Jon and I had initially bonded over growing the bacteria SCOBY to make Kombucha, which is a fizzy health beverage. He had giant basins of the stuff. The SCOBY grew and fermented the drink in large glass basins, kept in dark cabinets with tight cloths pulled over. I used every container in my house to grow the bacteria and ferment kombucha. I kept them under a rocking chair in my bedroom. The steaming intense summer was measured by our bodies’ proximity and glasses of the drink. The brew would bubble as I was asleep and it made me feel comfortable.

SCOBY is beige and plump, wet and juicy. It is formed by the bacterial yeast in the brew, which eats sugars in the tea and makes more bacterial yeast, producing carbon dioxide. The bacteria grows like skin on the top of milk. Once a layer of SCOBY is formed and is thick enough, the ‘mother’ sinks, and a new (semi-separate) layer develops on top. The bacteria seems to be capable of growing endlessly thick, taking the shape of whatever container you put it in.

Though I didn’t know it immediately, I was drawn to SCOBY because it is incredibly difficult to categorise as either alive or not. This stands in opposition to the steadfast cultural juxtaposition between life; facilitated by the West’s obsession with hyper-sanitisation. Non-human life is under complete control when shown or interacted with – like in scientific experiments or the domestication of plants and animals.

To articulate this, I wanted to create an installation that pictures life between states. Repulsive and curious things housed in controlled, pseudo-scientific/white cube ways. The barrier between self and repulsive foreign life object had to be slim enough to challenge the distance between the two. I ended up creating an installation which held rotting plants, rotting chicken and a growing SCOBY in slim acrylic boxes.

I first grew the SCOBY for the installation in my parents’ bathtub. After it had grown, I peeled the skin off the liquid and held it up to the light. The bacteria measured 40cm by 13cm, mirroring the size of the tank it grew in. I was flabbergasted by the bacteria’s visceral, skin like quality and the way it grew on such a large scale. Then, out of nowhere, clear awe flipped to clear disgust. I was instantly repulsed by both the bacteria and myself for growing it. My mom came into the bathroom and had the exact same reaction, she was initially drawn in physically, but then flinched right back to the other side of the bathroom.

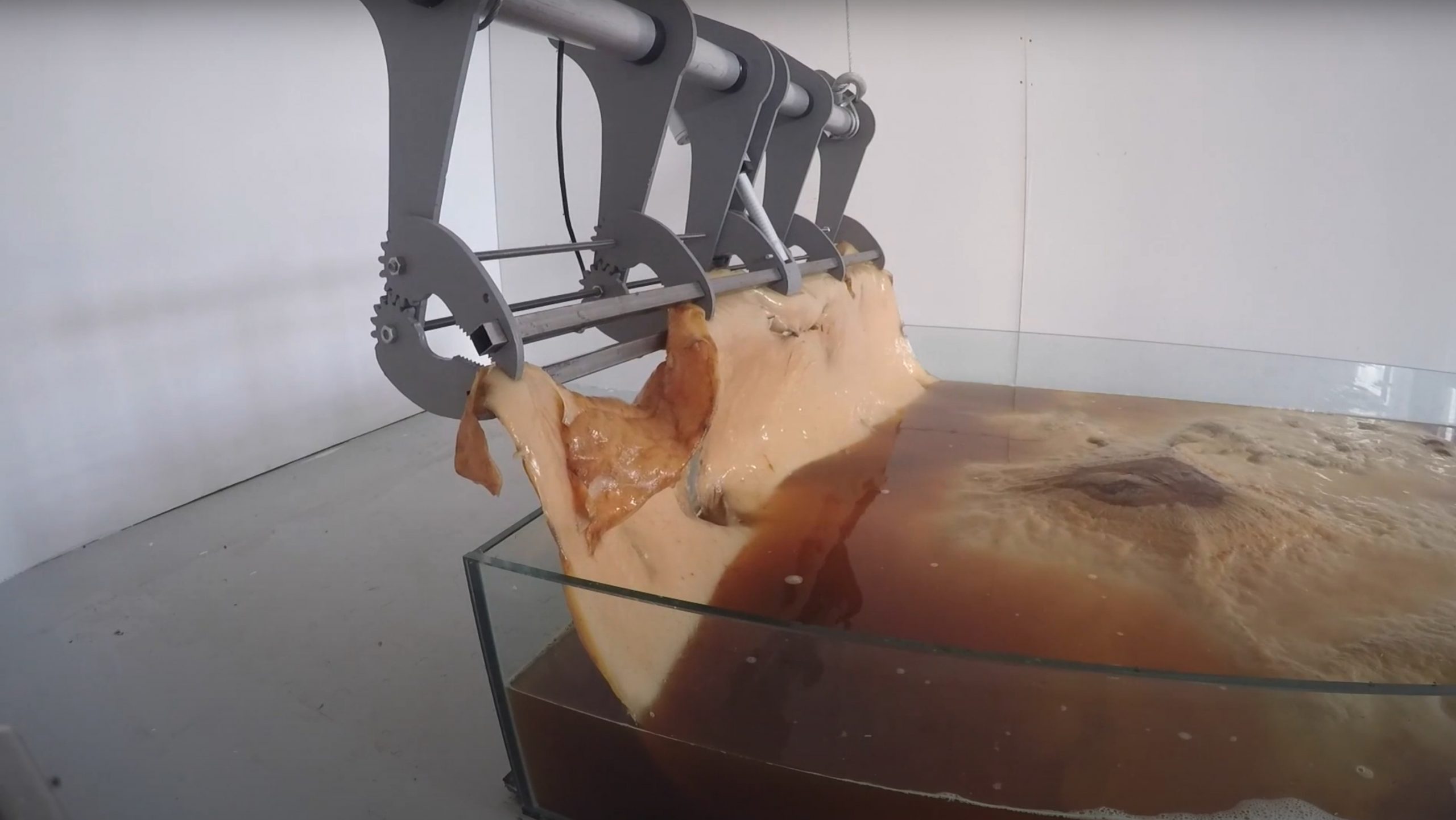

I moved to England shortly after to do a master’s degree at Goldsmiths. I wanted to capture the reaction my mother and I had to the SCOBY. I decided to grow a SCOBY on a very large scale in a tank that I designed for a specific corner of my art school. The corner was beyond some doors and between studios. The tank was six foot by four. I decided to design a machine that would come down from the ceiling and pick the bacteria out of its vat in order to be looked at. The action would replicate what happened in the bathtub, but allow some distancing from the bacteria. The distance would not be enough, and could probably never be enough, because of the size of the bacteria and the alienness of the overall action.

The machine took around a year to develop. I met a collaborator who ended up building a majority of it at a DIY Hackspace in London. Thank God for Patrick Dent. Patrick makes robots in his free time when he’s not playing in rock bands or delivering pizza. He was up for the challenge and started to build the machine. It was not an easy build. One of the larger issues ended up being that the clawed machine had to grab the organic material and lift it up out of its vat strongly enough so that it would hold but gently enough to prevent it from breaking.

While we were figuring out how to build the machine, the SCOBY grew to be enormous. People within my studio started to complain about it. Some were terrified for their safety, claiming it would affect the air quality. I wrote multiple health and safety reports about how the bacteria was unharmful. It is made from yeast already present in the air. The studio manager nonetheless made me install a ventilation system (much like one would install in a bathroom) that channeled air from the bacteria outside. I got help installing a fan and ran ducting to the brew.

Complaints kept on coming in even after the ventilation system was installed. I had to add five metres of ducting outside of the window to lead away from the studios. More complaints necessitated running the ducting over a fence into an adjacent creek. A health and safety manager on site eventually told me that I was polluting the creek, and I would get in trouble with the council if I did not bring the ducting back towards the studios.

What was hilarious about this was that the creek was already comically polluted: filled with shopping carts, fabrics, plastics, metals, tires and boats which looked like they had been there for decades. I ended up having to add eight metres to the ducting, running it back alongside the building, out of the creek and past everyone’s studios. Although I was definitely complaining (silently to myself) when adding and adjusting the ventilation system so often, I think they proved to be rich additions. The installation became a portrait of people’s paranoia and hatred of the bacteria in conversation with the architectural qualities and geographic location of the studios.

I think it is important to say that SCOBY has been growing internationally in homes for thousands of years. So it is safe, relatively. Like any food product, it could become dangerous if it grows mould. In Northern China it has been known as immortality tea, and people would pass the mother through generations. The bacteria is also similar to what is used to ferment vinegar. But this is besides the point: SCOBY’s alien presence becomes heavy in people’s minds. One person said that the smell was so repugnant because you can tell it is organic and that solvents would be better. Solvents of course are toxic, but even though they smell (I would say just as much as the brew), the toxicity is more mundane to many people. The smell is related to a secure knowledge that it belongs to human construction: it is sanitised, finessed, made for human purpose – deep breath in, deep breath out.

But, alright, it makes sense why people are terrified of SCOBY. It is incredibly alien, and it is also a beast. Because the machine took so long to develop, the bacteria became huge. After seven months, I needed a team of six to move it out of its vat. This particular SCOBY was made with 300 litres of tea and 27 kilograms of sugar. The team did a performance in which they (collectively) figured out how to move the thing and bring it to a scale in order to be weighed. It ended up weighing 110 kilos. They used ratchet straps and slides to get it out of the tank. When it was on the scale, everyone was debating how they should stand next to it for documentation. The photo looks like a group of engineers standing next to some new fast car.

Patrick eventually figured out how to make the machine with a drill he used for the motor. The one thing he wanted me to mention in this article is that he used the program Fusion 360 to test the design of mechanics, in case it would help readers with an upcoming project. He laser-printed most of the parts. Patrick even created an app to control the bot through Bluetooth on your phone, monitored by a blinking heart beat. He came in late nights after pizza delivery shifts to help me try the lift. The robot would pick the bacteria out of its vat, and it would work for about five minutes, and then the bacteria would slip out of the claw of the machine and splash back to where it came from. He would drive me home afterwards and we would listen to his band’s new rock music as we discussed new developments happening in our lives.

I grew the bacteria about eight times. Each growth was around two months. The robot breaks the fragility of the skin on top of the liquid, so any articulation of the installation requires new growth. Patrick and I figured out that we needed to grow the bacteria with some space from the tank so the claw could get under it (I loved the bubbles the bot made as it eventually submerged into the dark tea). I put barriers in the tank to control the growth, at first using wood and brick. The bacteria grew black. We became closer to figuring things out in final trials. I had an upcoming show at the Barbican Arts Group Trust where I was going to show the work.

Between the exhibition and moving out of my art school’s studios, I put a final version of the SCOBY in a storage unit. When signing on to the storage unit, I signed off on not holding anything liquid, alive or perishable. I smuggled the giant bacteria into the storage unit wrapped up in a blanket: removing all liquid from the tank and built a wooden structure to hold it in place. The unit was terrifyingly close to the security office. I silently dumped 30 litres of black tea into the vat. The figurative alarms in my head were joined by numerous actual alarms for a reason I don’t know. Automatic lights were flashing on and off. I spent too many anxious hours of my life in that storage unit, using a headlamp to light my way and keep the bacteria healthy and afloat.

I often have nightmares about SCOBY, and the brew. Once I dreamt that I had an exhibition where I filled large rooms with the fermenting tea and SCOBY. After opening one of the rooms, the brew flooded the entire building, and people were wading through the liquid. I was so stressed in my dream, desperately trying to flirt with the site’s management enough so they would let me go scot-free.

I’ve had bacteria under my nails and brew (unfortunately) down my pants. My practice in the last couple of years has seen me grow SCOBY more than seven hundred times. I know its always different versions of the same being, which I see in moving the liquid, always using old to create new.

SCOBY is relentless. It’s steadfast, peaceful and forceful. In disguised stillness it slowly rises. I have a certain attachment to the bacteria and feel about it almost like I used to feel about the mountains where I grew up. Large and tranquil monsters who surround and hug you in their presence. Although I do sometimes wonder if the bacteria hates me, or if it wonders why I grow it, I deeply believe it does not have feelings – and I don’t name it. But I somehow know that it’s there, and it’s alive and we have a silent and steadfast relationship.

Bianca Hlywa has solo shows based on the research covered in this article at LOA gallery, London (December 2020) and Verticale Arts Centre, Quebec (April-August, 2021).

www.biancahlywa.com

This is part of ROT, a section of The Learned Pig exploring multispecies creativity through modest tales of collaboration and coexistence amidst world-ending violence and disorder. ROT is conceived and edited by Julia Cavicchi.