Joanna Kirk and I are both artists living in Blackheath and have become good friends over time as our children are the same age, friends and at school together. This has led to frequent conversations with us sharing books (for example Karl Ove Knausgaard’s) and views on exhibitions and artists, on newspaper articles and TV documentaries. I’ve seen Joanna’s paintings develop over years and watched the run up to her current show at Blain Southern, often visiting her studio to see the work in progress. Even so, going to this exhibition was a revelation, and very moving. This interview took place a few days after the opening.

Victoria Rance: I was talking with a mutual friend about the time you were taking photographs in Shoreham Woods, which is where you told me that the image for Throne was from (and where you temporarily lost your youngest child Anders). It brought Samuel Palmer to mind, and I wondered how you compare your relationship and use of the landscape to his. He works on a much smaller scale but his work has a similar layering and intensity, and it also draws you closely in to another dream-like world. Do you relate to his work? What is the role of the landscape in your work? Does it personify particular moods or periods of your lifetime?

Joanna Kirk: My childhood was spent in the countryside and long summer holidays in Scotland when I just remember drawing, reading and walking. I remember being aware of the utter enormity of nature when young. We once went on a walk and I thought, “I will never see that particular stone again.” I was aware of our temporary existence on the planet and the vastness of mountains and landscape. I find landscape thrilling and at the same time terrifying.

I find landscape thrilling and at the same time terrifying. We are so informed by the myths we grew up on.

I was once walking with my young son and a friend with her two small boys. The children were running along in the woods adjacent to our path, and we had arranged to meet up at the end of the wood for a picnic. My friend and I were completely absorbed in our conversation and when we got to our meeting place her children turned up but mine did not. We waited and waited and still no sign of him. At this point I completely freaked out – probably irrationally. I had lost him, I would never see him again. The bad fairy tale had come true. It was such a primal thing; of course he was fine and turned up, but for a while it was just the worst thing. We are so informed by the myths we grew up on – the scary woods, the face in the trees.

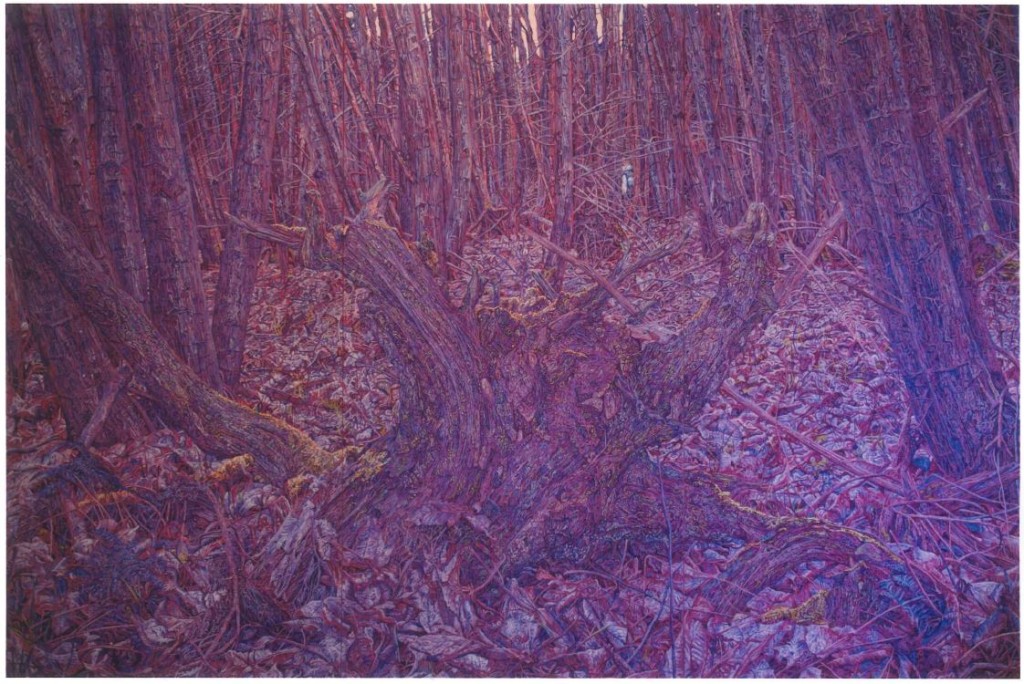

It was like being in one of my pictures. I felt, “It serves you right for doing this work.” I made a huge piece called Throne which is based on this day in Shoreham Woods. In the piece my son is peering through the wood and a stump is in the forefront, which is me. I am the ageing stump, the throne. I have since been looking at Palmer’s paintings of Shoreham with their sense of otherworldliness, but also the figures so connected to their environment. Sometimes the children are being protected by the landscape in my work and other times they are on their own. In Mothership I am the rock sending a beam of light onto my daughter to give her strength. All kinds of scenarios can be re-enacted in the landscape. It is the setting for a play.

VR: Yes I can see that. The intensity also seems to be heightened as I read the landscapes as internal – in relation to the body, as though they also describe the lungs, for example, or the alveoli, the brain, the womb. The feelings and sensations of breathlessness or anxiety are so strong that the landscape is doing more than just being out there; it is inside us too, and the viewer identifies with it viscerally. Is that something you try to develop? Is it conscious or just a result if your extreme identification with the subject over time as you work on the painting?

JK: It is conscious. In Self Portrait, the root is me and it looks like a living organ, with veins and arteries, pulsing with life at the heart of the tree. The colours are very bright and full of vivacity. It is about getting older and having still so much to offer – it is joyous but also witchy. The intense mark-making, which is built up layer by layer, adds to the feeling of anxiety. There is so much to look at on the surface that I think it feels alive. I work on every area of the piece so that it seems activated. The bright pinks and reds of the works evoke the insides of our bodies. I am trying to imply that the figures are on equal terms in the landscape, neither the figures nor nature is winning; it is the same.

There is a whirlwind of marks on each piece which adds to the feeling of movement. In I See You the boy is watching quite calmly this animate thing on the left. We don’t know if it’s a positive or negative energy but it is definitely alive, and deeply playful. We are in a gorgeous and unreal landscape, but it is about what is going on in my head.

We are in a gorgeous and unreal landscape, but it is about what is going on in my head.

VR: Yes, those reds and purples in Throne are very alive and disturbing. They help create the painting’s movement and energy. Of the blue paintings, Acceptance feels calm and the space receding rather than bursting out. While the stronger warmer blues in The Battle of Nant Y Coed create the feeling of both intense activity on the surface just near our eyes, while still allowing a sense of space further back.

Seeing the gallery full of so many immersive paintings using such different palettes brought home how strongly the palette changes with each work. I know you spend time staring into drawers at Cornelissen where you buy your pastels. Is this after you have decided on your palette or do those drawers help you make choices? At what point do you decide on the colours to create the mood and do you ever change your mind?

JK: I have a good idea on the colour before I start the piece. With The Battle of Nant y Coed I wanted the piece to be quite abstract from afar, but also moonlit. There is a real density of pastel in this piece so the blue is very strong. It is a chaotic but orchestrated piece and yet the all-over blue simplifies it.

With On A Headland Of Lava Beside You, made after a trip to Iceland, there is a very clean emerald sky and the lava field is teaming with colours, almost marine colours. It could be land or sea. In the piece Perfect World I use hot tropical colours to evoke a paradise where the children are cocooned. It is a Welsh landscape turned on its head. Sometimes I do change my mind during the piece. When I choose pastels I often look in the drawers and think, “I really must do a piece in those colours.” I don’t like to repeat myself and I love to be excited by the colour each time I start a new piece. Sometimes the colour I start with is eventually covered up: I might think I want to do a really bright red piece but then colour is layered over and over again and it becomes something quite different.

Pastel is pure pigment and from the earth, so it is a very immediate medium.

VR: I was also thinking about the pastels not just in terms of colour, but that they are made of chalk – the basis of which is the layers of shells of microscopic sea creatures formed over millions of years. You are using remnants of landscape to depict it as the cave painters did. But then I realised with a shock that of course we are made of the landscape too – the earth. Everything on this planet comes from it, but we humans have the most agency. We have become ambivalent: forgetting our primal relationship to the earth and actively destroying it.

Your paintings bring us back to a recognition of Mother Earth, the body we all emerge from – depictions of the tiny, tiny human on an amazing planet, as if we are seeing it or landing on it for the first time. Do you have any particular views or political beliefs on our relationship to the planet?

JK: Pastel is pure pigment and, as you say, from the earth, so it is a very immediate medium. Even though the sticks are quite small I break them and it is an incredibly messy material – it is powder. Depending on which piece I am doing my hands become that colour, so actually it feels like an ancient medium. I also work at home so while everyone is on their technology I am cave painting in another room. It feels strangely Neanderthal.

It is as though by using my children in the pieces I am seeing the landscape anew and for the first time. The world is both wonderful and also frightening. It is a way of looking at our primal fear of being alone in a vast world – we are at one with nature, but we have also become terribly complacent. Having children has meant I am looking on but also seeing the world through their eyes. I am frightened for their future but also optimistic. We are becoming more and more removed from nature in this chaotic world, and yet it is vital to have a connection to it and to show it respect.

Joanna Kirk is at Blain|Southern, London until 3rd October 2015.

Image credits (from top):

Joanna Kirk, On a Headland of Lava Beside You, 2014

Joanna Kirk, Throne, 2014

Joanna Kirk, The Battle of Nant y Coed, 2013

All images are © the artist and courtesy of the artist and Blain|Southern