Stumbling dim across the surface of the earth: humanity. Our legacy not culture or religion or science, but ruin. Our lasting traces that of footprints, not brain waves. Is this what makes us unique? A geological force in our own right? Certainly this is the view announced in 2012 at the 34th International Geological Congress in Brisbane. According to these and other academics, we have now entered a period of geological time known as the Anthropocene – an age where mankind is one of the most significant agents of change upon the earth’s ecosystems. In short, the impact of humanity upon the environment has outstripped our understanding of it.

At the same time as this seismic announcement, came, we’re told, a strange occurrence: the disappearance of an island. Two continents collide; the island of Nuuk disappears without trace. Might this event have been caused by anthropogenic climate change? Might it provide us with a clue to a better understanding of the Anthropocene? Is it a symptom or a cause? These are the questions which form the beginnings of Lost in Fathoms – the first UK solo show for Anaïs Tondeur, a collaboration with physicist Jean-Marc Chomaz, currently taking place at GV Art Gallery, London.

The exhibition’s unifying aesthetic thread is a series of some 24 small-scale black and white images that Tondeur describes, tellingly, as shadowgrams. Each piece begins with a combination of digital and analogue processes that incorporates drawing, collage and photography in order to create a negative. This is then exposed, Tondeur tells me, “as if it were a photograph”, adjusted digitally and then printed. (Note this “as if”, which opens up a hypothesis whose truth or productivity remains to be analysed). These various stages open up a space for “surprises and accidents”, says Tondeur: “I am collaborating with the medium itself”.

On the ground floor, the shadowgrams are employed to tell the brief history of humanity’s interaction with Nuuk: from a chance discovery in the early 18th century by French naval officer Paul Syrillin to its rediscovery in 1948 by “a Nordic nation”. Botanical, entomological and geological studies followed in the 1950s. We see the crisp mille-feuille of sedimentary rock in Tectonic fracture. In places, pin-prick clarity, in others all is just out of focus. Figures convene conveniently on the edge of a black sea; springy lichen wraps the rocks of a long gulley; a pair of men row through the shallows, grey and blurred, as a crease of sunlight cuts across the centre of the image.

Each image is tinged with that melancholy so characteristic of photography – a vain fixing of what once was, or might have been.

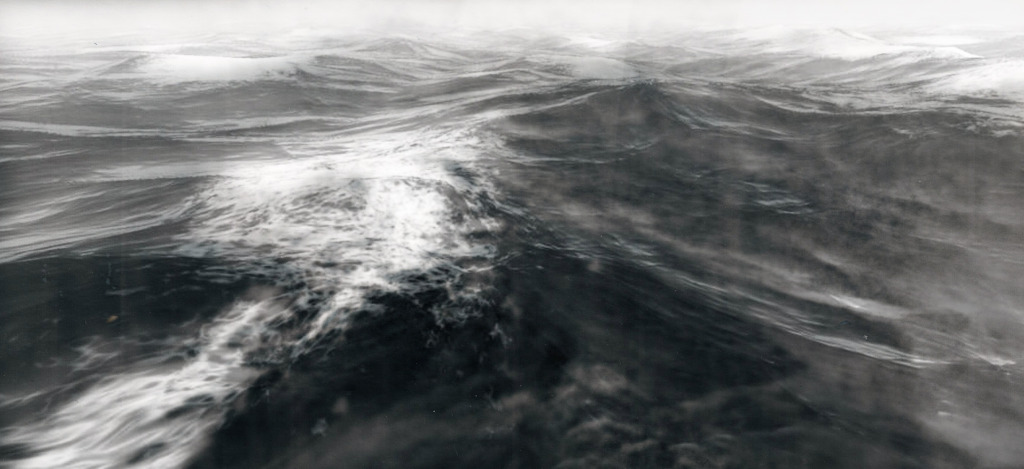

The shadowgram process enables the production of some entrancingly beautiful images. Each is tinged with that melancholy so characteristic of photography – a vain fixing of what once was, or might have been. Similar in format to the narrow landscape graphite drawings from Tondeur’s 2013 book I.55, the images here thrum with a rippling surface complexity. In places the effect reinforces the image depicted: two hooded figures repairing a buoy in a vast expanse of sea in Waterdive surface signature, for example. Here are shadows in the surface: waves crumple and foam, and the image with them.

Elsewhere, this effect frustrates the desire for straightforward legibility. Nuuk’s last transmission has the surface patina of a vintage NASA photograph and yet there’s something not quite right about it. The effect is reminiscent in some ways of Sophy Rickett’s Observation series, in that it’s unclear in places whether certain patterns are real phenomena depicted or side-effects of the image-making process. We know these are manipulated images, but we don’t yet know to what extent.

Looming large in the gallery’s ground floor window is an early twentieth-century military-industrial loudspeaker. Emanating quietly the rustling crisp-packet gunshot of splitting boulders – quiet (and somehow domesticated?) or impossibly large and distant. What is it doing here? Downstairs, as Tondeur and Chomaz’s collaborations extend across an international network of scientists and the exhibition diversifies accordingly, we’re given an answer. It is here that the breathtaking breadth of their work begins to become clear, as they attempt to explain the island’s disappearance through the apparatus of geology, first, and then oceanography. In the centre of the main space stands a rock upon a pedestal, a microphone dangles down above it, as if somehow the rock might speak to announce itself. As if? In truth, it already has: a red line of cable threads upwards from the microphone through the floor of the gallery to the loudspeaker above. This single rock – having been subjected to 80 °C and 1,000 atmospheres of pressure by Tondeur and Jérôme Fortin at the Geology Laboratory de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure – has been probed for certain secrets. Whether they have been revealed remains to be seen.

This single rock has been probed by science for certain secrets. Whether they have been revealed remains to be seen.

This striking image sets the scene for an array of approaches to scientific modelling. In the same room stands an echogram simulating the effects of earthquakes on a piece of basalt rock standing on a marble slab. On the wall is projected a slow-motion video depicting, at first appearance, the collapse into liquidity of a mountain of rocks. It’s actually another model: a 40-centremetre pile of salt whose properties Tondeur and Chomaz were exploring in a workshop with students. Behind a closed door, in a low-ceilinged nook controlled for temperature and humidity lies a wax oblong cut through by a central chasm formed by a process of cooling, crusting, and cracking. It’s lit by a bilious light like that of the Isotemp programmable power supply that stands nearby. The exhibition is the result of a residency at Hydrodynamics Laboratory of the École Polytechnique and Tondeur has worked closely with Chomaz at the National Centre for Scientific Research. “What I love about science is the freedom to play with scale and time,” says Tondeur. This much is becoming evident.

It is in the next room, however, that this playful approach to the apparatus of science reaches its peak. A huge half-tonne water tank stands in semi-darkness. Every minute or so, there sounds a bleep and a ball of water plummets downwards, swells and furrows outwards and gradually disappears into stillness. The water tank has been specially built to recreate the motions of a type of waterdive from a global oceanic circulation known as Thermohaline Circulation or Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC). Each circulation of this mass of water can take up to 1,000 years to complete. It is thought that these colossal loops play a key role in the regulation of the world’s temperatures. As the Arctic icecaps melt and release fresh water into the sea, there is a danger that the water density will no longer be sufficient to begin the circulation process. This is likely to have a significant impact on the climate, especially in Europe.

In such a state of constant flux, does the wave itself exist, as such? Really and truly out there?

Around the walls of the gallery are ocean samples collected from across the world: one set the result of Tondeur’s correspondence with a global community of oceanographers and now displayed in glass phials hand-blown by the artist, the other the personal collection of scientist Harry Bryden. One water sample comes from as deep as 8,900 metres, but each one has a story behind it, a network of connections. Between the two sets a map charts the progress of these huge circulation loops. I can’t help thinking of that old quotation attributed by Plato to Heraclitus: “Everything changes and nothing remains still … and … you cannot step into the same river twice.” In such a state of constant flux, does the wave itself exist, as such? Really and truly out there? Or is the wave more accurately understood as a model, a metaphor, or an “as if”? Here, in the gallery, it is experienced largely as traces – water is not a wave. Even the model cannot be viewed directly: like a star glimpsed out of the corner of one’s eye, the whole process is barely visible, and must instead be witnessed via its reflection, undulating across a wall of the gallery.

By this moment, it will have gradually dawned on the attentive viewer that the questions which profess to form the basis of Lost in Fathoms are, in fact, fictions. Nuuk never existed; it is a creation of the artist’s imagination. That is not to say it is a lie, however. Like a scientific model – as we have seen – this fiction creates an opportunity to explore the idea of the Anthropocene, the relationship between humanity and the world we inhabit. It is also an opportunity for more self-reflexive form of thinking – about the processes of science and the truths that the discipline is able to generate. Lost in Fathoms may be built upon a fiction, but Tondeur’s is not the tricksiness that seeks only to undermine the scientific quest for truth – or truth in general – by simply blurring the lines between fact and fiction; rather it demonstrates how fiction is often critical to our ability to access or create truth, and indeed may actually be a fundamental component of it.

Tondeur’s is not the tricksiness that seeks only to undermine the scientific quest for truth – or truth in general.

But it is also a comment on art too. Just as the exhibition revels in a making visible of the accoutrement of science – not only in terms of the physical paraphernalia but also in terms of the thinking and collaborative processes – so, likewise, Tondeur opens up her own artistic and research process. In a side-room off the main downstairs gallery spaces, the artist has recreated her own studio – replete with books and sketchpads, post-its, tripods, pencils and photos. Rock specimens from her various expeditions are pinned and wired to a wooden board. In the hands of other contemporary artists I could think of this would be the entire show. Here, it is but another gesture of confidence and clarity of vision. It brings the artist’s entire practice within the questioning framework of the exhibition, and in so doing moves deftly beyond the tired opposition between art and science. It is, in this context, a masterstroke.

Running throughout the exhibition is a critique of the time-honoured technique of empirical observation. Tondeur questions the limits of what we can see with our eyes. She reinforces the importance of a knowledge whose models and metaphors form a mode of technical prosthetics that supplement our engagement with the world around us. But she also, and at the same time, reframes this knowledge as something predicated upon a foundation of fictionality. The models, the metaphors, the grammar of a shadow on a wall, at the origin of an image: each its own “as if” which remakes a facet of the world afresh for discovery, and celebration.

Anaïs Tondeur – Lost in Fathoms is at GV Art Gallery, London until 29th November 2014.

Image credits, from top to bottom:

1. Anaïs Tondeur, Depth Sounders, 2014, mixed rayogram techniques, C-Print, 24x11cm

2. Anaïs Tondeur in collaboration with Jean-Marc Chomaz, Paul Syrillin, 2014, shadowgram 11x24cm,

3. Anaïs Tondeur, The ocean by Nuuk Island, 2014, mixed rayogram techniques, C-Print, 24x11cm

4. Anaïs Tondeur in collaboration with Jean-Marc Chomaz, Recording from the wandering plates, Lost in Fathoms (installation image)

5. Anaïs Tondeur in collaboration with JM Chomaz MOC Waterdive, Lost in Fathoms (installation image)

All images courtesy of the artist and GV Art Gallery, London