When you enter a gallery transformed by the artist Claire Morgan, you are immediately transported to a magical place that unsettles your basic human understandings––a floating world that defies gravity and rational thought. The body of a dead fox hovers midair surrounded by a precisely measured cube made of suspended bits of ripped plastic. A sphere of thistle seeds wraps a diaphanous force field around a falling crow that seems to be frozen in time, endlessly falling and also not falling. A plane of gold flies floats above a dead chaffinch as if carrying his spirit upward. The world she creates is beautiful––in its composition, its airyness, its patterns––and is wildly discomfiting at once. Death and life intertwined; gravity and time stop; and creatures designated as pests are presented as lovely, as an integral part of the constellation of beings. Here, you enter the deeper mystery of interconnection between the human and nonhuman worlds in this moment of global environmental devastation.

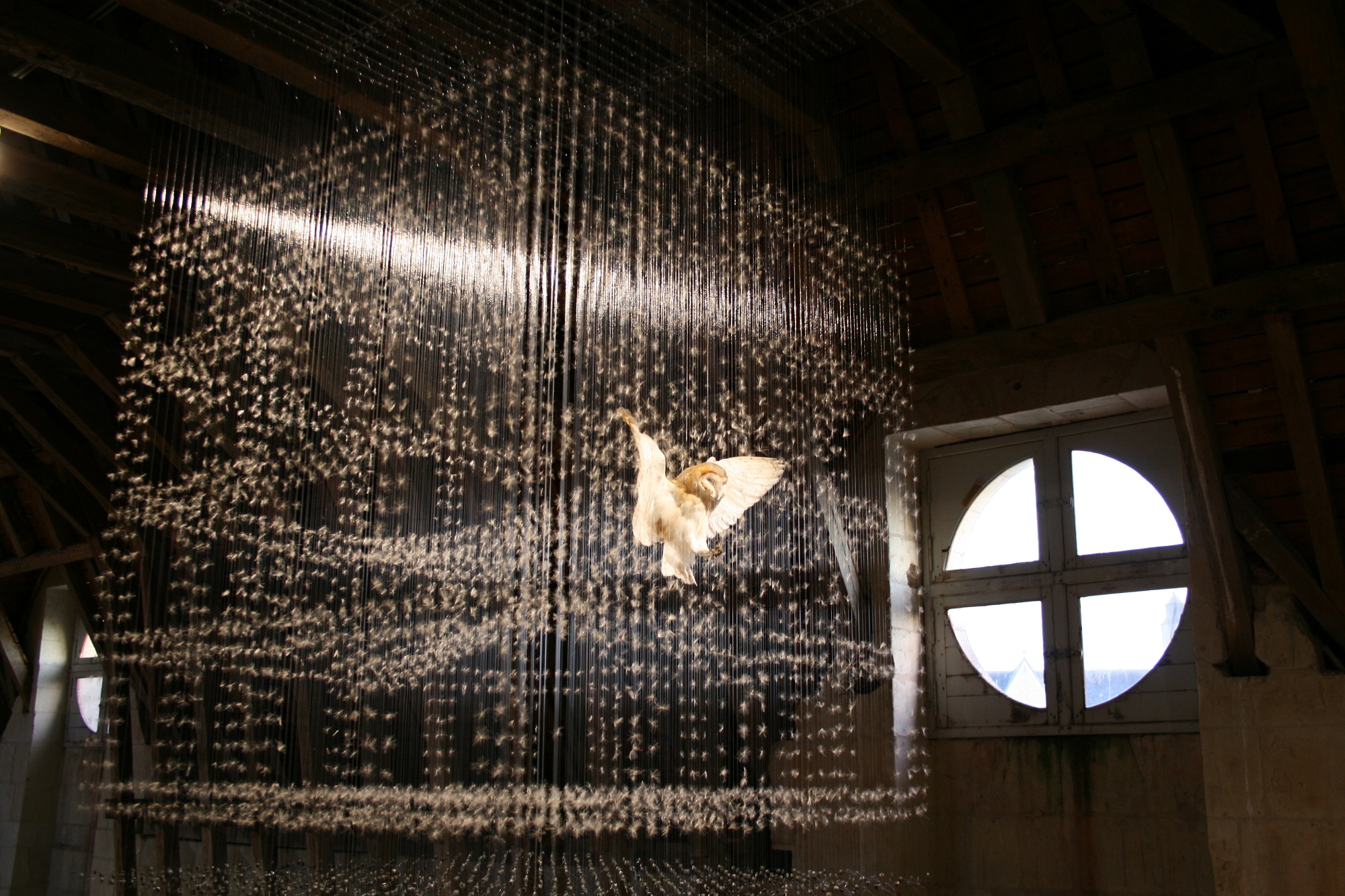

Many of Claire Morgan’s installations feature a central taxidermied animal surrounded by an atmosphere created by dead insects or flower petals or bits of plastic hung on invisible threads. In Here is the End of All Things, Morgan has created three cubes out of suspended thistle seeds and one out of bluebottle flies. A barn owl appears to have tunneled through the first three cubes and is arrested at edge of the fourth, with wings open, as if caught mid-flight, perhaps in the moment of exiting this realm. The dead owl looks strangely alive, immortal.

I am not accustomed to picking up newly-dead animals…

I am not accustomed to picking up newly-dead animals, like Claire Morgan. I do have piles of individual bird feathers and nests, shells, and even the skull of a racoon on my mantle at home, but I have not ever done the work of picking up an animal who had recently died.

On a canoe trip this summer, around the edge of a marsh, I noticed an awkward splay of long, mottled feathers lying still in a tuft of grasses on a tiny island no more than six feet wide. My friend and I moved our canoe closer to investigate. Face down with wings spread wide and head pressed to the ground, a great horned owl seemed to have fallen from the sky like a crashing plane. My chest tightened. The ungraceful end of such majesty seemed wrong somehow. There was no sign of violence. What had happened? The soft small feathers by her ears moved slightly in the night air. We could not tarry too much longer or it would be dark. I could not stop thinking about the owl. In a week’s time, I went back, and a sprinkle of tiny blue flowers had bloomed on the minuscule island. Forget-me-nots. I vowed to return for the skeleton later, once the insects and time had done their work. Unlike Claire, I had no idea how to preserve the owl, but I wanted to honor her somehow.

I knew little about the practices of dead animal preservation, but I teach on a campus that has a remarkable zoological collection. Inside one of our large stone edifices are boxes filled with mammal and reptile skeletons, shelves covered with glass jars full of dead fish and amphibians, and drawers filled with extinct birds and the hides of common rodents. “Bones and skins”, our curator once explained to me during a visit, “are useful for different kinds of research.” It’s like a library of dead bodies, nonhuman ones. A few of the skeletons are articulated: a six-foot-long sea turtle from the Galapagos, a chimpanzee, a bat. And several others have been preserved to look like they are perched or poised on pedestals: a wolf, a beaver, a great horned owl.

Many of these animals are endangered, some on the extinction list, some already gone. All of these zoological specimens died naturally. Dead animals can tell us a lot about what is killing them. Some have been shot, others sickened by diseases, others poisoned. They can also tell us about environmental change over time. At the Field Museum in Chicago, the amount of soot found in bird feathers told a story about air pollution over the Rust Belt in the early 1900s. There are so many stories.

In the “skins” preservation room, I watched a woman turn a warbler inside out, slicing the belly first, emptying the body, peeling the skin back carefully so as not to damage the feathers, and then preparing it to be stuffed with cotton. The “bones” preparation involved a flesh eating beetle colony. The curator and I walked down a musty cement tunnel into a chamber with several large tubs. The beetles would not eat live flesh, she assured me, so we were not in any danger.

The label ‘pest’ gives us permission to kill creatures without any sense of guilt.

When I found the owl, I knew I could not do any of that, so I thought I would let nature do its work, the insects and the fungi so efficient at helping things decompose and return to soil. I assumed the bones would remain, and I could take the skeleton then.

The great horned owl was not a common sighting to us. Lately, I have been watching the juvenile barred owls in the woods near my home. Their already huge wings are nearly silent as they drop to the ground to hunt. Several times, locked in the gaze of their large piercing eyes––eyes that could spot prey scores of feet from the ground––I felt relieved I wasn’t a rabbit, a shrew, or a mouse. Barred owls and great horned owls eat many of the same things, but the great horned owl is the larger apex predator. A young barred owl could be attacked by a great horned owl, but the great horned owl has few enemies here. We described the death scene to a falconer we knew and she said the death was most likely due to pesticide poisoning.

The National Institute of Health defines pesticides as “chemical substances used to prevent, destroy, repel or mitigate any pest ranging from insects (i.e., insecticides), rodents (i.e., rodenticides) and weeds (herbicides) to microorganisms (i.e., algicides, fungicides or bactericides)”. It goes on to say that over one billion pounds of pesticides are used in the United State each year and approximately 5.6 billion pounds worldwide.

Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary defines a pest this way: “a plant or animal detrimental to humans or human concerns (such as agriculture or livestock production).”

To Claire Morgan, this very definition is problematic. She told me, “Whenever I am making my work, I am using bodies of animals, and quite often these are animals that humans regard as pests….We are animals, we are part of the natural world. We tend to behave as if we live ON the natural world, like we are separate entities that can use it, take advantage of it, that it is our resource, when really the earth is one huge organism that we are part of.”

The label “pest” gives us permission to kill creatures within the same system we are a part of without any sense of guilt. Our stories and myths have demonized so many creatures: spiders, bats, mice, crows, wasps, snakes, even dandelions. In our attempts to eliminate these beings for our convenience and comfort, we not only break strands of a fragile web, we destroy countless other beings in the process. Bees, frogs, songbirds, owls…even humans can be damaged by this killing practice. The Audubon Society reports on the horrific deaths of owls who have died from internal hemorrhaging after eating rodenticides. Many others are sickening slowly.

Claire Morgan’s work tells us a new story. Her pieces honor all of the animals in them. Pests are just creatures that are mortal like we are. They are part of our interconnected world. They are kin and we have created this imbalance.

The baby barred owls will be hunting further from their home soon, over yards covered in pesticides.

In one installation, called Elephant in the Room, a nebula of tiny pieces of torn paper (that she sees as a symbol of our obsession with reckless consumption) creates the shape of a fourteen-meter long North Atlantic right whale. The enormity of the sculpture is balanced by the immaterial ethereal aspect of the giant mammal as it swims above you through the air. Ideas of impermanence and the danger of a looming extinction come into my head, but the piece also offers another more haunting sensation as if this might be a sacred moment caught by an artist, the whale spirit living on. A ghost whale perhaps with a warning.

The poet and artist Ian Boyden once told me a story about traveling to Mitla, an archeological site in the state of Oaxaca in Mexico. As he walked along the edge of one of the elaborately carved stone buildings, he was suddenly surrounded by thousands of white moths fluttering madly around him. For a moment he was blinded and also completely dazzled by the frenzy of wings. Moments later they disappeared, and Ian noticed that a guard who stood nearby had seen what happened was laughing heartily. “You looked like a cloud,” the guard said. “The clouds are the intermediaries of the gods. Looks like they were trying to take you!” Reflecting back, Ian said at that time he was “too heavy”. He had “no spiritual helium”. They had to put him back down.

The whale in Claire Morgan’s work seems to be light enough. I think of all the animals facing extinction and how none of them have caused this crisis. I carry the weight of that.

The baby barred owls will be hunting further from their home soon, over yards covered in pesticides. The other night I sat on the ground in the dark under a tree where one had perched. I watched her swoop from branch to branch, her elegant brown and white wings riding the breeze. Then she would pause to peer at the ground intently, often looking directly at me, perplexed perhaps by my rapt attention. And then suddenly, she dropped down to the ground just a few feet from me, staring straight into my eyes. I held my breath, heart beating wildly at this gift. And then just as suddenly she took to the air again, the wind from her wings whooshing over my face. How, then, could I do anything but tell her story, the story of her radical trust, her faith that this human would do her no harm?

Image credits (from top):

Claire Morgan, Here Is The End of All Things [detail], 2011. Photo: Claire Morgan

Claire Morgan, The Blues (II), 2009. Photo: Claire Morgan

Claire Morgan, Gone to Seed, 2012. Photo: Jordan Hutchings

claire-morgan.co.uk

This is part of ROT, a section of The Learned Pig exploring multispecies creativity through modest tales of collaboration and coexistence amidst world-ending violence and disorder. ROT is conceived and edited by Julia Cavicchi.