*** Rhythm is currently closed for submissions. We will reopen again soon. You can sign up to our newsletter for updates. ***

From the impact of clocks on notions of time, to the effects of computers, trains and planes on experiences of modern life, rhythm – in various forms and ways – determines, and has always determined, how we live our lives and how we see the world. Some rhythms bring people together: listening to music can be a collective experience; morning commutes and long journeys can create a shared rhythm amongst the travelling bodies.

Rhythm in poetry dictates how we digest words and phrases, and often is what makes lines memorable and powerful. Take Thomas Hardy’s “Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me” , for example, or Maya Angelou’s “But still, like dust, I’ll rise” . Hardy’s repetition of “call to me” heightens the sense of the speaker’s desperate anguish, and the repeated stress on “call”, before the dwindling dum-dum, “to me… to me”, highlights both the hopefulness and hopelessness of his hallucination. Angelou’s commas slow down the reader’s processing of the line and instil a quiet strength, power and dignity to the defiant statement.

Ancient rhythms of birdsong and seasons have increasingly been supplanted by modern rhythms of tapping, typing, scrolling, swiping.

Other rhythms, however, are less easily identifiable. Rhythm can be social or political. (And in Angelou’s writing, the personal and political are often inevitably entangled.) Breaking a rhythm can mean breaking – or breaking away from – an existing temporality or understanding of how we operate in the world. Rhythm can equally be gendered; motherhood and menstruation can affect our experiences of time. Forms of rhythm can also vary geographically and ecologically, as from city to countryside, and can change over time. Ancient rhythms of birdsong and seasons have increasingly been supplanted by modern rhythms of tapping, typing, scrolling, swiping. Even linguistic and physical rhythms, how we communicate and move, though similar within proximate communities, vary infinitely worldwide.

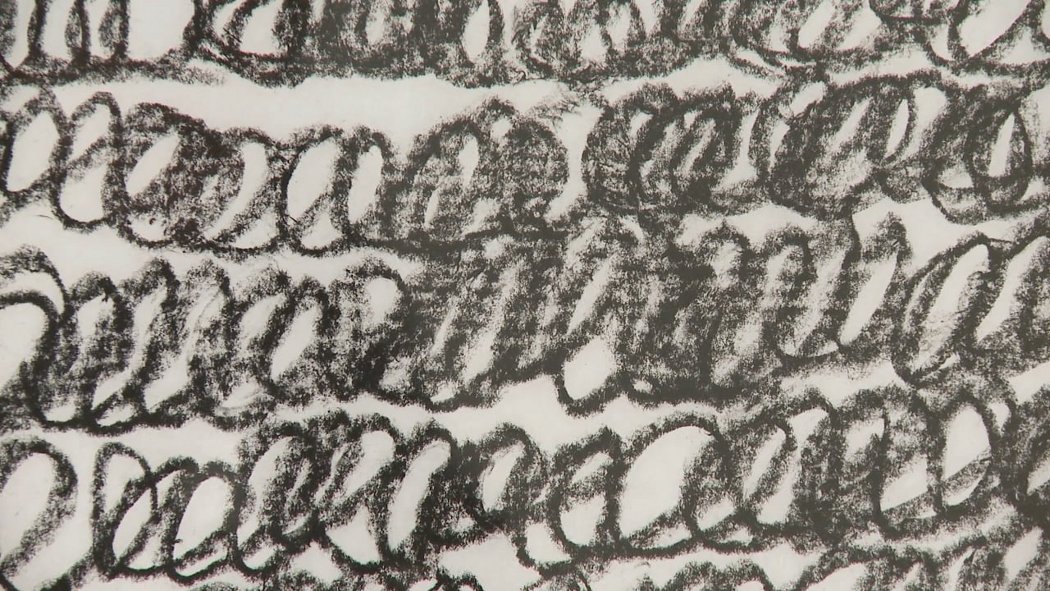

This section seeks to explore how we sense and interpret rhythm today, and to understand how it can be both a collective and an individual experience. We are just as interested in explorations and considerations of rhythm as a feature and product of art, as we are of rhythm as a component of the artistic process. “I never violate an inner rhythm,” said Lee Krasner, for example. “I listen to it and stay with it.”

We welcome and invite a broad range of interpretations of and responses to ‘rhythm’ which might address or consider linguistic, physiological, social, cultural, urban, animalistic or musical rhythms, Rhythms heard or felt, seen or unseen.

We want to amplify the voices of people who are underrepresented in the fields of art and arts publishing – in particular, Black people, people of colour, people on low incomes, and those who self-identify as disabled, LGBTQI+ and/or working class.

Details

Please send all work to The Learned Pig’s editor Tom Jeffreys (tom@thelearnedpig.org), who will forward it to the editor responsible for this section, Rachel Goldblatt.

There is no word limit for written submissions. Please send as Word documents, not PDFs. For art and/or photography, please send no more than eight JPEGs, with a combined total no bigger than 3MB. We will get back to you within six weeks.

Please note: The Learned Pig is very much a labour of love. Our only income is from donations and these do not cover the costs of running the site. This means that, as much as we might like to, we are unable to pay contributors (or anybody else for that matter).

Image credit: Pierrette Bloch, still from interview with Marc Donnadieu, 2018