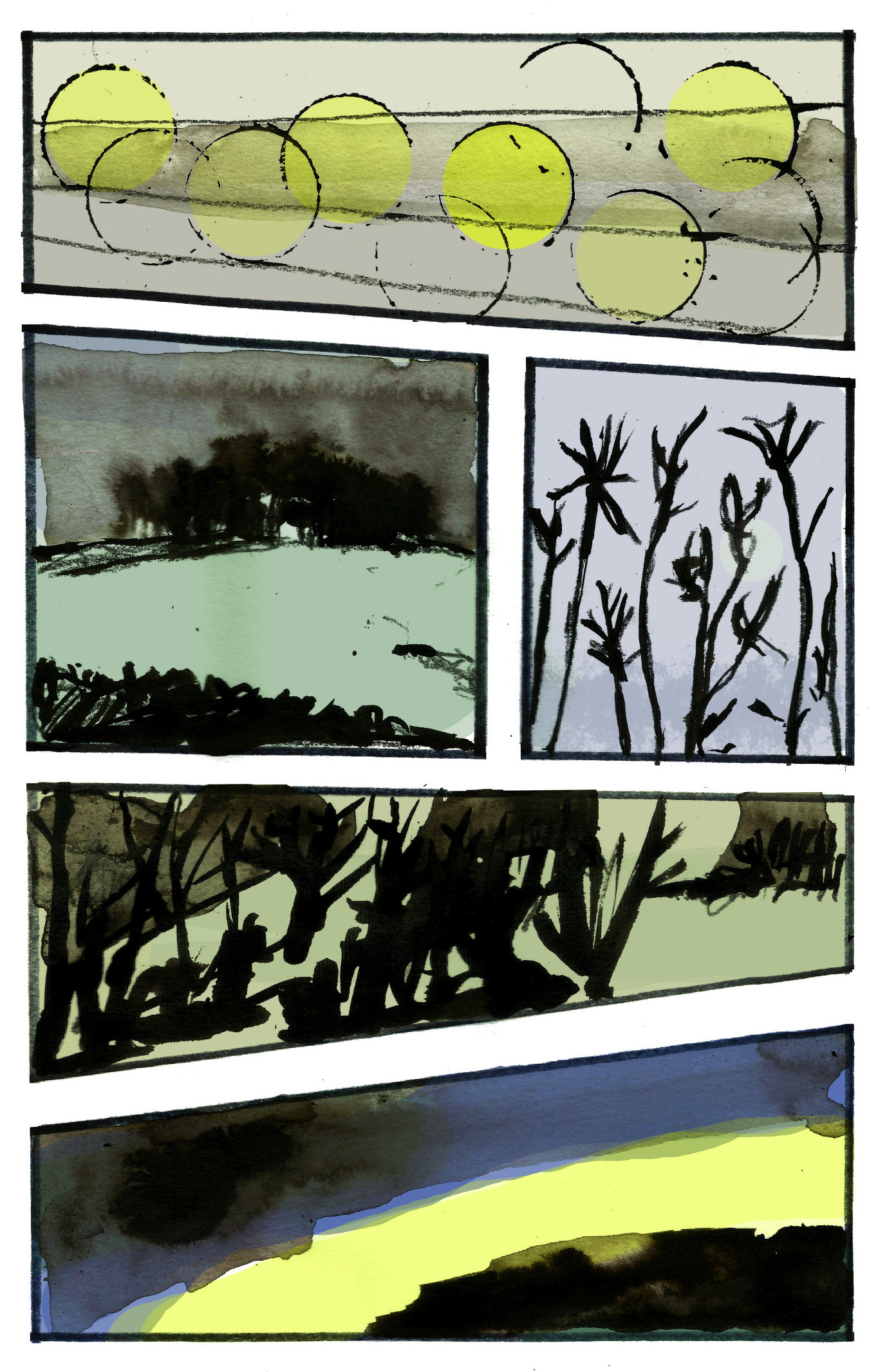

The art of Maxim Peter Griffin attunes itself to the spirit of a place. Or is it spirits? His work taps the frequencies that thrum, seldom heard, through the worlds we inhabit: not only the mundane technologies of contemporary existence (the overhead crackle of electricity cables, the whirr of the motorway, the view through the window panes) but also the half-buried imaginings of possible pasts: Mesolithic families, abandoned villages, witches, myths, Oliver Cromwell.

Maxim Peter Griffin’s is a strange, playful, stubborn kind of vision – in the best tradition of Stanley Spencer or Eric Ravilious. He animates landscape, brings pylons to life. His compositions are often sparse. They help us to focus on the essentials of texture or line: from the thick black delineation of a motorway to a horizontal scratch of barbed wire, a neat hexagon of hedgerows, or a scruffy smudge of roadside scrubland. Ridges, furrows, ploughed fields, hollow ways. “How long does it take to carve a hill?” he asks. Sometimes there are words in the landscape; sometimes you imagine you can read his lines, or between them.

I was lucky enough to work with Maxim on my own book, Signal Failure (Influx Press, 2017), to which he contributed maps for each chapter as well as a brilliant image for the cover. Now, Field Notes by Maxim Peter Griffin has just launched via Unbound. I emailed Maxim a few questions to find out a bit more about the project. Have a read and then pledge your support to make it happen!

Tom Jeffreys: You’ve mentioned that you produce work in response to Lincolnshire because that’s where you are – but what draws you to specific places there? What makes you want to record them / evoke them?

Maxim Peter Griffin: The Lincolnshire landscape is a tricky one – it’s quite hostile and very big – very widescreen and quite daunting – I like the edge of the North Sea, the coastal towns and the dunes full of pillboxes and medieval storm debris – history feels very close in these places. Space and time – the speed at which lives pass and hills grow and sea recedes.

As to why I record these places… I’ve got a funny sense of duty to what I am doing now – I must keep making these drawings until the answer presents itself.

TJ: These Field Notes feel rougher and more textured than some of your other works. Is this an evolution of your practice or a response to these specific places?

MPG: I think I’m less concerned with pleasing myself now – less fussy and more direct – I made a conscious decision at the end of October 2016 to draw wilder and it stuck. Everything feels more improvised and present – better that way I think – at least for the time being.

TJ: You speak about the “paperiness of paper” and I also think of some of your works as very physical in their creation and tactile in the results – yet I’ve only ever encountered them on the screen (or printed in my own book). Is it difficult to translate the materiality of individual drawings into digital form or a publishable book? Do some of your works translate better into book or digital form and others are best experienced in the flesh?

MPG: Paintings are always better in the flesh. I’d like to paint more but the mess and fumes are not practical – there are always children about – that and I can make drawings quicker than I can make a painting, there’s too much standing about and waiting with a painting – drawing in ink and pencil and water requires swiftness – Swiftness is good, energy is good. Once the drawing is made I don’t worry about them too much – I think that if this project with Unbound comes off, the resulting book will be as much of a surprise to me and everyone else – I’m quietly excited to see what will manifest.

TJ: In the accompanying video you talk about the “unfinished” nature of the drawings – hence the title Field Notes. Once funded and published though, the book will be a beautiful, finished object. Could you talk a little about that relationship between finished and unfinished? Why is it important to maintain a feeling of something unfinished in the final object?

MPG: I’m not sure anything is ever really finished.

TJ: The video also shows you out in the landscape while the accompanying texts are raw and note-like. How much of the art and writing is produced “in the field” and how much worked up or edited back at home in the studio?

MPG: All of the hard work happens outside, all the sweating and blisters and blood. I have to be able to look and get the wind in my ears – eat a bit of soup maybe. The drawings and words happen after as quick as possible – but at my desk in the dry and warm and where paper isn’t being blown about..

TJ: In the combination of text and image, what does the art do that words alone cannot? And vice-versa: what do the words contribute beyond the limits of the art?

MPG: The drawings are the cinematography and the words are the score. It’s all moving images.

TJ: How is it different working on a self-initiated project like this one compared to a commission like, say, Signal Failure?

MPG: Commissions are great. They keep one on one’s toes and always lead to unexpected places. They pay the bills! You meet new people! There’s a different kind of discipline.

Working on Field Notes is different – all kinds of things to worry about, all of those strange doubts – doubts in one’s quality, doubts in direction – Every day I have to step back and have a word with myself – keep myself disciplined, remind myself to look more and worry less – keep to the operation, keep drawing, keep the ink moving.

Field Notes by Maxim Peter Griffin will be published by Unbound. Pledge your support to make it happen!

www.maximpetergriffin.tumblr.com