Maria-Chiara Piccinelli is director of PiM.studio Architects in London. She is a strong believer in the importance of public spaces for a city to thrive, and in the crucial role nature plays within architecture. She began her career in Italy, and has since worked in Tokyo, Edinburgh and Paris with Kengo Kuma & Associates, and in Rotterdam for OMA/Rem Koolhaas. Maria-Chiara co-leads “Emerging Tools – designing, building and making in the 21st century”, one of London School of Architecture Think Tanks, and she is also Architecture Ambassador for the RIBA National Schools Programme.

Ahead of Maria-Chiara’s appearance at the Rewilding Forum at OmVed Gardens, London on 4th May, she spoke to Anna Souter about rewilding architecture and designing across boundaries.

Q: Perhaps you could start by introducing yourself and your practice?

Maria-Chiara Piccinelli: I’m Maria-Chiara, co-director of PiM.studio. We’re a small architectural practice based in London, founded three years ago. We’ve been very busy since then working on the new V&A in Dundee, a project we’ve delivered together with Kengo Kuma & Associates (who are based in Japan). We decided to start PiM.studio in order to be able to do our own research and work on more experimental projects.

Q: Your practice is innovative in that it tries to accommodate flora and fauna as well as human beings. How do you think the needs of other species can be accommodated into architecture?

MCP: Since the beginning of construction, architecture has been intended to protect humans against the environment – against nature, against weather. This anthropocentric view has driven human beings to try to build and control their own environment. In our practice, we have always tried to go beyond this.

We need to re-articulate the relationship between humans, other species and technologies. Architecture is about creating new relationships.

Of course, architecture is meant to protect human beings. But it can also do more, and have more than one goal. It’s important to us that we don’t start from the idea of separation: that inside is inside and outside is outside, and that architecture is the thing that separates them. We think of architecture as a less rigid element.

It can still be welcoming and comforting for humans, but it can offer these things to other species as well. This is a bit radical, maybe, but we believe we need to re-articulate the relationship between humans, other species and technologies. Architecture is about creating new relationships.

Q: How do you establish the best ways for a particular building to respond to its environment?

MCP: We’re mainly informed by the site and the location; it’s fundamental to visit the site. We like to understand as much as we can about the relationships between different species in the existing ecosystem where the project will be implemented. As architects, we often move quickly from one place to another, so it’s important to understand as much as possible about the environment in each location – the weather, for instance – because these elements have to inform your design.

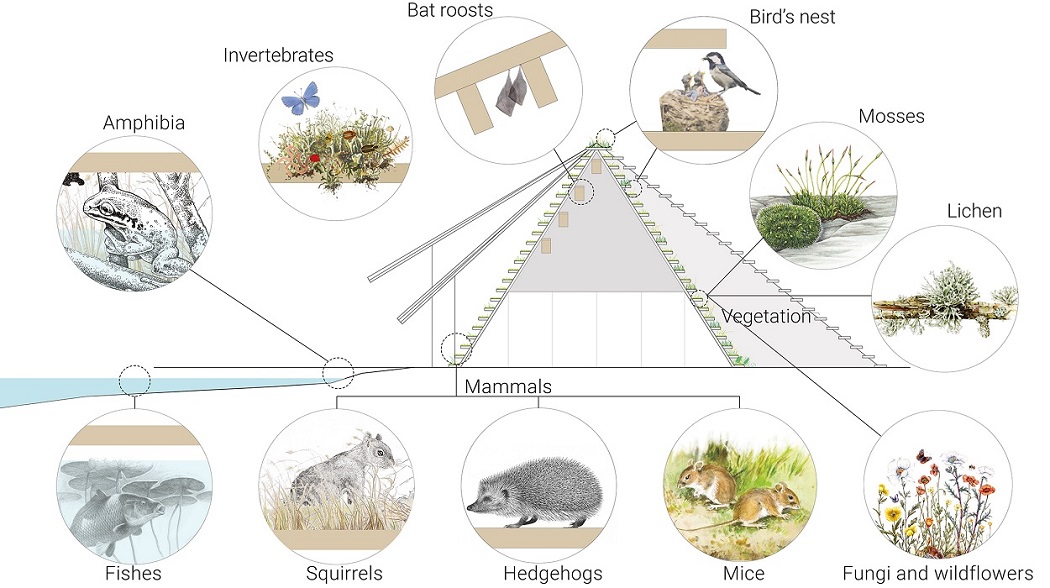

We want to plant the seed of introducing natural elements into architecture. For example, we’re working on a private house where we’ve been finding ways of incorporating local materials and the needs of other species. We’re using bricks that are made of soil from the site, connecting the building with the landscape. We’re also trying to raise the building off the ground slightly, to create a space under the house that will be a free environment for small animals and invertebrates to move around, so the house doesn’t act as a barrier.

Q: And is your research more theory-based or is it more hands-on, working onsite?

MCP: Definitely both. We always work with a lot of consultants as well, drawing on others’ knowledge of gardening or ecology or technology to complement our own understanding. It’s important to work as a team: I believe that the more diverse the team is, the better the project will be.

We often want to cling to control, but it’s foolish to think you can fully control the natural world.

One of the places where we used consultants’ knowledge a lot was in the V&A Dundee, where we were pushing to incorporate naturally ventilated public areas. It felt important to us since museums can sometimes feel closed off or disconnected from their setting, because there are security and conservation requirements for housing valuable collections. But by having naturally ventilated central spaces before the climate-controlled galleries, we could give a sense of integration between inside and outside.

I think the issue of control is a key element of the relationship between humans and nature. We often want to cling to control, but it’s foolish to think you can fully control the natural world. It’s an illusion.

Q: I wonder if there’s a parallel between a practice that is quite collaborative and the kind of buildings you’re producing, which are essentially intended to be collaborative across species boundaries too?

MCP: Yes, I think it is part of the same approach. Again, I think that insisting on separation is unproductive. We believe that architecture should be an ecosystem of its own – it should be able to live and breathe. And this can only happen through integration. From our point of view, this means designing architecture that is open and porous and offers new opportunities. Architecture should be for all, not just for human beings; and we need to acknowledge that the more variety we introduce, the better it is for us as well as for others.

In my opinion, architecture should not be simply neutral but a positive force. And I believe it’s important to take a holisitic approach. So it’s not just about technology, or creating low-energy, low-maintenance buildings; it’s also about beauty, and creating new relationships and harmony with the existing environment.

Q: From an architectural point of view, do you feel that the differentiation made between rural and urban spaces is too extreme?

MCP: Yes I think seeing the rural and the urban as opposites is too simplistic. I think it can be unhelpful to always think about opposition. Both the urban and the rural are fundamentally man-made – both spaces are very carefully controlled, especially somewhere like Britain.

It’s the spaces where different elements meet that are interesting, and architecture can help us to participate in those spaces. That’s why we believe in cohabitation and a wider approach to integrating nature and human spaces. We need to deliberately give up control in some places, and create dialogues rather than boundaries.

Q: What are the main challenges that you face in trying to create a more ecological or rewilded form of architecture?

MCP: New clients can be very wary of new ideas, especially if you’re trying to introduce an ‘unexpected’ element into the design. When people think about maintenance and taking care of their buildings, most people think that a building needs to remain the same throughout its lifespan. We try to incorporate elements and materials that allow the building to age naturally and beautifully.

People are afraid of the things they can’t control. We want to challenge this conception and create designs that you can’t completely control – and encourage people to accept that some things will change and evolve over time, without compromising on the safety or functionality of the building. We try to design a prototype for cohabitation between man and nature by expanding the subject of architecture to other forms of beings.

Maria-Chiara is speaking about rewilding architecture at the Rewilding Forum at OmVed Gardens, North London, on Saturday 4 May 2019. Book your tickets here.

The Rewilding Forum is part of Rewind/Rewild, an exhibition exploring the ecological implications of rewilding and the broader possibilities for rewilding human lives. OmVed Gardens, 1-7 May 2019. Curated by Anna Souter and Beatrice Searle.

Read Rewind/Rewild co-curator Anna Souter’s essay on Rewilding the Exhibition.