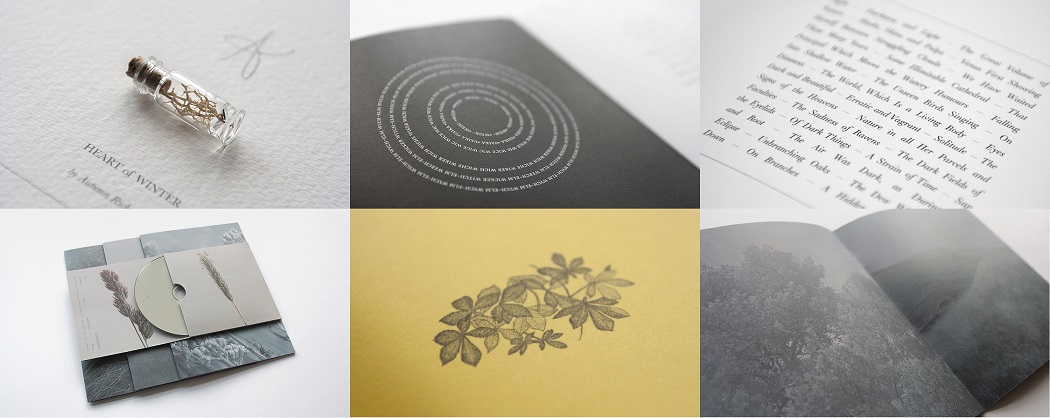

Run by Autumn Richardson and Richard Skelton, Corbel Stone Press is one of the most distinctive small presses around today, whose work spans books and journals, pamphlets, booklets and music. Their focus is on landscape, nature, and ideas of place – mostly through poetry, but also across painting and drawing, botanical illustration, sound and song. Everything they do is painstakingly produced, subtle, and beautiful, with a poet’s love of language and an artist’s dedication to aesthetics and materiality. Every new release from Corbel Stone Press is an object to be cherished.

In the past, we’ve reviewed Corbel Stone Press publications such as Tasked to Hear by Mark Peter Wright and the Reliquiae journals. We’ve also profiled artist Rebecca Clark, who has collaborated with Corbel Stone Press too. This time, as part of our ongoing Wolf Crossing editorial season, we spoke to Autumn and Richard about the importance of translation in both their poetry and their publishing.

Although etymology, forgotten words, and arcane terminology have been long-standing facets of your work, the Reliquiae journals contain (what seems to me to be) a growing emphasis upon works in translation. Could you say a bit about why this has become important to you?

Translation has been fundamental to Reliquiae from the beginning, but commissioning new translations is time-consuming and expensive – seeking permissions, finding a translator and then working with them – so the apparent growth of translations in the journal may simply reflect the culmination of work which has taken several years to come to fruition. Having said that, we are keen to feature more translated work in future. One simple reason for this is that – as English speakers – we realise that the English language itself is informed by many languages, and that the English-speaking cultures assimilate a diverse range of influences. Moreover, as our editorship is Anglo-Canadian, we are not simply limited in our focus to the British Isles. In future we would like to include a greater diversity of languages than we have been able to feature hitherto – which has necessarily reflected the limitations of our resources and contacts, rather than our ambitions. Put simply, we are interested in worldwide perspectives on the natural world, albeit refracted through a literary lens.

Given that (I’m assuming) most of your readers are English language speakers, why do you publish most translations in both the original language and in English?

It’s vitally important to include, wherever possible, the original language text alongside the translation. This is partially a matter of simply acknowledging and respecting the source material – it’s an issue of parity and equality. But it also gives the reader the opportunity to experience the music and rhythm of a different language; to observe connections and differences between languages, to find equivalences and to learn new words. Even if we may not know the language, exposure to it through simply sounding the words is surely a beneficial experience.

Even so, many words remain untranslated through your works – scientific terminology, ancient names etc. How powerful (or otherwise) is the ultimate untranslatability of certain words? Especially proper names of people and places?

The place-names that are powerful to us are those which offer a window into the ecological history of a landscape. These names are necessarily reducible to their constituent elements; hence Birker Fell in Cumbria is birki erg fjall, ‘mountain of the shieling by the birch trees’. But yes, there are other names, such as Devoke Water, whose etymology is uncertain. And, of course, enigmas have a powerful effect upon the imagination.

But if you trace words back far enough, they all pass beyond the threshold of certainty – beyond their ‘attested’ written forms into a spoken – and therefore lost – past. This is true even of the most transparent, ‘ordinary’ words, so perhaps what is needed is an acknowledgement of the miracle of language itself, rather than making special cases for individual words. Much of our work is about giving attention to the seemingly small and overlooked – a field of grasses, say, rather than the orchid growing in it.

Many of the texts you’ve published are from antiquated, endangered or marginalised languages (Old Norse, Gaelic, Inuit). Is that a deliberate focus? If so, why?

Our interest is in languages that communicate powerfully about the natural world – languages that speak of an attention to, and respect for, nature. In many cases, these languages or dialects also happen to be either marginalised or antiquated, and so it is difficult not to come to the conclusion that our modern societies are becoming increasingly alienated from the natural world. Of course, there has been great historical exploitation of the environment, its flora and fauna, so we are not deluding ourselves with the simplistic assertion that ‘things were better in the past’. Nevertheless, we have made it our aim to salvage and celebrate what we can, whatever its origin, past or present, in order to rebuild a meaningful linguistic connection with the natural world.

With specific reference to Autumn’s translation of the poetry of Knud Rasmusson, do you see the translator’s role as a bringing to life of “someone else’s worn / little song”? To what extent should the translator sing it as their own?

The quote you mention is an English translation of a Danish translation of a Greenlandic Inuit song. What is perhaps most poignant about the ‘song’ is that its melody is lost, and only the words remain in a ghost-echo of their original form:

I sing a little song,

someone else’s worn,

little song,

but I sing it as my own;

my own dear, little song.

And so I play

this worn out,

little song

and I renew it.

Nevertheless, despite the amount of textual distance, the words themselves are incredibly eloquent – so much so that we chose them for the cover of our inaugural issue of Reliquiae, as they seemed to say what we wanted to say. And so it is important to acknowledge how much we all individually and collectively, consciously and unconsciously, rely upon the words of others; how we circulate and keep alive what we find meaningful and expressive. Reliquiae is partly a way for us to do that; to celebrate our shared linguistic heritage and to renew it.

But your question is a good one, because it doesn’t only apply to translation. The ethical difficulties are perhaps clearer in translated work – issues of faithfulness to the original text – but these sensitivities also apply to our editorship. When republishing small excerpts from the linguistic corpora of different cultures, there are, for example, issues of appropriation and misrepresentation. A great deal of tact and sensitivity is required when crossing into different cultural territory and we only hope that our highlighting of other cultures is seen as respectful and celebratory.

Do you see the process of translation as something from which wider ethical analogies ought to be made? For example, in terms of human-animal relations…?

You raise an interesting point, and – as the focus of our work is the natural world and the other-than-human – these ethical issues are at the heart of everything we do. Respectfulness for the other – whether it’s a literary text, another human being, an animal or plant, should be a fundamental principle. In our research of ethnographic literature, we are often presented with the concept of the ‘personhood’ of other-than-human-beings – something which is antithetical to our contemporary, anthropocentric, rational-materialist world-view.

Nevertheless, advancements in scientific research seem to be eroding the very boundaries and divisions that it helped to establish. We’re thinking of, for example, the fascinating research into plant intelligence and communication; or the 2012 Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness – which, in its cautiously scientific manner, asserts that ‘humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness’. It is therefore interesting to think that the ideas of cutting-edge science are becoming more convergent with those aboriginal peoples, at least with regard to the intrinsic value of the natural world. As if to prove the point, recently, in 2017, after 140 years of campaigning, the Māori of New Zealand won recognition for Whanganui river, which must now be legally treated as a living entity. We can only hope that similar advancements are made across the globe, if we are to protect and conserve the natural world effectively.

Part of The Learned Pig’s Wolf Crossing editorial season, spring/summer 2017.