By the time I was seven I had moved house four times in three countries on two continents. A few years later, I found myself dropped into another new place: a summer spent in Čelákovice, a small town in the Czech Republic. Culture shock, the hollowness of first-time jetlag, feeling so fragile and porous that the sunlight must be shining right through me. Linoleum, stark white rooms. They made me get some kind of vaccination before I could drink the tap water. There was a propaganda radio embedded in the wall that only turned down, not off, so it could flare up at any moment, those sharp, Slavic consonants marching uninvited into the bedroom I shared with my sister.

It was during this trip that I first remember reading for comfort, reading to escape my homesickness. My mom gave me a copy of Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals and I’d spend sleepless nights in our tiny, orange- and brown-furnished room immersed in that book. Durrell was an English naturalist born in India, and the book is his hilarious and beautiful account of his eccentric family life growing up in Corfu, Greece before they were forced to leave at the outset of World War II. The book and its sequels are saturated with a sense of place. For me, that summer was spent as much in Corfu as in Czech. “The warm air, the wine and the melancholy beauty of the night filled me with a delicious sadness. Lulled by the throbbing heart of the boat’s engine, lulled by the warm night and the singing, I fell asleep while the boat carried us back across the warm, smooth waters to our island and the brilliant days that were not to be” (Gerald Durrell).

This book furnished me with my first model for what it is to love a place, to incorporate it, rock, tree, and graffiti, into your life. Durrell’s writing accompanied me through that Czech summer, like an anthem to one of my earliest love affairs with a place. As Herman Melville puts it, “I have swum through oceans and sailed through libraries”. But brilliant days always end too soon. After we left, I spent months haunted by the homey dreariness of our Soviet-era apartment building, the mildew smell of the orange river that sludged through nearby locks, and the snap and panic as a branch of my regular climbing tree broke and the wind was knocked out of my lungs. I was ten and completely overwhelmed by the strength of my unasked–for attachment to this place. And unable to handle how easily it was all ripped from under me when we boarded a plane back to the US.

Feeling My Way Home

I spent a long time thinking I didn’t have a hometown. No “citizen of the world” bullshit for me, because what does that mean, anyway? Mine was a feeling of belonging nowhere, not everywhere. But in college I stumbled on a set of books that solidified what I’d always known: that I do have a hometown, or a home-place, in Nova Scotia, Canada.

This revelation came out of the niche world of Anglo-Irish big house literature: novels that narrate the decline of the Protestant aristocracy during the Troubles, often ending in the burning or bombing of their country estates. I wish that when I’d read these books as an undergraduate, my professors had given greater voice to topics of imperialism, cultural genocide, and the fact that we mainly read writing from the colonizer’s perspective. But, then again, American schools rarely find their way to facing such topics with depth or nuance. This was the same public university that midway through my second year began requiring all of us non-citizens to line up and show our papers, a bureaucratic cattle-call to rout out undocumented students.

Mine was a feeling of belonging nowhere, not everywhere.

Armed with an underdeveloped critical lens and the protective shield of my green card, I read these novels with an eye for a sense of place. The in-between-ness of the Anglo-Irish, neither Irish nor English but precariously settled on Irish land, seems to have given them a heightened awareness of place, of their particular corners of the world. Author Elizabeth Bowen manages to endow everything with a sense of form and solidity. In her world even the night has a “sticky stifling texture like cobwebs muffling the senses”. The big house itself is brimming over with a sense of location, of placeness, as it “huddles its trees close in fright and amazement at the wide light lovely unloving country, the unwilling bosom whereon it was set”.

Bowen draws our attention to places in their most physical sense, which I see as distinct from the idea of a spaces as socio-political entities. You can never really separate places from ideas—there’s no such thing as pure geography. The big house dwellers try desperately to hold on to their homes and ignore the political situation around them, but it always comes crashing down in the end. “For in February, before the leaves had visibly budded, the death – the execution, rather – of the houses occurred” (Elizabeth Bowen).

The in-betweenness of the Anglo-Irish and the sense of loss ever-present in these novels got tied up in my mind with Nova Scotia, a place where I’m neither local nor foreign. Nova Scotia is where my family comes from, but I’ve never even lived there, I’ve only visited. For a week or three months. Once a year or a few times a year. I was always leaving. Yet Bowen gave me a different way of knowing home. The solid, structural topography of her prose drew my mind to the primacy of my physical connection to Nova Scotia, to the sensory intensity of being there. The thud and splash of the oars as I row my heavy wooden dory through an island-studded bay. Feeling the sea through my sore shoulders, callused palms, and salty skin. If life hasn’t given you an obvious home, it’s ok – perhaps necessary – to just fucking pick one. These novels confirmed that some essential seed of myself, the geographical centre of this map, lies on that coast. It’s an imperfect paradise, rough around its tide-battered edges, more fog than sun. But it remains an Eden to me, and it makes a difference in your world to have a home, an anchor for your mind.

A Desert Without Scale

Back to this desert place of mine. You fly in low over those inferior foothills, the southern roots of the Rockies, over a dirt sea, dusky mountain folds casting long silhouettes in the evening – the crinkled paper discarded by the frustrated writer of geography. Phoenix lies ahead like a scab in the desert, a city built of single-story buildings, growing out instead of up, kept alive by pulsing cement arteries, its massive freeways. You can drive for hours at highway speeds and still remain within the city, it spreads so. Insistent on making its mark. Visitors say how brown it is, how very brown, despite these water-hogging golf courses, these professionally palm-treed avenues. It is dusty brown, and vast.

I spent many of my school years, on and off, in Phoenix, Arizona, but it never felt like home. It was a problem of scale. When I arrived at age seven, my world extended too far beyond the immediate routine of school, playground, and family. I was the white kid born in Asia (“Singapore, that’s in China right?”) who had left my best friends behind in places my new classmates had never heard of, whose parents dressed me in a cheongsam for the school trip to the symphony, who looked and sounded like everyone else but was somehow foreign to the other suburban seven-year-olds. Our interests and experiences had little relevance to each other.

There’s no such thing as pure geography.

Age didn’t help dissolve this communication barrier. My family kept traveling, kept moving, and the scale kept getting bigger. I’m incredibly fortunate to have seen so much of the world, but this whiplash mobility was lonely. I rarely stayed in one place long enough to become part of a community. Part-way through high school, my family moved back to my birthplace, to a verdant university campus on the edge of the city, in heartland Singapore, far from the glitzy downtown. I went to an international school, full of expatriates and immigrants, and for the first time I finally found a community of other rootless people like me.

I later discovered that sociologists David Pollock and Ruth Van Reken had given us a name: Third Culture Kids (TCKs), which refers to people who have spent a significant part of their childhood outside their passport country or outside of the cultures their parents came from, often moving multiple times. Some people think of themselves as both immigrants and TCKs, while others settle on one term or the other, or different words altogether. I felt a deep sense of relief to finally add the word “TCK” to my understanding of myself, because it emphasizes serial mobility, the experience of moving often and having to adjust to several cultures while growing up.

When my family moved back to Phoenix, this new TCK identity had to be tested against the reality of my huge, homogenous American high school, where there was no one else like me, and at first my new identity didn’t stand up very well. As a kid in Phoenix my friendships had been built while riding bikes in the desert and begging our parents to drop us off at the mall. Arriving in Singapore at 14, I discovered that teenage social life was conducted in bars and shady nightclubs that were happy to admit underage expats who had money to burn on cheap mix drinks. In that big, safe city with ample public transportation, I had to learn overnight how to navigate a completely difference social terrain.

Not long later, I lost those friends when my family boomeranged right back into the stifling insularity of suburban Arizona. I was again the outsider to the kids who’d known each other since elementary school, where conservative Christian values held sway, and if you couldn’t drive you couldn’t go anywhere. I’d spent so long chameleoning into different selves at a moment’s notice, that I had no idea how to get all these fragments of self to cohere. I was overwhelmed, isolated, and feeling more foreign than ever – not American, Singaporean, or Canadian enough – drowning in reverse culture shock, although I didn’t know that term at the time.

But, after a while, I began to rein in some of the distances in my life, to collect pieces of myself back from the places that had claimed them, and give those pieces some sort of representation. In Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, I found the first words of a vocabulary with which to understand and voice all of this. Ondaatje voiced so many sentiments that had previously been beyond my ability to say. Where I’d been overpowered by the spaces and distances in life, he caught hold of these abstractions: “Kip and I are both international bastards – born in one place and choosing to live elsewhere. Fighting to get back to or get away from our homelands all our lives”. Most of the time I don’t know whether I’m fighting to get back to somewhere I’ve loved or onward to somewhere new, but in Ondaatje I found a comrade in this bastardy, this constant fighting-to-be-elsewhere.

It makes a difference in your world to have a home, an anchor for your mind.

More important than the sense of shared history and experience, this book marked an entrance into the world of metaphor and representation. This passage was the doorway: “Within two weeks even the idea of a city never entered his mind. It was as if he had walked under the millimetre of haze just above the inked fibres of a map, that pure zone between land and chart, between distances and legend, between nature and storyteller” (Michael Ondaatje).

The world of metaphor is the millimetre of haze between thoughts and words, between the intangible and the tangible. Entering this world, I found that thoughts and abstractions can be explored, used, tempered into words, shaped to say what you need them to say. Even more than Bowen, Ondaatje’s writing is saturated with a sense of physicality: a mountain in the Sahara curved like a woman’s back, a plateau the shape of an ear. “I wish for all of this to be marked on my body”, he writes, “I believe in such cartography – to be marked by nature, not just to label ourselves on a map like the names of rich men and women on buildings”.

It was Ondaatje’s precision in portraying the abstract without slipping from the solid that triggered a desire to locate myself and learn to move within this hazy zone of metaphorical representation. At one point, somewhere after The English Patient, books and poetry ceased to be only complements to experience. Writing, whether mine or others’, became bound up with life. “Can you say how far far is?” poet Charles Olson asks. It was a long process, collecting the vocabulary and the frames of reference that allowed me to say such things. With literature as a catalyst, I started distilling all the spaces and places that cluttered my life into some sort of identity. It got easier to tolerate the dislocation that came with not being Canadian or American or anything enough when I could put words to the path I’d travelled. Bowen helped me realize that I had a home. Ondaatje helped me learn to say just how complicated my relationship to home is.

Oddities in Space

Looking back, I realize that I was also drawn to the solidity of Bowen’s prose and the sensuousness of Ondaatje’s language because my connection to my physical self has often been tenuous. The distances between the people and places in which I’d invested myself piled up like overweight baggage charges. I’d tried to pack too much of the world into myself, and it left me with a hollow, bloated feeling of not fitting. Unsure where I fit in the world, unsure how to fit this surfeit of thoughts and feelings into my skin without overloading my senses altogether.

It wasn’t until I found words and context to make sense of my TCK identity that I had space to attend to other aspects of experience. Space to realize that other things closer to home – trusted people who had violated my boundaries, family discord, the insidious daily grind of being sexualized by men – had further strained my connection to my body. I was finally able to see myself as more than just a shambling collection of passport stamps and new schools, held together by constant code switching. I also had a body, a shape, a gender, and the latter seemed as troublingly undefined as my cultural identity had been.

In science fiction I found a universe of gender creativity, from Ursula K. Le Guin’s ambisexuals to the genderless society in Ann Leckie’s space operas. Singaporean author JY Yang paints a vivid world where nagas and mages are real and people are born without gender, left free to confirm themselves as male or female when they’re ready, while other characters are nonbinary. In Yang’s stories, this gender construction is an essential piece of worldbuilding, but it’s not always active in shaping the plot; it’s just how things are. Other writers deliver plot purpose-built to scrutinize gender, like Charles Stross’s Glasshouse, which follows a set of 27th-century post-humans who’ve transcended physical bodies and yet still find themselves reckoning with humanity’s binary, patriarchal past.

I’ve done this before, wrung an identity from all the nots.

Sometime in the last several years, I can’t pinpoint an exact moment, I stepped over another border, over the confining fencepost at the edge of Woman and out into the liberating expanse of Nonbinary. This migration across gender lines has brought with it a familiar in-betweenness: not queer or straight or cis or trans enough. I try to remind myself that I’ve done this before, wrung an identity from all the nots. But it’s daunting to feel that I’m embarking on another similarly undefined journey.

I find any fiction that grapples with gender thrilling. Above all, seeing nonbinary identities depicted in literature sets off a deep gong of recognition that echoes in parts of myself I’ve only just begun to map. When Yoon Ha Lee includes nonbinary “alts” as a simple fact of life, equal to and no more remarkable than the men and women who people the warships and space stations of his Machineries of Empire, I feel deliciously validated. But it’s also disconcerting. Gender dysphoria can untether me from my body, leaving my sense of self adrift somewhere outside my physique. The fact that I most often find my gender represented among the space oddities and post-humans of galaxies far, far away is further dislocating.

For me, being a TCK meant hanging off a ledge with my feet flailing in space, utterly ungrounded and desperate for solidity. Durrell, Bowen, Ondaatje, and others put a ladder under me. Each scene that depicted what it is to love a place, every landscape that was instantiated via metaphors of the body, any character who struggled with their national or cultural identity, was one rung closer to the ground. These books – so vividly, solidly situated in Corfu, Ireland, the Sahara – became the passage to feeling my own feet on the ground in Czech, Nova Scotia, Singapore, Arizona, and so on.

Gender-creative science fiction, by contrast, gives me a starship to transcend dominant social structures. It teleports me into myriad experiences and embodiments of gender. But what happens once I’m out there, out beyond Kuiper Belt of gender hegemony? Unlike other formative books in my life, these ones don’t leave me feeling more present in my own skin or more physically connected to the world around me.

Living outside gender norms brings regular jabs of derealization, little moments that jolt me out of my body. Sometimes it’s the ever-present M/F checkboxes. Or, the scene that recurred at malls and train stations when I was a preteen in France: a bathroom attendant took the one Euro fee and tried to shunt me into the men’s room while my mom tried to convince them I was a girl, and I stood there voiceless because I didn’t speak French yet. More recently, it was the boss who ruled that putting preferred pronouns in staff email signatures – a common practice in our field – would happen “over my dead body”. And there’s the fact that people close to me still usually call me “she”, and I let them, because to insist on a truer “they” would feel too needy and too exposing. I’ve always been prone to believing that my experience doesn’t matter and my needs aren’t valid, and moments like this can feel like proof that, indeed, I am asking for too much to hope that being nonbinary could be an accepted, even unremarkable, option in life.

Of course, there are much worse things than these little digs. There are people who are killed for their gender nonconformity, 331 documented in 2019, many of whom were transwomen of colour, according to the Transrespect vs. Transphobia Worldwide research project. Yet the daily jabs are breadcrumbs on the same path that leads to violence. The structures of our world – legal and medical systems, immigration and employment processes, access to privacy and safety, and so on – are built with an assumption that gender is binary and fixed. To be outside the assigned-at-birth categories used by most governments is, as trans theorists tell us, to risk one’s standing as a full citizen. Those without accurate IDs, without easily categorizable bodies, without accepted ways of living their gender, become less real in the eyes of others and the state, and less deserving of human rights.

Feminist and gender-expansive sci fi widens the realm of discourse, a hyperspace bypass carving new routes for representation and critique. These writings take us to such an important place. But it’s not a place where I can feel my feet on the ground. The fact that gender nonconforming characters are so often granted homes and full rights only in fantasy worlds becomes yet another jab. Anti-trans activists further twist the situation when they use rhetoric like “fantasy” or “magical” to dismiss trans and nonbinary experiences. I know there are books that place gender nonconforming people in real-life settings, but they aren’t exactly plentiful. Where gender is concerned, it’s still too easy to consign the outliers to alternate realities. Those of us who transit gender borders also need to see ourselves walking through fictional fields set in real countries and sailing through pages that give us homes on this planet instead of some other.

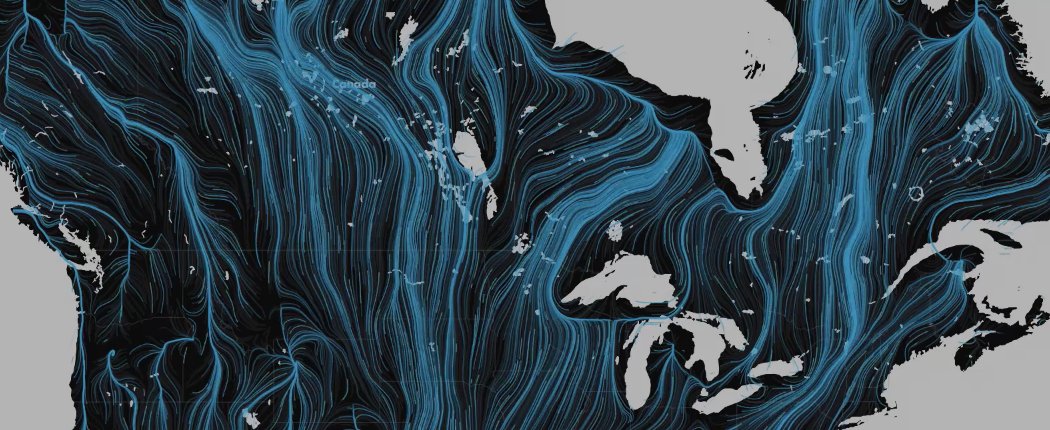

Cover image: still from an animated map by Dan Majke for Audubon, depicting the projected major paths some species of birds will take to reach cooler climates in the next 70 years.

This is part of ROOT MAPPING, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring which maps might help us live with a clear sense of where we are. ROOT MAPPING is conceived and edited by Melanie Viets.