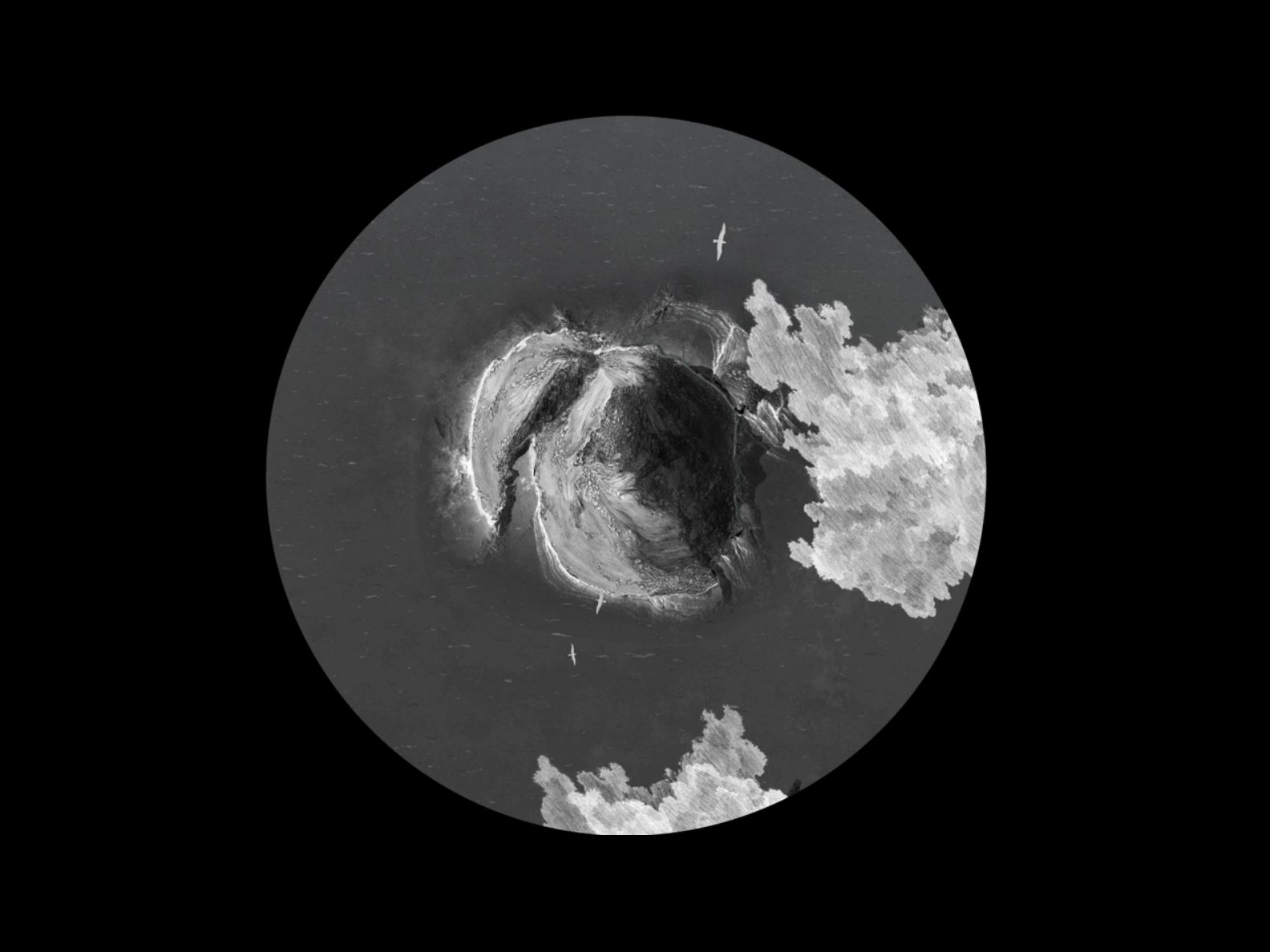

Spot-lit in the cavernous darkness, a model of a city. A model city: monotone, empty, pure, with the pristine edges of laser-cut steel glinting under light. It sits in the centre of an oil-black moat. The whole is perched waist-high on a slowly rotating table. Like many architectural models, the piece feels both large and small: we create in our minds the vastness of the thing depicted; we can hold in our hands that which is used to depict it. On the wall a real-time video camera re-presents the model of the city. The moat has become an ocean of black and white waves; birds fly across a clouded sky.

The installation, entitled Oikoumene (2012), is the work of Finnish art duo Patrik Söderlund and Visa Suonpää (better known as IC-98) and is currently on display as part of Sound | Image | Experience, a large-scale exhibition of interactive artworks taking place at Wäinö Aaltonen Museum of Art in Turku, on the southwest coast of Finland. It seems appropriate that such a piece should be here, for even to visit Turku for the day is to be confronted head-on by the multi-layered history of the city, and arguably the history of cities in general. The term “oikoumene” was used in ancient Greece to delineate the limits of the known and unknown worlds. For the 13th century settlers who founded Turku here at the mouth of the Aura River, it must have felt like founding a city right on that limit.

Söderlund and Suonpää live and work here in Turku and the city is often their starting point. “We always start by looking at a space,” Söderlund tells me over coffee: “its character or its context.” The two met at the University of Turku while majoring in cultural history and started working together in 1998. One of their first works – 1998’s The “Administration Building” – saw the duo install an information board to point out recent increases in surveillance and control in the university’s administration building. In 2008, they teamed up with Chicago-based collective Temporary Services for It is always like this, a series of movable sandwich board signs placed across the city.

A sense of place is clearly important, but IC-98’s is not the kind of work shackled by its reference points. 2011’s A View from the Other Side, for example, presented an alternative view of Turku’s Gyllich Stoa, a 19th century former fishmarket that stood vacant for a decade before being converted into restaurants and bars in the spring of 2011. The work has been shown in Turku, Helsinki, London and Buenos Aires.

IC-98’s rise in prominence has coincided with the deliberate decision to eschew the written word as much as possible.

As you might expect from artists of increasingly international stature – they are Finland’s representatives at this year’s Venice Biennale – their work is not confined to the locations that inform it. Part of this has to do with language. IC-98’s rise in prominence has coincided with the deliberate decision to eschew the written word as much as possible. This was quite a radical departure for a duo whose early work consisted largely of public interventions and beautifully produced, academically rigorous artists’ books.

For artists living and working in Finland, such works invariably require supplementary text to be in Finnish, Swedish and English. Not only does this present an aesthetic difficulty (as any graphic designer will know) but it also means that, as artists, IC-98 were being forced to express themselves in languages not their own. Given the Anglo-centric nature of the art world, this is a serious problem for artists who are not native English speakers – especially those whose work is highly conceptual. “When we moved to animation,” explains Söderlund, “we stopped producing text almost altogether. As far as possible, the work should say everything that is to be said.”

Since then, IC-98’s work has generally involved large-scale animations in black and white. Works such as Arkhipelagos (covered here on The Learned Pig by Camilla Nelson) Abendland (2013-14) and Theses on the Body Politic (2007 onwards) explore a diverse but coherent range of themes: architecture, public space, the history of the city and of civilisation, and how that relates to humanity’s place in the environment. Time is also crucial – personal, historical, geological. Each work is characterised by a rhythm of slow stateliness and a strong visual language that blends the hand-drawn with the computer-assisted.

To what extent is humanity – on the vast timescales explored by IC-98 – defined by our use of technology as prosthesis?

It’s a long, slow process. After discussing ideas, the pair make a preliminary collage to help them plan the work. Once they are satisfied, Suonpää starts to draw all the different elements. “That is always pencil on paper,” he says. That the finished works are always in black and white is therefore less a stylistic decision than it is a material consideration. But it does help to mark their work apart from the big-budget film industry: “We are not here to compete with Hollywood,” says Söderlund. “Within two years you can date certain CGI effects – certain filters or mapping – but with our work we hope there is a feeling of strange detachment. It’s realistic but still stylised.”

From here, the drawings are scanned and worked up in Photoshop and After Effects. At this point, the duo enlist the help of Markus Lepistö, an animator with whom they have worked for many years. This is when more fluid effects such as smoke, clouds and water are added. “We use quite a lot of techniques,” says Söderlund, “but it’s important not to get carried away. It’s about balance – ideally the viewer should not be aware of the technology involved.”

This seamless blending of the hand-drawn and the high-tech is, for me, an important aspect of IC-98’s work. The result questions at what point a tool becomes a technology. Is there a structural break between the pencil and the personal computer? To what extent is humanity – on the vast timescales explored by IC-98 – defined by our use of technology as prosthesis?

While Söderlund in particular is clearly obsessed by technology (he tells me about his Commodore Amiga 500, the revelation of HD, and the 5K display on his new iMac) IC-98 are adamant not to be classified as “new media” artists. “We don’t have an interest in digital culture as such,” says Söderlund. “Technology is just a tool for us; we use what works. The medium is not the message.”

On the day I visit Turku, a light and sound piece entitled Okeanos has been installed in the dome-topped tower of the city’s Vartiovuori Observatory as part of The Blue Planet, an exhibition exploring the relationship between humanity and the Earth and featuring works by the likes of Elina Juopperi, Antti Laitinen and Marko Lampisuo. IC-98 have blacked out the dome’s interior space, save for a single shaft of light that lands upon a scorpion, part of the stucco frieze around the base of the ceiling. Max Savikangas’s music tells of maritime loss as it swirls through the chill sea air.

Architects and designers have been collaborating for ages, but the classic art school education emphasises the individual artist.

This is IC-98’s first sound piece (most of their animations are eerily silent) and the first time they have worked with a composer. But collaborations, with poets or with other artists, have been an integral part of their practice from the beginning. “Collaborating with others comes naturally to me,” says Söderlund. “Architects and designers have been doing it for ages, but the classic art school education emphasises the individual artist. I didn’t go to art school and I’ve always taken it for granted.” As a teenager Söderlund produced computer demos with his friends, with different people doing the music or the coding while he focused on the graphics. Suonpää spent ten years as a solo artist before the two formed IC-98 but he too had regularly worked closely with other artists. “I always welcomed collaboration with other people,” he says. “That’s why it worked straight away,” adds Söderlund.

Collaboration between artists is not always so straight-forward. With increasing levels of interest in the issue of labour in contemporary art (Milica Tomic’s interrogation of the work of Rudolf Stingel is especially insightful here) IC-98’s approach is instructive. Part of this has to do with the drawing of lines. They are clear about the differences between their work with Lepistö, the animator, (“the result is exactly what we want, with no personal touches from anybody else”) and collaborations like that with Max Savikangas, where the other is given a significant level of creative freedom. “With poets or composers like Max, we want more input into the collaboration,” says Söderlund, “but it can be a difficult process.”

That is one important clash that is essential to our work. One of us reads only novels; the other only factual texts.

In the past, the pair have worried that they have been too restrictive when working with young, experimental Finnish poets. “We were coming up with the concept and presenting it to them,” says Söderlund.” I had a problem with that – as if we were making them function as technical writers. But they come from an avant-garde tradition that embraces the idea of creative restriction, so they were happy to work within the parameters that we set.”

But working with Savikangas pushed their parameters further. “For Okeanos,” Söderlund continues, “I had in my head perfectly how I thought the finished work should be. Max’s version was not at all like I had imagined – but you have to accept that he is an artist in his own right. Through multiple listens I’ve started only to see the positives and to gradually forget my original vision.”

IC-98 have now been working together for seventeen years and clearly their own interests have converged. “Our horizons are getting very close,” says Suonpää. But they still play different roles in the process. “We both share a love of romanticism,” says Söderlund, “but Visa [Suonpää] generally prefers cartography and the scientific tradition of depicting the world in images. It’s a simplification, but Visa is interested in documents and facts, and I’m interested in fiction. That is one important clash between us that is essential to our work. One of us reads only novels; the other only factual texts.”

IC-98 are Finland’s representatives at the 46th Venice Biennale, from 9th May to 22nd November 2015.

Sound | Image | Experience is at Wäinö Aaltonen Museum of Art, Turku until 1st March 2015.

Image credits, from top to bottom:

IC-98, still from Theses on the Body Politic (Colony), 2010

IC-98, It is Always Like This (with Temporary Services), 2008

IC-98, Theses on the Body Politic (In the Labyrinth), 2008

IC-98, still from A View from the Other Side, 2011

IC-98, Oikoumene (installation shot), 2012