompanied in this edition by Virgil’s original Latin, with the arid landscapes of Yagul, an archaeological site in Mexico. The result is a startling but powerful collaboration which approaches Virgil from an unexpected and original perspective.

Hendrix has spent much of his life living and working in Mexico, and its landscapes have informed his previous collaborations with Heaney. The Golden Bough (1992), a translation of a shorter excerpt from the Aeneid’s sixth book, and The Light of the Leaves (1999), a collection of poems dedicated to fellow poets, both drew upon imagery of Yagul. Hendrix himself explains his choice of subject matter to me:

“One of the reasons why Yagul was chosen as a databank of forms and sensations is that it is an archaeological site that fits very well into Heaney, my own and Virgil’s vision of mythological landscapes. Yagul is marked by leftovers of culture, a scarred landscape, reflecting the presence of nature and man in a very clear way. If Virgil had known it he would have liked it and been inspired by it.”

Despite the boldness of its claims, Hendrix’s statement gestures at a crucial element of the Aeneid, whose narrative describes the quest of Aeneas, displaced after the destruction of Troy at the climax of the Trojan War, to establish a new settlement in Italy, the original home of his ancestors. This settlement itself becomes Rome, and Virgil narrates a clear line of descent from several of his Roman contemporaries back to Aeneas. The poem’s investment in ideas of legacy fits closely with Heaney’s selection of Virgil as a literary antecedent, and with Hendrix’s choice of Yagul as an accompaniment to Book VI, whose narration of Aeneas’s descent into the underworld echoes Virgil’s wider themes of heritage and ancestry. Hendrix described to me the significance of the underworld in both his illustrations and Virgil’s text, arguing for the importance of Yagul’s ‘tombs, the presence of the underworld and afterlife as you will find in most pre-Hispanic sites or as in churches and churchyards’. Yagul connects ‘the ritual space, the burial space, the strategic space,’ reflecting the nature of a Virgilian underworld which provides a space for ritual and memorial, but also strategy and prophecy; it is in this underworld that Aeneas finds his father and is told of Rome’s future prowess as a military empire.

Hendrix’s illustrations are also in keeping with Virgil’s insistence on the inability of art to reflect the events of his poetry directly. As with Daedalus, Aeneas’s desire to materially repossess the dead is thwarted upon his encounter with his father:

Three times he tried to reach arms round that neck.

Three times the form, reached for in vain, escaped

Like a breeze between his hands, a dream on wings.

Instead of attempting the same form of material capture, Hendrix evokes death and the afterlife through his illustrations at the same time as he evades them, dwelling upon the symbolism of a ‘scarred’ memorial site as opposed to a more literal depiction of the underworld. In doing so, he also echoes Heaney’s approach to translation. Heaney viewed translation as a dynamic process – not simply a matter of retaining fidelity to the original text, but of moving it forwards in time and allowing it to accrue fresh resonances and implications. In his essay ‘Title Deeds: Translating a Classic’, he compares The Burial at Thebes, his translation of Sophocles’s Antigone, to the burial of IRA hunger striker Francis Hughes in Northern Ireland in 1981. As a result, he suggests that Antigone exemplifies dúchas, an Irish word which signifies, by the Royal Irish Academy’s definition, ‘inheritance, patrimony; native place or land; connection, affinity or attachment due to descent or long-standing; inherited instinct or natural tendency’. Through the act of translation, Sophocles’ play shifts in time and space to embody a specifically Irish sense of place and national identity, demonstrating the endurance of its ideals beyond a particular historical moment. Likewise, in this translation of the Aeneid, a Latin text commissioned by Emperor Augustus to champion the greatness of Rome, the mutability of poetry is affirmed by Hendrix’s illustrations, whose depictions of Mexico transfer Virgil’s themes of memory and legacy to a remote but kindred time and location.

Hendrix’s illustrations transfer Virgil’s themes of memory and legacy to a remote but kindred time and location.

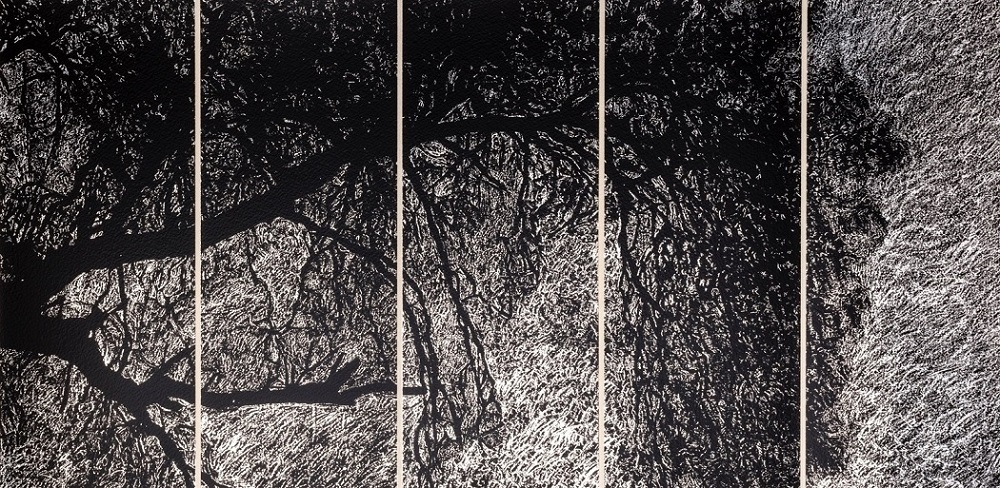

Mounted on linen, the original lithographs of these illustrations form the basis for Hendrix’s Shapero Modern exhibition, alongside a number of silkscreen prints on silver leaf. The images display a mixture of open and chaotic spaces, alternating prints of cacti set against vast, blank skies with dark, spiky messes of trees and branches. They reflect both the dark confines of Tartarus, the punitive afterlife for sinners described by Virgil, and the wide expanses of the paradisiacal Elysian Fields, where Aeneas discovers his father, Anchises.

Hendrix’s exploration of the interplay between light and dark builds upon his previous illustrations for The Golden Bough and The Light of the Leaves. Heaney’s essay ‘Ramifications: A Note on Jan Hendrix’ observes the ‘solar and Stygian’ effect of Hendrix’s illustrations for The Golden Bough, and the ‘profound recesses of lightness and darkness’ of The Light of the Leaves. Hendrix says of this latest collaboration that ‘it is very much a continuation of the imagery of the former two books. But it is also more Dantesque, darker, dreamlike.’ In citing Dante, another poet who took Virgil as an example in his depictions of the afterlife – and who influenced Heaney’s treatment of a similar theme in his poem ‘Station Island’ (1984) – Hendrix places his collaboration with Heaney in a long heritage of poetic representations of the underworld, emphasising the enduring resonances of the Aeneid across time.

Although Hendrix’s work as both an artist and architect takes place across a wide range of scales, drawing is always central to his creative process. ‘All my incursions in different media start with drawings,’ he tells me, ‘which are translated, redrawn and morphed into a suitable scale/size for the project at hand.’ This discussion of drawings ‘translated’ into different scales and media recalls Heaney’s own description of the translator’s role: that of bringing texts to bear upon a range of different cultures and identities. Here, visual art takes on the same plurality, flexible and adaptable across various cultural contexts and forms of media.

There is clearly an affinity between Hendrix’s work and Heaney’s. As Hendrix himself puts it:

“Heaney’s poetry has the power of using every day images and connecting them to the great mythologies of the world. I hope I can mirror myself in that capability. Heaney’s poetry is very visual while my work has a narrative to it and hopefully a poetic atmosphere.”

This sense of the mutual entanglements of language and image illuminates the success of Heaney and Hendrix’s work together, which draws upon the qualities of both mediums for its effect. Hendrix praises Heaney’s ‘capacity to express grand ideas through a minimum of words’ – what he describes as ’an enviable economy of means’. Hendrix’s own work displays a similar ‘economy’. Black ink prints against a metallic background provide a striking but restrained compliment to Heaney’s translation. Shapero Modern – a gallery space located beneath antiquarian bookshop and dealership Shapero Rare Books – is an ideal location for this marriage of language and images, showcasing the visual and verbal interplay of Hendrix and Heaney’s collaboration.

Despite this juxtaposition of visual art and the written word, Hendrix does not see his work with Heaney as fitting into a tradition of artists’ books. Hendrix describes artists’ books as ‘fairly recent invention’ and ‘a post-68 effort to make the artist more independent of the gallery-controlled art market, a failed but important search for utopia – a white page as a space, as a white wall.’ Instead, Hendrix thinks of his work with Heaney within a tradition of coterie publishing – a more private, labour-intensive process than mass printing, and one which is reflected by this edition’s very limited print run. ‘Our books are made more in the tradition of first editions,’ he says, ‘using techniques that go back to the great letterpress productions of the eighteenth and nineteenth century and made for friends and family’.

The cacti provide a powerful memorial not only for Hendrix’s relationship with Heaney but also for the landscapes themselves.

Heaney shared this interest in the material questions of bookmaking. In ‘Hermit Songs’, a sequence of poems in his final collection of poetry Human Chain (2010), he celebrates the writing practices of a series of Irish monastic figures from the sixth and seventh centuries A.D., describing the creation of their ‘berry-browned, enshrined’ books: ‘The cured hides. The much tried pens.’ Likewise, his translation of Virgil looks to the past not only for its classical source text, but also for a principle of bookmaking – a celebration of the book’s form as a material object. Although Virgil finds cause to criticise the art object for its failures of representation in the Aeneid, Heaney and Hendrix nevertheless celebrate the object – as both text and illustration – in and of itself.

Hendrix’s use of Yagul invokes one final preoccupation which he shares with Heaney – the representation of the natural world. Heaney’s translation draws out Virgil’s natural metaphors, such as his description of the dead souls of the underworld as:

……………………………………streaming leaves nipped off

By first frost in the autumn woods, or flocks of birds

Blown inland from the stormy ocean, when the year

Turns cold and drives them to migrate

To countries in the sun.

Similarly, Hendrix’s accompanying images are almost exclusively occupied with an unmediated natural landscape, bringing to the fore these metaphorical aspects of Virgil’s poem. However, Hendrix sees subtle differences between his approach to the natural world and that of Heaney:

“In Heaney’s work nature is like a stage design for a play, peopled with Beowulfs and fathers, while, when I put nature on the stage, nature is the play. My interest in the natural world has become an almost obsessive research in plant life, botany, analysis of landscape, cartography, topography and the greater field of natural science. Research has become as important as results.”

The importance of nature to Hendrix is clear from his illustrations – despite his earlier claim that the Yagul landscape ‘reflect[s] the presence of nature and man in a very clear way,’ traces of the human are conspicuously absent from his work, which for the most part depicts Yagul’s flora and its landscapes as opposed to its archaeological remnants. This artistic and personal investment in nature is reflected not only in the cacti and the intermeshing branches of Hendrix’s illustrations for the Aeneid, but also in his broader artistic practice. Much of Hendrix’s larger scale architecture and sculpture is made up of intricate tree and flower motifs, and this element of his work is represented by the exhibition at Shapero Modern, which, alongside his illustrations, features ‘Magic Lantern’, a small silver lantern made up of a delicate trellis of interlacing branches. This lantern, along with his architecture, reconstitutes objects made by and for humans, suggesting that they are composed of natural rather than man-made materials. As with the landscapes that are set alongside Heaney’s translation, nature crowds in upon the human in Hendrix’s art, troubling the clear lines often drawn between the two.

However, the vulnerability of nature in the face of human intervention is also made clear in Hendrix’s work. The press release for the exhibition includes a statement from Hendrix which reads: ‘as a farewell to a dear friend and a dear place, I have vowed never to return to Yagul again,’ noting that ‘strangely enough the cactuses that I portrayed in 1992 and 1999 and the years in between are now dying and disappearing.’ The themes of mortality that permeate this new edition also extend to the natural subject of its illustrations, which represent another type of loss – the steady decline of the environment. The images of cacti that line the walls of the exhibition at Shapero Modern therefore provide a powerful memorial not only for Hendrix’s relationship with Heaney but also for the landscapes themselves.

The most palpable loss represented by Heaney and Hendrix’s Aeneid, however, relates to the context in which this edition was composed. The translation is based on typescripts and initial proofs that were in Heaney’s possession prior to his untimely death in 2013, and its subject matter provides a neat but unsettling analogue to the circumstances of its publication; Heaney’s daughter Catherine, in the introduction she delivered at the Shapero Modern launch, remarked that ‘Book VI is all about the afterlife, and so it proved with this edition’. The text, Heaney’s final published work, therefore becomes a form of memorial for the poet himself, who in the act of translating Virgil was also unwittingly writing his own epitaph.

The most palpable loss, however, relates to the context in which this edition was composed.

In remembering Heaney, Hendrix praises the poet’s ability to thread together autobiographical elements with those from literature or history: ‘Seamus made permanent use of mythology as a way to tell us about simple events in his own life and made permanent use of small stories to tell us about the great mythologies.’ This uncovering of ‘small stories’ in the grand sweep of Virgil’s epic evokes Heaney’s intimate connection to Book VI of the Aeneid, which dates from his youth. In the ‘Translator’s Note’ to the Faber edition of this translation, Heaney recalls the influence of Father Michael McGlinchey, his Latin teacher at St Columb’s College in Derry, whose repeated response to the other sections of Virgil they were required to study was ‘Och, boys, I wish it were Book VI.’

Heaney revisited this personal relationship to the sixth book of Virgil’s epic in ‘Route 110’, another poem in Human Chain. The poem, which begins with an account of the autobiographical narrator’s purchase of ‘a used copy of Aeneid VI’ in a local bookshop, transposes the mythic underworld of Virgil’s text to the Northern Ireland of Heaney’s upbringing. Aeneas’s fleeting encounter with the ghost of his former lover Dido is compared to a teenage break up, ‘a sports day in Bellaghy’ becomes the ‘green meadows’ of Virgil’s Elysian Fields, and the birth of Heaney’s granddaughter, to whom the poem is dedicated, replaces the inventory of future Roman heroes with which Book VI concludes.

In the same manner as Hendrix’s illustrations of Yagul, Heaney transports the text across time and space, choosing to represent the value of Virgil’s poem not directly, but through its relation to a poignant series of touchstones in his own life. Given this personal dimension, the posthumous publication of Heaney’s translation of Book VI proves a fitting conclusion to his career, drawing directly upon one of his most influential source texts. This final collaboration between Hendrix and Heaney is not only a translation but a memorial to Heaney, commemorating his loss through its resurrection and transformation of a poem which the late poet returned to throughout his life and writing.

The Aeneid Book VI. Heaney Hendrix is at Shapero Modern, London until 18th February 2017.

All images copyright Jan Hendrix 2016, by courtesy of Shapero Modern